Wang Gongxin: Video as the Perfect Expression

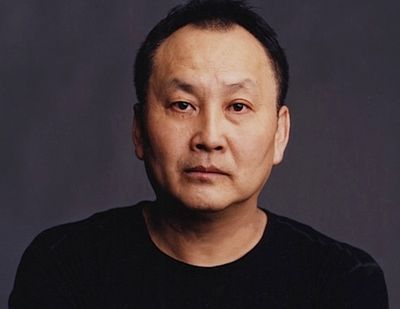

Born in Beijing in 1960, Wang Gongxin belongs to the post-1960 generation in China, who lived through the onset and dispersal of the 1966 Cultural Revolution.

Despite limited education available at the time, Wang started drawing at a young age, gathering just enough experience to be accepted into art school at the Capital Normal University in Beijing, where he was taught to paint in the matter-of-fact style of Soviet Socialist Realism.

Showing a natural preference for realistic depicton, Wang opted for Western painting over Chinese ink, all the while feeling the restrictions of painting in an institutional setting, where there was not much discussion about art itself.

Graduating into a teaching position in 1982, Wang was selected for a 1987 scholarship visit to the State University of New York, where he encountered the work of multimedia artists like Bill Viola, Nam June Paik, and Bruce Nauman for the first time at the Whitney Biennale, three days after his arrival.

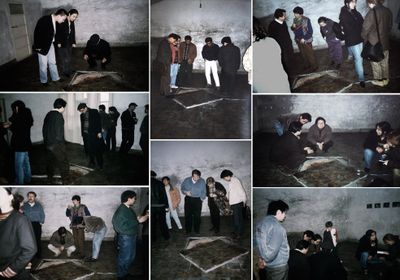

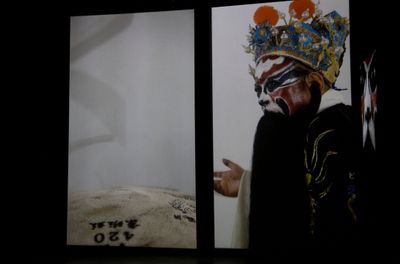

Contemporary video art offered Wang a new freedom, well-expressed in the artist's debut video installation The Sky of Brooklyn—Digging a Hole to Beijing, shown at Open Studio in Beijing in 1995, following Wang's return from New York.

To express his connection to both cities, Wang dug a well in the ground, where he placed a projector playing a video of the sky of Brooklyn. This initial experimentation with video followed with a group exhibition at the China Academy of Fine Art in Hangzhou, Image and Phenomena, in 1996.

Later video works are equally sculptural, creating immersive experiences, as with the nine-channel video installation, Relating-It's About Ya (2010), which replicates the cacophonic buoyancy of Beijing's streets, to the point of rendering one dizzy.

With a career spanning over four decades, Wang's universal visual lexicon has crossed the world from the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo.

In light of his first major exhibition in Australia, Wang Gongxin: Video Artist, at the National Gallery of Victoria (11 April–28 September 2014), Wang speaks to Ocula Magazine about his experience growing up in China, his thoughts about the younger generation, and the future of contemporary and video art.

LTYou trained as an oil painter in the Socialist-Realist style, which was the accepted doctrine after the Cultural Revolution in China. Can you tell us about your background and how you first became interested in art?

WGThe Cultural Revolution began in 1966 and ended in 1976. Two years after the revolution, the educational system resumed normal functioning status. In 1977, nation-wide college applications recommenced and all qualified applicants were accepted into higher educational institutions.

I was born in 1960, in Chinese we call our generation Liulinghou, or literally 'people born after 1960s'. This was a very special time in Chinese history. I first became interested in drawing in the middle of the revolution. At that time, we did not have access to a lot of education but we had a teacher in junior high school who encouraged us. I liked drawing and started practicing regularly around the age of 10 or 12.

Thanks to this early work, once higher education resumed, I was accepted into the art school of the Capital Normal University. Art education was still very much influenced by the Soviet Socialist-Realist style and I received very strict and serious training focused on the foundations of a subject's forms.

I chose Western painting instead of Chinese ink wash painting, or sculpture, because I was interested in the realistic style. While I was well trained and developed mature skills it was of course quite a restricted education, there was not a lot of thought or discussion about the nature of art itself.

LTTravelling to New York in the late 1980s was a significant moment in your career. You were immersed in groundbreaking video and multimedia art scenes, and confronted with new ideologies with respect to society, politics, and culture.

Can you discuss the experience of leaving China then?

WGIn 1982, I graduated with honours and became a teacher at the Capital Normal University. In 1987, I was lucky enough to be selected as a visiting scholar to participate in a cultural exchange program between our university and SUNY Cortland.

New York at the time was the center of the art world, full of museums and galleries where I became acquainted with different kinds of art. Coming from a very traditional and conservative background, the experience was full of surprise and excitement. It was at the Whitney Biennale that I saw contemporary video art for the first time and this opened up a brand-new world for me.

