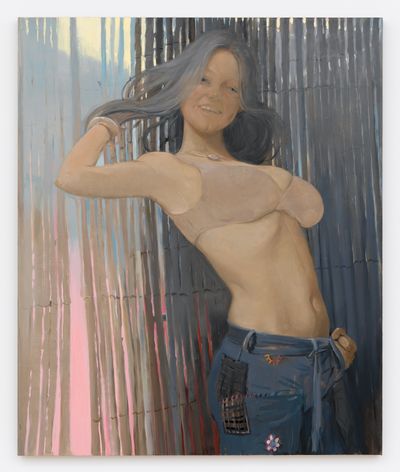

Lisa Yuskavage

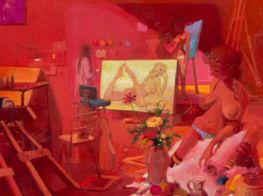

Lisa Yuskavage in her studio in Brooklyn, New York. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Jason Schmidt.

Lisa Yuskavage in her studio in Brooklyn, New York. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London. Photo: Jason Schmidt.

With a career spanning over 30 years, New York-based Lisa Yuskavage (b. 1962, Philadelphia) is a figurative painter minutely versed in the history of the medium, channelling artists from Francisco de Goya to Édouard Vuillard and Philip Guston in her ostensibly kitschy canvases.

Her paintings are immediately recognisable by their absurdly proportioned naked and semi-clad women, acid-bright landscapes, uncanny interiors and hippie figures that seem to have been cross-pollinated with religious icons.

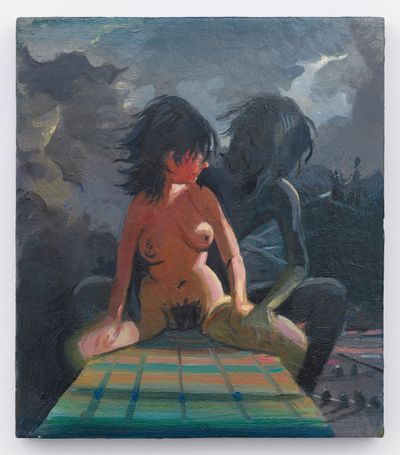

In addition to her figures' delight in their own fleshiness, there is an overpowering sense of otherworldliness at play. Yuskavage's paintings have been read as beguiling, disturbing and ironic, while the soft porn aesthetic—borrowed from men's magazines such as Penthouse—has in the past attracted criticism from some feminists. Regardless, she is reluctant to explain or justify the meaning of her work.

Growing up in the 60s and 70s in what was then a working-class area of Philadelphia, Yuskavage knew she wanted to be an artist early on. She earned her BFA at Tyler School of Art, Temple University in 1984 and later took her MFA at Yale. Her breakthrough came in the early 90s, after exhibiting a suite of modest canvases at Pamela Auchincloss Gallery she disliked so much she took a year off to reconsider her entire approach. The results were The Ones That Shouldn't: The Gifts (1991) and the 'The Ones That Don't Want To' series (1991–2). The earlier work shows a large-breasted young woman emerging from a rich green background with a sprig of flowers stuffed in her mouth and her arms pulled behind her back. 'The Ones That Don't Want To' paintings—which the artist also refers to as her 'Bad Babies'—are shockingly vibrant portraits of girls naked from the waist down, who appear to be merging with their pulsating backgrounds and stare (with the exception of one slightly more dreamy figure) disconcertingly at the viewer. Yuskavage famously channeled the persona of Dennis Hopper's sadomasochistic character Frank Booth from the film Blue Velvet (1986) at this point in her career, and her embodiment of a particularly extreme voyeuristic gaze lent the resulting works a startling vitality. Indeed, she has frequently cited cinema, from the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder to David Cronenberg's horror movie The Brood (1979), as an important force in her work. (The Brood was the title of her 25-year survey in 2015 at the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University [12 September–13 December 2015], which later traveled to Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis [15 January–3 April 2016].)

Yuskavage rose to prominence around the same time as other figurative painters such as Elizabeth Peyton and John Currin, who were similarly refreshing the genre with their own singular visions. In the 90s, she commanded solo shows in galleries in New York, Santa Monica, London and Milan, and her paintings were included in group surveys such as My Little Pretty: Images of Girls by Contemporary Women Artists at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 1997 and Young Americans 2: New American Art at the Saatchi Gallery in London in 1998. In 2000, she held an important solo in her hometown of Philadelphia, at the Institute of Contemporary Art. 'I confirmed for myself that she paints wonderfully, and that wonderful painting is what concerns her,' wrote Peter Schjeldahl in the New Yorker at the time.

