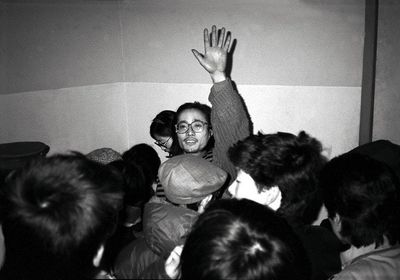

Johnson Chang

Johnson Chang. Courtesy Hanart TZ Gallery.

Johnson Chang. Courtesy Hanart TZ Gallery.

Johnson Chang, gallerist and curator, is a pioneer of the Hong Kong art scene. Through the establishment of Hanart TZ Gallery in 1983, Chang created a platform for new art from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, redefining the market with his organisation of China's New Art, Post-1989, held at the Hong Kong Arts Centre in 1993.

Over 200 works by avantgarde Chinese artists—a third of which Chang had to purchase in order to take them out of the country—were arranged into six sections: 'Political Pop Art', 'Cynical Realism', 'Post-Idealism', 'Emotional Bondage', 'Rituals and Purgation', and 'Introspection and the Retreat into Formalism', with a pared down version of the exhibition subsequently travelling to the Melbourne Arts Festival, the Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art, and further afield.

same year, four of the exhibition's Political Pop artists—Yu Youhan, Wang Guangyi, Li Shan, and Wang Ziwei—participated in the Venice Biennale, marking the first Chinese artists to do so. This exposure led to a 50 percent mark-up in prices of works attributed to the movement. And thus, Chang had created a niche.

Chang continues to invest in the dissemination, understanding, and appreciation of art from the region. He is a preservationist of Chinese culture who keeps one foot in the academic world as a guest professor at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou.

Intellectual rigour is visible in his curatorial practice, which is lined with a history of projects, including the Chinese Exhibition of the 1995 Venice Biennale; the China section of the 22nd International Biennial of São Paulo in 1994; A Strange Heaven: Chinese Contemporary Photography, at the Galerie Rudolfinum in Prague in 2003; and the Third Guangzhou Triennial in 2008, co-curated with Gao Shiming and Sarat Maharaj under the title Farewell to Post-colonialism.

Hanart TZ Gallery has held shows for some of Hong Kong's most respected artists, including Gaylord Chan, Chu Hing-Wah, Irene Chou, and Luis Chan, whose fantasy landscapes of the 1960s are currently on view at Shanghai's Power Station of Art until 23 June 2019.

Equal weight has been given to Taiwan, with names such as Ju Ming, Chen Tsai-tung, Yu Peng, and Yeh Shih-Chiang. Between 22 March and 4 May 2019, over 30 oil paintings by Yeh will be presented at the gallery in an exhibition titled Edge of Sea and Sky, following the late master's presentation at the gallery's booth at the inaugural Taipei Dangdai in January 2019.

In this conversation, Chang outlines the gallery's future projects, and discusses some of the key elements that define its programming.

TMCould you tell me about your work and influences after graduating from Williams College in 1973 that led you to the founding of Hanart TZ Gallery in 1983?

JCWell, I was always interested in painting, and in those days it wasn't really a respectable subject to study. I took classes when I was a high school student and subsequently lost interest, but I still had this fascination with the history of modern art and how it reflects modern thought; modern thinking.

When I was introduced to philosophy at university, I often would refer to works of art to illustrate ideas—that got me into the habit of using art to check abstract ideas. In those days, some of the great collectors who were from China were still around. I have a distant uncle who was a student of Wu Hufan, so he had a big collection of works by landscape artists and old photographs.

Ming and Qing painting was the norm, and after the Cultural Revolution there was a lot of art being thrown out as rubbish, so there was a time when a lot of great material changed hand.

So, a friend and I started a little shop that dealt in old master paintings, but then I got a little tired of that after a couple of years. I wasn't really working at this place, I was doing some other things.

