Manuel Graf

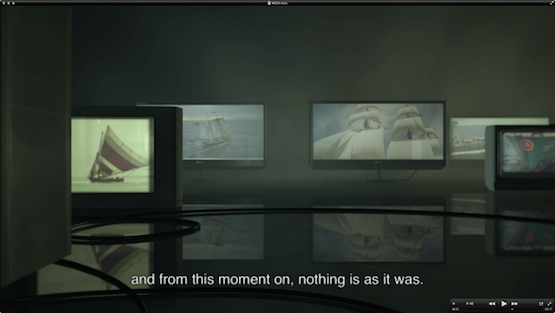

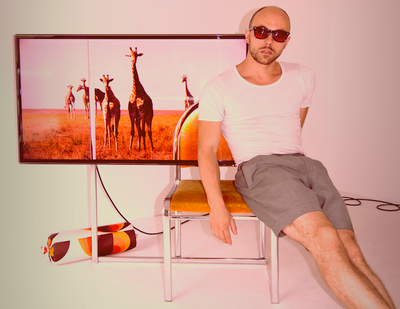

Manuel Graf. Image: Helga Meister

Manuel Graf. Image: Helga Meister

Manuel Graf is the winner of the Nam June Paik Newcomer Award, 2014: the International Media Art Award of the Arts Foundation of North Rhine-Westphalia (the Kunstiftung NRW), which has given Graf €15,000 for the realisation of a new work. Graf is a Düsseldorf-based artist who studied at the Arts Academy in Düsseldorf in the sculpture class of Magdalena Jetelova and Rita McBride.

The artist's practice is one that works with binaries, pushing for their inevitable destruction by forming bridges between such things as theory and practice. Working with diverse media, but often with a focus on short computer-animated videos, Graf considers questions that pertain to social theory: engaging with themes that are anchored to current affairs and current states of being.

SBHow did your 2005 exhibition curated by Pia Witzmann, Regarding Dusseldorf, at 701 E.V reflect on how your practice was developing, formally and conceptually? What works did you show?

MGThis was the exhibition in which I showed my first 3D-animations: Shulmantonioni from 2004 and 1000 Jahre sind ein Tag from 2005. From 2002 onwards, I was very often in Turkey where I saw Haluk Akakce's work for the first time. I was totally thrilled by his 3D-animations, which made me desperately want to learn this tool. So I used an old computer with 3D studio Max. The process was really one of learning by doing, since 3D-animation was not in the curriculum at the Düsseldorf Art Academy: I borrowed a manual from the public library and messed around instead!

For Shulmantonioni I wanted to produce stylish explosions in an environment that was based on Julius Shulman's iconic photographs of case study houses. Somehow, I managed to produce different kinds of fragmented and growing forms: designer chairs, firewalls, and stylish kitchens blow up like colorful mushrooms consisting of cubes and pyramids as you listen to Pink Floyd's score for Zabriskie Point. It's like the explosion scene from that, but from inside a house.

For 1000 jahre I basically made a technoid remix of Udo Jürgens' song 1000 jahre. The virtual camera flies through different scenes, or rather vignettes, which show formal analogies between historic buildings and their postmodern doppelgangers such as the Forum Romanum in front of a wallpaper-design by Michael Graves.

At the end of the animation, the camera flies through a shitty early nineties office complex in Düsseldorf, finally leaving this building and making a turn to look back at the simple 3D-models from behind. The work was a paraphrasing of, or an exercise on, questions of history, reprise and transience.

SBIn 2012, you staged These Romans Are Crazy! (ILS SONT FOUS SES ROMAINS!) at Hamburger Kunstverein, which was curated by Annette Hans. First of all: the title. Is this from Asterix?

MGYes, it's from Asterix, and in the series, this phrase is something Obelix keeps saying. In L'Odyssée d'Astérix, this phrase takes on a kind of twist. After a couple of days in the desert, Asterix and Obelix run into several warrior groups from historical Mesopotamian cultures—Sumerians, Assyrians, Medes and so on—who each greet the protagonists with a hail of arrows because they are mistaken for enemies.

