A Century of Black Figuration Across Black, African, and Intra-African Art Histories

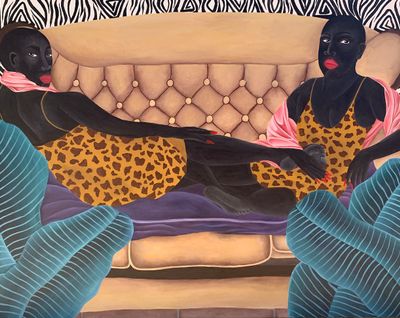

Zandile Tshabalala, Two reclining women (2020). Acrylic on canvas. 122 x 91.5 cm. © Zandile Tshabalala Studio. Courtesy the Maduna Collection.

When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration in Painting at Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town (20 November 2022–3 September 2023) sutures a globally diversified legion of Black, African, and African diaspora artists through an age-old measure: time.

The exhibition's curators, Koyo Kouoh and Tandazani Dhlakama have gathered works by 154 artists, loaned from over 70 locations, to create a historical continuum of geographically diffused artistic movements and painterly traditions that articulate the many iterations of Black life.

The exhibition highlights crucial historical movements from the 1920s to the present, and combines creative gestures from across Brazil, Cuba, Kenya, Mozambique, Senegal, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and beyond. The result is a fluid and refreshing collection of works that explore the interconnections between art histories, movements, and techniques normally defined by place and time.

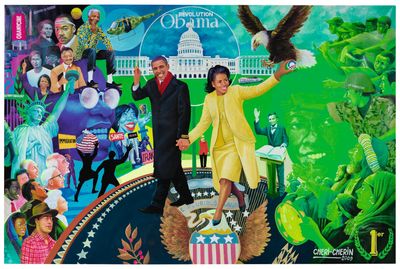

Nigerian modernism, which began in the 1900s, is represented in Ben Enwonwu's works, while paintings by Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence, among others, hark back to the Harlem Renaissance that emerged in the 1920s United States. The Zaire School of Popular Painting, born in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1970s, is represented by artists such as Chéri Samba, Chéri Chérin, and Matundu Tanda.

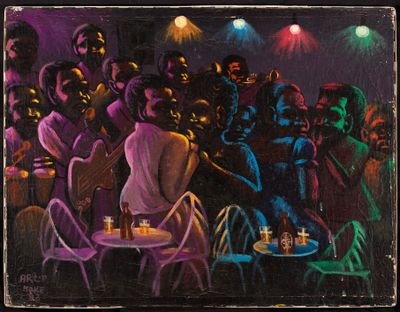

The show is organised into six sections across the museum's third floor: 'The Everyday'; 'Sensuality'; 'Joy and Revelry'; 'Spirituality'; 'Repose'; and 'Triumph and Emancipation'. Together, they reflect on how African and African diaspora painters envision, present, and examine their communities and issues of concerns, from labour and health to economic and social mobility.

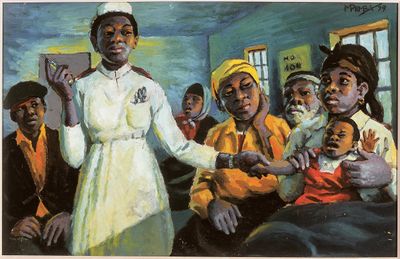

Opening the first section, 'The Everyday', are paintings of various sizes hung mosaic-style along tangerine and fern-green walls. South African painter George Pemba's small, rectangular oil on board At the Clinic (1979) epitomises the curatorial intent to highlight the quotidian grace of Black communities who patiently create joy, beauty, and homes—and often in 'under-developed' conditions.

At the Clinic stages a quintessential scene in a township medical facility. Brushstrokes embody several patients seeking a nurse's attention as she prepares to administer a needle to a young child crying in his mother's arms, fearful of the sight of suffering brought forth by the medicinal tool.

In Pemba's work, colours offer glimmers of light amid a scene revealing the daily undersupply of essential social services for Black and African people. Maroon brown paint casts the Black skin of hopeful patients, with blotches and blends of pale blues and ashen greys pressed into their faces and limbs. Swathes of amber and red accentuate the patients' dress, while the nurse—the scene's focal point—is painted wearing traditional white.

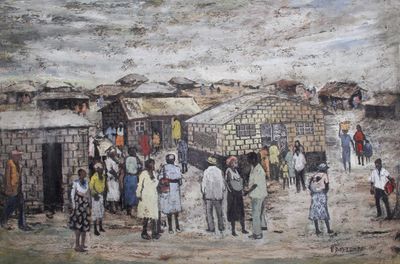

In the same section, reinforcing the curatorial intent to promote investment in Black and African communities, the prominent Zambian painter Petson Lombe's medium-sized oil on board painting, Township Scene (1981), serves the artist's interest in recording the happenings he has observed across various cityscapes and rural planes.

