Jim Shaw

Jim Shaw: The End Is Here

(7 October 2015–10 January 2016), the first New York survey show of Los Angeles-based artist Jim Shaw’s work, reads like a cabinet of curiosities as much as it does an exhibition. Taking up three floors of the New Museum, the show consists not only of paintings, sculptures, videos, drawings and installations by Shaw, but also extensive collections of both thrift store paintings and religious ephemera he has collected over the years. The sense one gets is that the curators—Artistic Director Massimiliano Gioni and Kraus Family Curator Gary Carrion-Murayari—raided not only Shaw’s studio, but also his garage and attic in order to put together the exhibition.

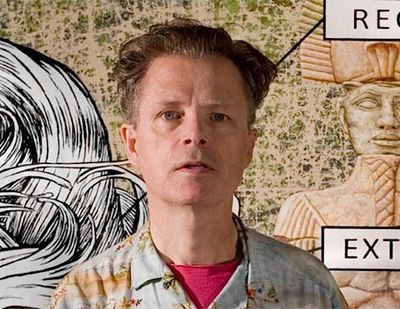

The show reveals not only the output, but also the influences and obsessions of an American artist who is finally getting his due in the art world. Born in 1952 in Michigan, Shaw moved to California in the 1970s to attend CalArts. He became part of a circle of artists that included Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy, all of whom were using a mixture of repressed traumas, pop culture and childhood memories to create work that was equal parts blasphemous, hilarious, shameful and nostalgic. The sort of work they made was given the term 'abject' by critics.

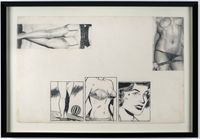

Shaw’s work is technically superlative, marked by a mastery over drawing especially. The exhibition includes examples from all of his most iconic projects, including My Mirage (1985–91), a collection of 170 objects that tell the story of Billy, a white middle-class male navigating American life in the 1960s and 70s; Dream Drawings (1992–99), which are pencil on paper drawings that show surreal, often sexual scenes laid out like comic book strips, and intricately rendered; Dream Objects (1994–present), which consist of paperback covers for books that look as though they were written by Edgar Allan Poe on acid; and Labyrinth: I Dreamt I was Taller than Jonathan Borofsky (2009), a large scale, immersive installation of paintings and theatrical backdrops that could be a Hollywood set for a movie in which the characters in Picasso’s Guernica join a circus that consists of religious freaks, hobos, travelling salesmen and people for whom the American dream has failed miserably. These are joined by an entire room of thrift store paintings, which are amateur works that show couples embracing, still lifes, and the interiors of houses. Another gallery houses The Hidden World, a collection of religious and pedagogical materials including kitschy oil paintings of scenes from the Bible, tarps decrying false prophets, cult manuals and other sorts of detritus produced by some of America’s most bizarre fringe religions. In an adjacent gallery plays The Whole: A Study in Oist Integrated Movement (2009), a video that shows women in sequined shifts dancing around a fake tree covered in shimmering streamers. It is an example of one of the rituals Shaw created for Oism, a religion he himself invented to make fun of people who take invented religions—which is arguably all religions—very seriously.

In the show, Shaw actualises what could be perceived as an adolescent-like, sex and cult obsessed imagination in his artwork. We sat down with Shaw at the New Museum on the day the show opened. Another survey of his work, Entertaining Doubts, will be open at MASS MoCA through 31 January, 2016.

How does a series or project start? Do you see an object somewhere that inspires you? In essence, what is your process?

When I did My Mirage, I was mining my own history and my friends’ histories from the 60s—I did a lot of research for it, but a lot of it came out of that. And, that was followed by the [Dream Drawings]. I started having dreams that were pretty interesting, had interesting artworks in them, so that’s why I started drawing my dreams, because I was going to make the artworks. So that’s how that dream-oriented stuff started. I’ve figured out that the core of dream logic is that it’s an occult way of telling you something by not just lecturing you directly, but by showing you in a satirical way or a symbolic way with things that are formally similar but not exactly the same. You know, the cigar that is not a cigar, and the cigar that is a cigar depending.