It was very fortuitous, almost like I was given a second chance, especially given I hadn't previously been able to 'choose' how I would practice art. Discovering video art opened a completely new world to me and allowed me to reconsider my career.

LTWas your shift to video art in some way a rejection of the authoritarian nature of Socialist-Realist painting in which you trained? Or, did you simply feel a deep connection to a previously unexplored medium?

WGTo some extent yes. But, I would rather say it was a re-discovery of myself and the chance to make a second choice with respect to the direction of my artistic career. If given the opportunity to explore or investigate new forms of art, you should do so based on your own interests, and find your own way.

As a video artist, I gradually found my own voice and now know that the medium is the perfect form of expression for me. If you look at my career, you will understand what I just said. My artistic practice began with The Sky of Brooklyn in 1995, when I returned to China after living many years in New York City.

Three days after I arrived in New York, I saw video art at the Whitney Biennale. I witnessed the rise of the medium, and very much admired the work of pioneers like Bill Viola, Nam June Paik, and Bruce Nauman.

While I was fascinated by video art, I did not immediately transfer my practice to the medium. At first, video was just another artistic reference. Before working as a video artist, I also worked in many other mediums including sculpture and installations, some of these features transfer to my early works from the 1990s.

In 1995, my wife Lin Tianmiao and I returned to Beijing, and an idea struck me. To express my thoughts about the connection between my two lives in China and America, I dug a well and put a monitor into it, playing a video of the sky of Brooklyn. The result was The Sky of Brooklyn—Digging a Hole to Beijing (1995).

After this work, I noticed I was very interested in video. The artistic possibilities encouraged me to try more. I took part in a group show in Hangzhou in 1996, after which my career as video artist began.

LTAs a Chinese artist living in New York and Beijing you have bridged two distinct cultures. How much of your work is autobiographical and how you see yourself in the context of Chinese art today?

WGThe first time I travelled to United States, I thought China and U.S. to be two completely different worlds—they felt so far apart you could not imagine they existed at the same time and I couldn't see myself returning to China within 10 or 20 years. But now, in this era of highly developed technology, globalisation, and multimedia connectivity, it is a global village—a completely integrated world, at least geographically speaking.

You never feel disconnected. Living between two cities can give you an interesting perspective: one afternoon you are taking a nap in your Beijing studio, then the next day, you are having lunch in New York, a completely different environment, way of living, language, behaviour, and so forth.

This contrast enables me to observe things very closely and makes me more sensitive to what is around. For example, if you stay in a room full of red walls, at first you feel a little bit strange or uncomfortable, then you get used to it, then you feel nothing strange. Later, when you come out of the room (and enter into another room with a different colour), your sensitivity will return and become alive again.

I feel that existing in this state of sensitive thought and observation gives me an opportunity to reflect on where I am living and what kind of life I am leading. But I no longer see the two cities as opposites, instead I see them an 'integrated world', like day and night, they can be transformed into each other and that is interesting for me.

LTI understand you teach art students in China. What are your observations about the next generation of contemporary artists and what are your hopes for the future of contemporary Chinese art?

WGI don't teach any more. From 2002 to 2007, I taught video art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, which had a new program called New Media Arts Major. During my time there, I enjoyed connecting with the freshness and energy of the students. They are very quick to acquire new skills, especially new technology—I even had to learn from them sometimes given that video art is so closely aligned with changes in technology!

Young artists today are different from artists from our generation: we look at art with seemingly, more responsibility within society, in a more idealistic way; they look at art from a more personal or realistic angle, based on their own interests or habits.

It seems that they are equipped with easy access to a high-tech environment—computers, video games, mobile phones, digital cameras are second nature to them so they have a good technical foundation from which to work as video artists. The problem for video artists in China today is that in a money-orientated society like China, the market for video art is very small.

Consequently, there is only a very small group of video artists working in China and that brings many challenges. Two to three young artists I've mentored in the past have already emerged. I hope there will be more young artists working with video in the future and wish them success not only with respect to international recognition but also with respect to making great art.

LTTurning to your exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, this is one of your first major exhibitions in Australia—how did it come about?

WGYes, this is my first major show in an Australian national gallery. I am very grateful to the National Gallery of Victoria for the opportunity and the consideration with which they have presented the exhibition. I had been to Sydney and Brisbane many times, but never to Melbourne and had only ever seen pictures of the NGV.

At first, we corresponded by email. They inquired about the availability of Dinner Table (2006) and asked if they could have a show with me. The work was acquired, the shipping arranged, I got paid. We are living in a virtual world. In the past, we met in person. All of these things were done via email over a year and a half or so. My assistant Leon was very involved, so when I flew to Melbourne, they joked that they knew Leon better than me.

LTThe exhibition is called Wang Gongxin: Video Artist, an unambiguous description of yourself as an artist. However, there are many painterly and indeed sculptural elements to your work—colour, light, composition, texture.

Can you discuss the role of painting and sculpture in your work?