Each time this happens, Obelix says that each culture is crazy—like "these Hittites are crazy!"—which can be seen as a tragicomic reflection on the chaos in the Middle East when thinking about how Asterix is supposed to look like Charles De Gaulle and considering that the triple entente (France, England and Russia at the end of 19th century) deliberately destabilised the whole area.

Anyway, for the invitation card of the Hamburg exhibition, I wanted Obelix to say: "These romans are crazy," in Arabic letters. This relates to a moment in the animation I presented in the show, Let Music Play? (2012), when the mosque architecture is described with occidental terminologies, and which somehow doesn´t work for the buildings at all. Then, I have a British commentator taking leave and delegating the task of commenting on the architecture presented in the work to a musician, which does not work either.

On a visual level, you have scenes in the animation where churches are compared to cinemas, or the Dome of the Rock is compared to a round living room. I love the idea of having thirty seconds of film in which you can look at the Dome of the Rock stripped of all political and religious contexts just as you would look at a living room. One curator from Tel Aviv commented negatively on this: he said he felt insulted although he found the idea intriguing. Nobody has commented on the exploding mosque, yet.

SBWhat influences have affected your approach to making work, and what has informed the ideas, concepts and notions that concern you?

MGThere are many artists who have been influential to me, but more so in the sense that I have found groups of relations amongst some artists in particular who experimented with similar ideas and forms under different conditions, times and systems: for example Klaus Merkel and Adnan Coker or Frederick Kiesler, Gregg Lynn and Rudolf Steiner. Inspiration also comes from coffee and reading.

At the same time, I love the sensual qualities of paint and physical bodies. I really like putting basins filled with water in front of a projection, for instance, because this adds a bodily dimension to the projection and engulfs the moving image into the exhibition space. If I think closely about it, it seems like my religious upbringing, although rather dry, had a big influence on the way I deal with space and material: I mean, the seductive moment.

SBOne work in the Hamburg show, was La Mediterraneé (The Mediterranean, 2010): a film collage that presents a brief history of the Mediterranean region as influenced by the book of the same name by historian Fernand Braudel, who insisted on looking at the Mediterranean as a space united by the sea: one in which a collective history is defined by the flux of trade, conflict and migration. Jens Asthoff writing for Frieze d/e noted how this work exemplified an approach you took to difference and repetition—an attempt at breaking down "borders of linear ways of seeing, thinking and knowing." Could you expand on this?

MGTo say something about La Mediterraneé specifically: I turned Fernand Braudel's wide-angle perspective, which drowns events such as coronations, wars and changes of government, within the longue durée, into a 15-minute filmette that is even more wide-angled, in which music, commentary, song and animation are fused.

On the one hand, the work thinks about the sheer pleasure in simplifications, general truths, principles, laws, and on the other hand, it expresses the need and joy in staying volatile, the love for anti-standardisation and anti-ossification. I haven´t figured out yet how these sides work together. But it is not only La Mediterraneé that is concerned with such ideas. In my work I often propose a generalised binary, like regionalism versus high-tech-architecture; then a third thing intrudes this order and reveals something about the construction of the binary.

SBLa Mediterraneé seems to have some kind of connection to your 2013 exhibition, Commercials, Mosques & Ceramics and Kunsthaus Baselland in 2013. How did this show expand on the Hamburger Kunstverein exhibition?

MGYou're absolutely right. I have always enjoyed making very disparate looking work, but until Commercials, Mosques & Ceramics I had never thought about showing disparate works in a continuum by tweaking them towards a similar surface or two dimensionality. The continuum seems to be the questioning of standards: in Reanimation of a body — Commercials for Jan Albers (2013), I show the production process of some of Albers' works in the customarily affirmative manner of a commercial.

In such films, art is usually shown together with the artist. But here, the materials are animated and build up to the work without the creator present at all. The focus is on the high-gloss character of the work itself, as would happen in a car commercial.

SBHow does this reflect your view of the systems of production within the art world and how they are presented?

MGIn general, I don´t understand why a colleague would be totally immersed in an assumption of a (unverified) system of art in an art fair, for example: from production, to transport, to booth, to collector.

To my mind, if you deal with certain kinds of problems over and over again (like what is a successful fair booth, for instance) you will design a certain set of practices to deal with these problems. In time, this set of practices becomes fixed, which often means that your understanding of what else is possible becomes limited.—[O]