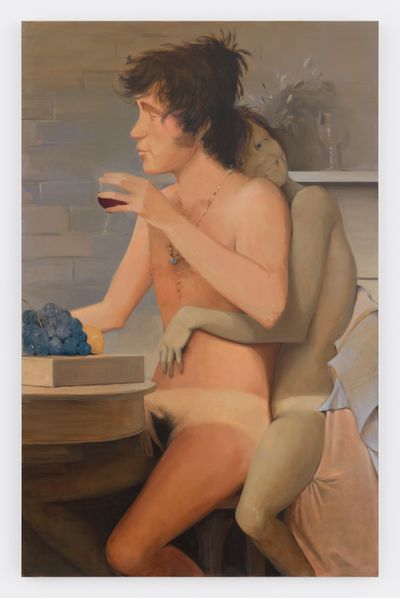

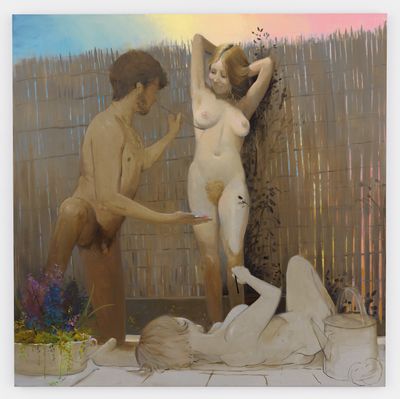

Yuskavage's latest show, which is on view at David Zwirner in London (7 June–28 July 2017), includes new works, most of them large-scale. Her female-centric images have in recent years begun to be infiltrated by male figures; in the show, variously spectral and vigorous males join the buxom women. She has also been treating the painting's ground with layers of taupe and leaving areas of the work unpainted—literally, nude. Where couples appear, their relations are signalled via the use of harmonising and contrasting colour combinations. The artist's typical melding of high and low culture is especially notable in Wine and Cheese (2017), a large canvas depicting a rosy male being embraced from behind by a bloodless-looking woman. Its references, the artist explained during a walkthrough of the exhibition shortly before it opened, include images by Hans Baldung Grien (1484–1545) but also one from Viva, the adult women's magazine launched by Penthouse founder Bob Guccione in 1973.

In this interview, Yuskavage discusses her interest in Renaissance modes of colour, contrast and harmony in roleplay, and why she believes it's important for figurative artists to study with abstract and conceptual practitioners.

LAI want to start with your more recent works, which increasingly feature male/female couples. What made you want to explore this dynamic after years of mostly painting female figures?

LYWell, every subject gets reflected in the formal material that you decide to work with. In the past, I had painted two females—in my world, I was not intending them to appear as lovers, but I was okay with people thinking that. The way that I was painting those figures was as if they were one thing, multiple characters emerging out of one person. Then I found an image of a couple sitting on a diving board, talking to each other, and the man was leaning around the woman. I started to draw from it and realised that I really liked it. It gave me this great opportunity to paint a formal diametric idea—this is a painting called Mardi Gras Honeymoon (2015)—where the female figure is rather luminous in pink and the male figure is in a grey-black world. He's a being of drawing and she's a being of light and colour. I like the way that there is a kind of parallel in the language that we use [around colour]. Like a red and a pink or an orange and a red are more harmonious, whereas a red and a green are contrasting. The idea of contrasting meaning different, clashing—it has a kind of emotional resonance. And that can be very interesting when applied to subjects like couples, because sometimes they're harmonious and sometimes they're clashing.

LAOne of your new works is The Art Students (2017), a painting of a man and a woman in the process of painting another female figure. The female doing the painting has yet to be filled out. You've talked in the past about your paintings as personifications, and I wondered to what extent are these works about the process of painting?

LYThat is the most recent painting, so I haven't had a long time to think about it. But I do think that if you compare [this work] to the smaller painting [Suburbs, (2017)], which is obviously a predecessor of that painting—but certainly not a study for it, because it's so different—this one became so much more like a personification. Like the painting is painting itself. It's in the process of becoming.

LAIn some of these paintings, there's almost a rainbow effect at work. Could you talk about your interest in cangiantismo, which as I understand it, was one of the four modes of colouring in the Renaissance?

LYWhat [these modes are] specifically made to do is show volume around a form. These are all very different, but the one that is the most queer, in a way the strangest, is this cangiantismo. That word, in Italian, as I came to understand it, just means to change colour. In the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo used a kind of cangiantismo in parts of the panels to show a miraculous happening, so that as you move round a form, it would go from orange to green as opposed to orange to darker orange, which is more naturalistic. Cangiantismo is the least naturalistic of all of them and it is more evocative of the supernatural. Let's say you have an Annunciation painting, where the Madonna's sitting in a very humble room, and then this angel shows up and the angel's wing is like a rainbow. That is a visual contrast that says something extraordinary has happened in the midst of this dull Earth. The idea that the world is ordinary and then you have these extraordinary occurrences... I've always been really smitten by that.