WGI like this simple and interesting title for the show—it does not refer to any literary meaning, theme or subject. But for me, and for all the Chinese artists, I think it is a very clear title.

Twenty years ago contemporary art was in its infancy in China and relatively unknown. Now many Chinese artists are having exhibitions around the world. Initially, these international exhibitions were always labeled as 'Chinese' or 'Video Artist from China'. The implication was that the work was as interesting because the artists were from China, if you know what I mean.

Now that the scene is more mature, 'being from China' is not so important. Of course I do not deny the fact that I am a Chinese artist, who comes from, was educated in, and essentially lives in China—this is who I am. However, it is important to me that the title of this exhibition refers to my work as a video artist rather than categorising me as an artist from China.

An artist is always connected to what he or she has experienced or is experiencing—their cultural identity. I was educated in the Soviet Realist style of painting, which focused on strict and serious training in forms, patterns, colors, and contrasts. This experience, including the good and bad, is a part of who I am and in some way related to my work.

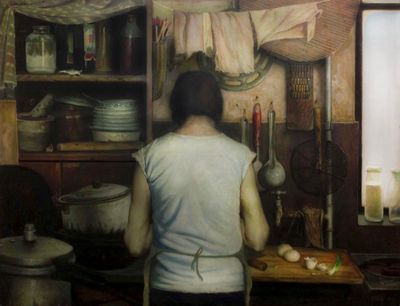

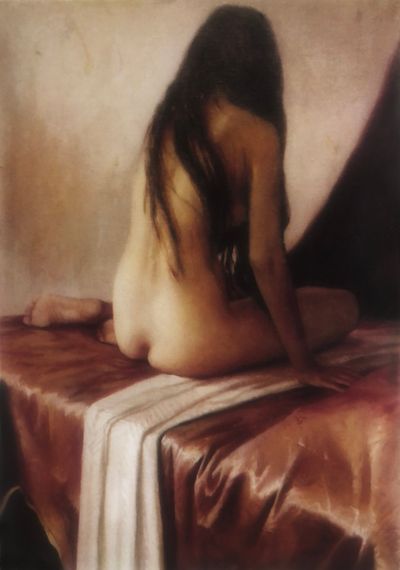

The exhibition includes three major installations, Relating-It's About Ya (2010), in which viewers are confronted with the chaos of Beijing in a vibrant display of sound, colour, and movement. Basic colour (2010), which depicts extreme close-ups of a naked body gradually hidden and abstracted by powdered pigments.

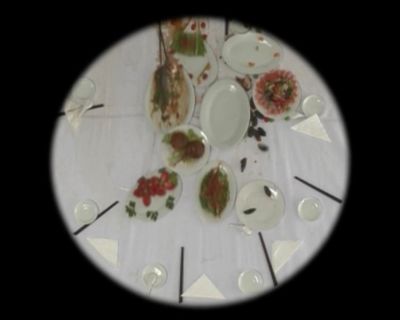

The third work, Dinner table (2006), depicts a Chinese banquet laden with carefully presented dishes—projected onto a steeply tilted white table—defying gravity to slowly slide upwards.

LTHow were the works selected and what are your hopes for the exhibition?

WGDinner Table was acquired by the NGV and the exhibition was an opportunity to introduce it to the public. After considering the floorplans we decided to show it with my recent major works. I would have liked to show more but space limitations meant this was not possible.

Relating-It's About Ya is a large and powerful piece that reflects my major artist concerns. To balance the louder sounds and powerful presentation of Relating-It's About Ya, we chose a very quiet and delicate work Basic Color. I think they work well together. Being an artist, I always want wider audiences to experience my work, to interact with them, reflect on them, and communicate with them.

I am very pleased that this exhibition has such a long running time, nearly six months, which will enable many visitors from around the world to come and see the show. The NGV has done an excellent job with all aspects of the exhibition. Melbourne is an international city, with many colleges and universities and many students from China study there.

All these things make me very happy. I believe many of them will see the show and leave valuable comments. It would be wonderful if the exhibition could travel to other cities, or even other countries, enabling more people to see my art and for me to gain valuable feedback from fellow artists and scholars.

LTYour works focus on your observations of society and the things around you, critiquing contemporary urban life and shifting our understanding of the every day. If you had to describe the key message you are trying to communicate, what would it be?

WGAs an artist, I prefer to communicate ideas with my audience via my work. Everything I want to say is within my works. If the written language can convey my message, then I would not need to produce my work.

I want people to see the works, to feel them in person, experience them, understand them, and interact with them, especially with Relating-it's about Ya.

LTWhat's next for Wang Gongxin—what are you working on now?

WGI am currently participating in an international group show called LAND SEA SKY, on view in Shanghai. It is curated by an old friend, Kim Machan, who comes from Brisbane, maybe you know her?

A new work of mine is included in the exhibition. Next year I hope to have a solo show in Beijing or Shanghai, maybe both. I am also currently working on a project with a French company. —[O] ****