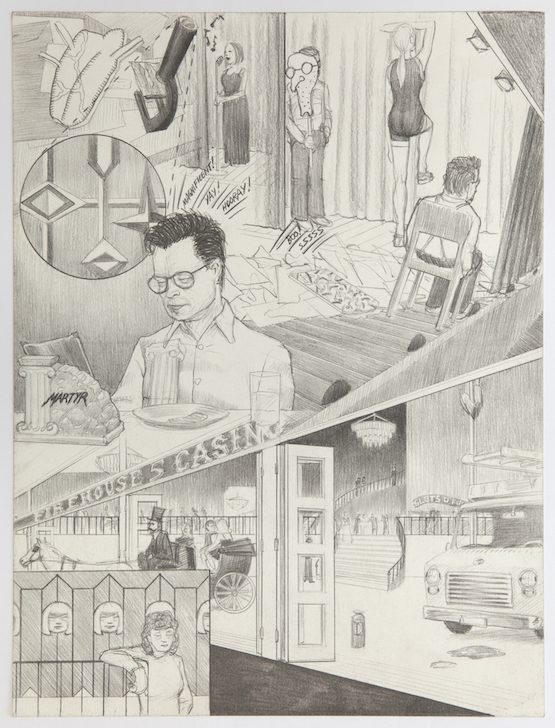

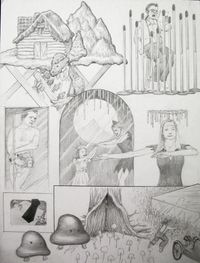

Jim Shaw, Dream Drawing ("We were sharing a house with Jody Zellen...") (1995). Pencil on paper. 30.5 x 22.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

I always find that when I try to write down my dreams, I come to a dead end. The logic of the dream makes sense until I put it down on paper. Then it falls apart. What is your process for transcribing your dreams?

I gave up trying to write them down because a lot of times they’re in the middle of the night and you can’t possibly read what you wrote, or you don’t want to turn on the light. Also, the process of remembering the dream verbally or in written form can erase elements of the dream, so I started recording them into a tape recorder and later transcribing them from there. But if too much time passes … the thing that you remembered when you woke up visually might disappear. In terms of being motivated to begin them [the drawings], if I’ve got a goal to produce a show, some idea might come up that I might normally put on the back burner but if it’s easy enough to get done, and it makes sense with everything else in the show, I’ll go ahead and I’ll do it without thinking about it for six months, and hopefully those aren’t bad pieces.

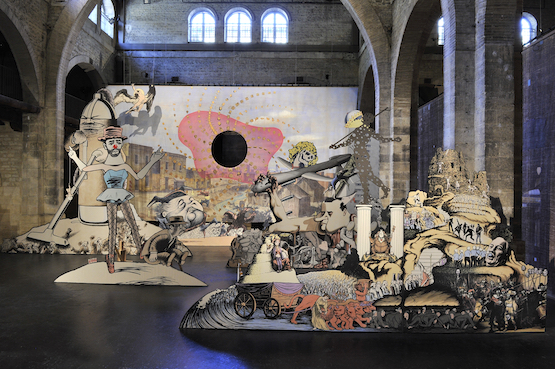

Exhibition view: Jim Shaw: The End Is Here, New Museum, New York (7 October 2015–10 January 2016). Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson, EPW Studio.

You adeptly work with so many different mediums–collage, watercolour, oil paint. How do you decide which materials to use on any given piece?

Well, like with My Mirage, I’d say, oh well this one takes place in the water, so I’ll do this as a watercolour. Or for example I wanted to do something in the style of this 60s woodblock printer, so I did a piece that involved puppets and wood and cutting wood. So sometimes there is a root aspect to the medium. But others are practical. Like if you’re doing a giant banner on a backdrop, then oil paints aren’t going to work. If you’ve got something that you want to turn around quickly, I use acrylic … my two favourite paint methodologies are gouache or oil. Before acrylics existed, gouache is what illustrators who were on deadline would use. You can get a lot more precise with little tiny details with gouache than you can in oils, because the brushes don’t, they just kind of get droopy with oils. Pencil used to be my favourite but then I started getting pains in my arm from using them.

You’ve been in Los Angeles since the 1970s when you graduated from CalArts. Why did you stay?

Well I forgot to move. I think if you were an ambitious artist in 1976 maybe you would have moved to New York, I mean, our friends Tony Oursler and John Miller moved back there, but since we weren’t from there we didn’t feel obliged. The art world was basically dead in the water when we got out of college so it didn’t much matter that you were in LA because what were you going to get out of being in New York? And I sort of fell into working in the special effects world. Other people might have fallen into doing set décor, or, there are a lot of different art-related jobs, now there are even more. Now our neighbourhood is just chock-full of people, I don’t know how they can afford a house because it’s so expensive now, it used to be cheap.

Exhibition view: Jim Shaw: The End Is Here, New Museum, New York (7 October 2015–10 January 2016). Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson, EPW Studio.

What neighbourhood are you in?

In Eagle Rock, Highland Park. The prices are crazy—$700, 000 for a two-bedroom house. Who’s got that kind of money? But it used to be so cheap there, in comparison to New York. And you got more space. On the down side, just having to drive everywhere makes you kind of dumber, because you can’t read on the freeway.

Do you find the city of Los Angeles itself infects your work?

Having worked in the special effects business infected it.

Your work has so many elements of science fiction in it. What else influences you?