At that time I was writing about art in Hong Kong and Taiwan, about Mak Ying Tung, Ju Ming ... I was very interested in art that was happening in Taiwan, because artists who were not trained in the art academies in the West took a very different approach to things, so I was interested in art of a different reference point.

TMThe opening of China's New Art, Post-1989 at the Hong Kong Arts Centre in 1993 had great influence on the market of contemporary Chinese art. Can you tell me about the before and after? Had you already established an audience or client base through the gallery?

JCNo, that collection was not very good on the market—I think we sold one or two pieces to David Tang and a few friends who helped me finance the show. The exhibition was originally planned for January 1992 and it would have happened in 92 because I started putting it together in 91, in fact I started working on it in 1990.

It was intended for the Hong Kong Arts Festival in 1992, but then, I can't remember why we couldn't do it—either it was because it was a bit rushed, or maybe it was because we must not have made the proposal early enough. In any case, Oscar Ho was a partner in Hong Kong who launched the show.

He was the head of Hong Kong Arts Centre. We postponed it to 93, because it was a show intended for the public platform, it was not destined for the gallery. And if we had opened it in 1992, we would not have had the works of Qiu Zhijie, because he only graduated at the end of that year [from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts], and we wouldn't have got his graduation work for the show.

TMIn 2013 you helped organise the first Confucian rites conference at Tsinghua University since 1949. Confucian values—particularly the concept of Li, a socialised modus operandi that works towards a balanced world order—are of key importance to you. I was wondering if you could please elaborate on how this feeds into your work?

JCI've had a long interest in Chinese classics, partly also starting from having missed it. Very few schools in Hong Kong were teaching it. I took one year off from university and I tried to learn classics at Hong Kong University, but I realised that they only taught general things about history, literature, and philosophy to first-year students, and not the original texts.

You were given these introductions and these theories, and it definitely was not the way these classics were taught in the old days.

I wanted to learn the way it was taught in premodern China, in order to establish a corporial link with the past, and an anchor for finding reference to the past and to the contemporary, but then the best teachers I got interested in were not teaching in the university system, because the best classicists do not have good English, and without English you cannot teach in the university system, which is very ironic.

The head of department at Chinese U, his teacher was one of my teachers, but his teacher could not teach in the university level, so I spent a year studying under two or three people outside of university.

After I had finished school, I continued these extra-curricular classes with some of these very old-fashioned classicists, but then I was not a very good student because at that time I was distracted by many things—there were many things I wanted to do, and sitting down over a boring old book was very difficult.

So it was always in the back of my mind, and I think I returned to these subjects rather late in my art career—they were actually at the forefront of my mind all the time, but I hadn't found a way back into the past.

Later, I realised that if art differs from other branches of learning—because it is about a play with form, either the inventiveness of form, or learning about the past through form—the most representative aesthetic form of Chinese civilisation is Li. Especially Li in terms of ritual and etiquette. So that's why I thought this was the best way to focus on this part of the classics, which is most remote from scholarship.

People might ask why it might be important to learn how to bow, or how to walk, but without this, you cannot really speak about the Chinese body, unless you speak about the theatrical body. So I thought this is a very important subject for Chinese contemporary art to rethink. It's also a very expedient way to bring the most obscure, but in fact the most visible part of the classics alive again.

Because in the old days it was about the visibility of the rituals and of the body—the performance of the body, the shaping of the human form and the social form—which communes with the social world and the natural world.

TMAs a concept rooted in tradition, I am curious as to how it aligns with your inclination towards radical artists. Wu Shanzhuan's conceptual practice, for instance, seems to embody the theatricality of which you speak, but also diverge from any notion of tradition. What can his art—or the showing of it—teach?

JCIf one talks about the performance of the body, Wu has only got—apart from the poses he has made—the paradises, the nude photographs of his wife, or some of the more overtly sexual performances, but these were actually made as still images.

The only performance art that he made was in the mid-1980s, and they were made to resemble some very specific rituals of the Cultural Revolution, which were the sessions of denunciation. The sessions of denunciation were a political tool for exterminating populations of the society that the government disagreed with, and also to bring people to line.