LAYou've been working as an artist now for around 30 years now. When did you know you wanted to pursue art?

LYSometimes I do believe in past lives, because as a kid, I had this weird understanding of what I needed to do and how I needed to get it. I knew I wanted to go to an art school and more importantly, I knew I needed to be around artists to live. I did well in some IQ test and was put in a programme where I ended up being taken out of school a couple of days a month, along with some other kids, to visit the Philadelphia Orchestra or the art museum. I remember seeing something like a Vincent van Gogh and thinking, that's my friend. I know him, I've met him before. I asked my mom if she would find a summer programme where I could go to a college. I took a summer class with college students and I had a wonderful teacher. I went back to school and took what I learned and worked on my own and went to the museum and drew from paintings. I always knew you should look at art to make art. I would stand in my bathroom and put a towel on my head like I was Rembrandt, with light coming down from a skylight, and do a charcoal drawing of myself. Then with that work that I did on my own, I got into college.

LAYou went to Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia and then did your MFA at Yale, where you studied with Mel Bochner.

LYMel, William Bailey, and a man named Jake Berthot—he's passed away. All of my teachers, aside from William Bailey, were abstract or conceptual artists, and I think that had a really profound effect on me. I think it's really important not to study with figurative painters if you're a figurative artist. In a way, somebody like Mel Bochner, even though his work has absolutely nothing to do with mine, was very strong on the lesson of: this painting, though it may be lovingly made, is an illustration. I find that one of the problems with contemporary figurative painting is that so much of it feels illustrational. It has interesting subjects but doesn't resonate the meaning, and I think that ultimately you have to have that in order for the painting to rise and be part of culture in a bigger way.

LAYou're especially drawn to the aesthetics of the 70s in your work: the buxom female figure, the clothing, the hairstyles. What appeals to you about that time period?

LYI guess at the time of my own coming of age, that's what people looked like. What impressed me as a young adult about that style is that it's about the desire for freedom. Sexual liberation, women's liberation—it's a perfect subject for me because ultimately my work is about freedom. People will sometimes expect me to be more of a political artist and I think that one of my staunchest political positions is that I'm not going to do that.

LAYou paint from imagination, though you have visual reference points, and you have also worked from life. There's one particular girl who seems to recur in new works, such as (Nude) Hippie (2016) and Hippie (Nude Bra) (2016). Where is she from?

LYShe's someone I found on the internet. It was a whole photoshoot, I think it took place in one day, all amateur. There's something about her—I really liked her personality and I really felt for her. I was a nude model at one time and had experienced some really awful treatment from people. I didn't pose for magazines, I was in school. I always imagine when I look at the pictures of these women what was really happening. What was it like in the room, who was taking your picture, what did they say to you, why are you making that funny face? And this is not something a man would necessarily do looking at these pictures. I don't know any man who paints the nude who was a woman posing as a model at one time. My own experiences feed my empathy.

LAEarly on in your career, you took on the viewpoint of the villain Frank [played by Dennis Hopper] in David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) to create a series of works. You've often spoken of your love of film. Do you find there's something either painterly about certain films or that your paintings are in some way filmic?

LYIt's often easier to roleplay than to be yourself, to imagine yourself as an 'other'. You can access different things. That crazy character that Dennis Hopper played in Blue Velvet—he terrified me but he also seemed a lot like a painting. The whole dynamic between him and Isabella Rossellini seemed like a potentially bad dynamic between a viewer and a painting, which is that he was violating her through his eyes. He wasn't touching her, she was just victimised by his gaze and that's very powerful. I really took that on because it was about the power of scopophilia. But it also relates to painting, the vulnerable painting hanging on the wall and the potentially cruel viewer. The specific painting I made from that was called The Gifts (1991), but after that the 'Babies' [The Ones That Don't Want To] series came. The difference was the babies started to fight back a bit. They were going to hurt the person as much as they were feeling hurt. So they were disappearing into this mist, but then they were also staring.

LAHow do you feel the critical reception to your work has changed since those early days, when people weren't quite sure what to make of it?

LYWell, I'm always ready for a fight [laughs]. It's still all over the board; there are still people who feel really offended. I think it's a good problem—a world-class problem—to have the jury still out because once you are consumed and become muzak, you are already dead. I think the world is essentially misogynistic and I think that's been borne out pretty well in the United States: we elected somebody who has admitted to being such a person and it didn't matter. [But] I think that there is such a thing as female potency. It's a very particular kind of intensity, a very particular kind of inner life, and I don't think it's been seen very much in history. To go back to harmonies and contrasts, if you are harmonious with everything that's come before you, you're doing nothing. If you create some dissonance... it's part of your job to make people see things they don't want to see. I do think that's part of my role, to carry on discussing my own brand of what it's like to be a female. [Though] I can't even really talk about what it's like to be a female, I only know what it's like to be Lisa. —[O]