Well I hardly ever read fiction. For a little while I made some time to read Philip K. Dick. Everybody said how great he was, and he’s pretty good, although he’s got an ADD thing, where the first half of the novel is written while the drugs are kicking in, and then it kind of falls apart as it continues. And when I first moved to Los Angeles I started out reading a lot of Burroughs, and then I started reading like James M. Cain and Chandler, you know, the Noir. But mostly I read history and research. I read a lot of religious history, I’m always looking for weird mythological or religious stories, and also I’ve been reading a lot about slavery and Jim Crow. One thing leads to another, and I just happen to be in a bookstore and there’s something there. From the time my daughter entered first grade when she was six, until about a couple of years ago, we had no TV in the house because she would just, her eyes would just be glued to Hannah Montana, and so we realised that that was not going to be a good thing, especially because she goes to a school that forbids TV-watching, so we just got rid of the TV and there was plenty of time to read, just like in the old days. Though, I’m a very slow reader, and I only remember maybe a quarter of all the interesting things. I don’t have a mind like a steel trap, I have one like a colander.

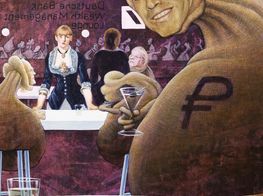

Jim Shaw, The Jefferson Memorial (2013). Acrylic on muslin with acrylic on muslin cut-out, hot glue, and fishing line. 365.8 x 670.6 cm. Courtesy Metro Pictures, New York, and Simon Lee Gallery, London. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg.

Where did your initial interest in fringe religions start? Were you raised religiously?

Episcopalian, which is kind of neither here nor there. I was always jealous of my Catholic friends because of all the weird stuff they would talk about that had been drummed into their heads. Then I started researching the Puritan history of America while I was working on My Mirage and I gained more interest in those things. Then self-made religions interested me, like Dr. Jaggers and Miss Velma, or Richard Shaver. I just thought it was intriguing that people could decide 'Well this is a whole new Bible' and then create a following. And suddenly there would be this whole new thing like Mormonism or Scientology.

What do you think is the key to getting other people to follow a new religion?

Well I think it’s a schizophrenia with the inborn DMT that’s in your brain that would make a tree talk to you, and then of course a lot of people have no followers, they probably don’t have that drive to have sex with underage people in their flock or whatever it is that seems to happen with cults. Control of sex is important. Even when they’re not having any sex, like in Heaven’s Gate or whatever, when they’re chopping their genitals off, it’s still the control of sex. The leader would dictate that you were now going to be the sex partner of someone else, it wasn’t like you were having orgies, it was sort of a restricted sort of free love.

Jim Shaw, Labyrinth: I Dreamt I was Taller than Jonathan Borofsky (2009). Acrylic on muslin canvas stretched over plywood panels. dimensions variable. Collection Eric Decelle, Brussels. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Praz-Delavallade, Paris. Photo © F. Deval, CAPC Musée d’art Contemporain de Bordeaux.

Is there a part of you that wants to be able to believe yourself?

Oh yeah, believing in stuff is great. That’s why conspiracy theory is really seductive. A lot of conspiracy’s effectiveness is based on saying 'Well this is the evidence, and the bullet couldn’t have done these things, but what if the evidence was just poorly collected?' Like with the JFK assassination, conspiracy theorists were like, oh the LAPD did a bad job of collecting evidence, but in the end, it really was just a guy with a gun.

Where did your impulse to collect the flea market paintings come from?

Well, I’m anal-retentive. I collected comic books as a kid, and Psychedelic San Francisco posters as a teenager, and records and books and so on. Paintings are a unique thing. They’re not mass-produced. Also not knowing much about the artwork made it fascinating because I could project onto it. Even with my own work, I like that people don’t know what all my work is about because it means they’re still projecting onto it. The stuff in the thrift store collection is a way of looking under the lid of America, the subconscious. But of course I’m ignoring 99 percent of what I see in thrift stores, and I also don’t pay much money for them because otherwise you’d become an addict to this stuff.

What kind of stuff are you addicted to now?

Religious propaganda on the Internet.

Why?

Because you can just click on it, it doesn’t take up much space, and there’s a lot of it. You’re in this rhizomatic realm, and you can go into all these different directions. You know, if you happen to watch this one anti-Masonic YouTube video, and it takes a bunch of time, and then there’s this other thing to watch. That’s my downfall. It could consume all your energy to do this well.

Exhibition view: Jim Shaw: The End Is Here, New Museum, New York (7 October 2015–10 January 2016). Courtesy New Museum. Photo: Maris Hutchinson, EPW Studio.

As a final question, are you happy to finally have a survey in New York?

Well, absolutely! I’ve had great shows in the past, but they’re often in relatively distant locations. This is the first time I’ve had a great show that’s in a great metropolis. I’ve had shows in Bordeaux or Newcastle, and people loved seeing them, but not that many people get to these places. —[O]