But then it involves a social ritual, not on the governmental scale, although it was pushed forward by the government. It was put in place as a public performance for everybody on a grassroots level in order to get rid of landlords, to strip the rich of their property ... So these denunciation sessions were particularly brutal and totally antithetical to Chinese practices, and in this sense I think Wu Shanzhuan probably has greater insight into what contemporary art is than most other people, because he saw that social forms were the most important and crucial thing that made China modern.

TMAnother concept of yours is the 'yellow box', developed during your time as guest professor at Hangzhou's China Academy of Fine Art. Could you please elaborate on what that is?

JCThe yellow box is part of my interest in re-thinking how to re-orient Chinese contemporary art. From a larger framework, it is about what makes art visible and what also shapes the way artists think of art, and how they make art in the site of the exhibition, and also the audience they speak to.

That is really one of the major transformations of art for most parts of the world, that you start to make things for the museum, you start to make things for Western art history, and you start to make things for a narrative for that particular context.

In Chinese art, because the literati tradition is such a strong and rich tradition that has been continuous, the contemporary or the modern context has made practice of traditional literati art difficult, because you cannot show it properly in the contemporary exhibition context.

So the yellow box is really about thinking about the site of display, and the mode of connoisseurship for literati art, but if you reverse it and take the original context of the literati and see how other types of contemporary art—international contemporary art—see how they work in that context, it presents a totally fresh perspective. So I'm using that approach to present contemporary artists.

TMIn your work, you also activate the role of cultural mediator—as seen in the exhibition and series of forums on contemporary Indian and Chinese art that you organised in Shanghai in 2010.

This inter-Asian exchange is also evident in your establishment of Asia Art Archive with Claire Hsu in 2000.

JCI certainly think the great new resource for Chinese and other intellectual Asian thoughts are inter-Asia, and especially China with India, because East Asia does have a lot of common roots. India still has the greatest repository of traditions, and the strongest contemporary intellectual circles.

And I think that is a resource for bringing alive the past, and also making a link that would make us think outside the context of the modern, because the modern really means dealing with the West, being a paradigm for the future that was proposed by the West.

Working with that has probably been one of the most transformative things for most non-Western civilisations. Yet, at a certain point, the West started looking for resources outside of itself.

TMHong Kong's art scene has acquired most of its crucial components over the last few years—art fairs, institutions, galleries, and education. Is there any aspect that you feel is still fundamentally lacking?

JCIf it's in terms of art fairs, what we need most are the buyers. But for the art ecology in Hong Kong we need to support more interesting critical thinking, and more intellectual engagement with art, and also bring art into the fabric of society in ways more than just collecting and exhibiting. There are now many experiments in Hong Kong by young artists.

I've seen very good shows, and I feel that we are really not that far away from the days when people say, 'Ah, this is recognisable Hong Kong art.' There are enough diverse practices with a distinct, local concern. Local concern not in the parochial sense, but that rise up from the ground, and some of these concerns are very global.

In a way, a lot of the concerns are more global than some of those in Greater China, because it is really about living in an ultra-modern—meaning accelerating—urban situation.

Hong Kong artists have a lot to say with regards to cultural life in an accelerated urban society, ecological issues, privacy and contemplation .... I've seen a lot of good Hong Kong art recently.

TMWhat will you be focusing your energy on this year?

JCThis year is the centenary of the May Fourth movement, the centenary of exile, so I have one project that I'm doing with a photo-based artist.

A Singaporean photographer called Sim Chi Yin who works with the memory of lost political ideals, because her grandfather was someone who was ignored by the family, because he was a Malay communist.

So, tracing through history, to bring back the history of forgotten ideals through her work is one project. I also want to bring back a new show for Liu Dahong, the artist who I recently gave a talk on in Cambridge. His effort is to turn Mao's era into a mythology for contemplation—a project that is still very real in many respects.—[O]