Calls for solidarity, preservation, and the celebration of community in such paintings resonate with the exhibition's title When We See Us, which draws from a 2019 American drama mini-series, When They See Us, directed by Ava DuVernay.

Unlike DuVernay's critique of violence against Black bodies, the exhibition introduces the museum as a refuge from ecosystems founded upon racialised attack. Particularly in South Africa, where skin is used to manufacture inequality—a point that somehow finds its countermeasure in the exhibition's focus on race-based figuration.

Close to 15 percent of exhibiting artists were born after the 1990s, which, in the context of a survey of Black figuration, both criticises and reproduces the art world's interest in flooding contemporary art markets with figurative paintings by young Black artists—ones that often conform to representing figures of African or African descent with coal-coloured skin, posing self-assured in imported wears.

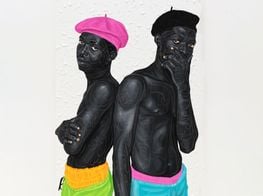

This aesthetic tendency is evidenced across When We See Us. Ghanaian painter Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe's life-sized oil on canvas, View of Yoei William (2020), honours a jet-black dandy in a tailored turquoise suit and gold rings, clutching a fuchsia petal. While Cameroonian neo-pop painter Anjel (Boris Anje)'s acrylic-and-silkscreen print on canvas, Ying and Yang (2020), depicts a young man with jet-black skin posing in a black tracksuit, offering a taunting peace sign.

Anjel's subject stands in front of a mass of logos emblematic of luxury brands on a blood-red background. Logos are dotted on various parts of his body, reminiscent of the multitude of fashion and market wares, both genuine and counterfeit, peddled to youth in and out of Africa.

Works like this sustain a painterly tradition that intersects with contemporary cultural phenomena like Instagram, whereby portraiture operates as a mode of self-actualisation and notoriety. In doing so, they also replicate material culture and justify society's relationship with consumer brands, saying less about an artist's painterly verve, than society's persistent fascination with global corporations like Gucci—the exhibition's sponsor.

That being said, as such landmark museum shows do not ordinarily exist in Africa, the choice to democratise visibility for younger painters within and beyond the continent is vital. Even more critical is to honour under-documented artistic figures whose dexterous works are exhibited here, such as Moké and Gerard Sekoto, and the practices of women artists, both African and of African descent.

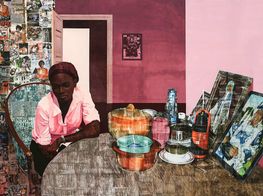

Several exceptional works stand out due to their progressive approaches to figurative painting with mixed media. Bellyphat (2016) by Tschabalala Self, exhibited in isolation at the entrance of 'Sensuality', is a large-scale painting of a woman whose body is rendered in a patchwork of fabric, oil, acrylic, and flashe. Her belly protrudes as she smiles, while the brown-bodied man behind appears to signal the reproductive force of the Black family unit.

...as such landmark museum shows do not ordinarily exist in Africa, the choice to democratise visibility to younger painters within and beyond the continent is vital.

Mickalene Thomas' Never Change Lovers in the Middle of the Night (2006) blends rhinestones, acrylic, and enamel on a rigid, wooden panel and renders two scantily clad, wide-thighed Black women with afros and limbs interlocked, one thrusting atop the other, as if engaged in a sexual act. The artist's blend of materials creates a vigorous placard encouraging Black women to reclaim agency over their contested bodies.

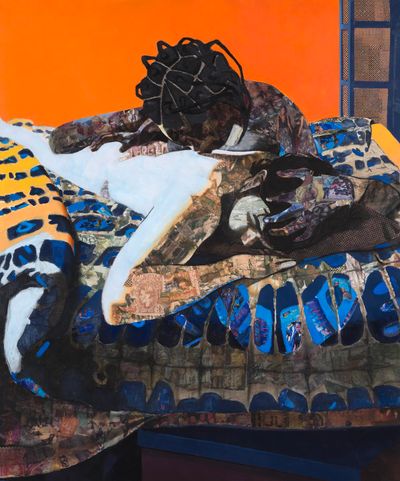

Exhibiting an equally controversial scene is Njideka Akunyili Crosby's Re-branding My Love (2011), which deploys her signature photo-transfer-based painting method to create a large collage with charcoal and acrylic that combines the emotional, political, and cultural terrain of two worlds: the U.S. and the artist's native Nigeria.

In this work, the artist unloads the weight of both domains through a scene where aged images of Black women are layered to form and reckon with the body of a Black woman lying with her head hung low, sinking into a naked, sleeping white man.

Crosby's painting speaks to how the exhibition's grand assemblage of works opens channels of intersectional relation among African and diasporic artistic communities, who, in responding to the internal conflict wrought by the fatal politics of skin colour, mine their existence with and as the other.

While no curatorial art can revoke the damage done by racialised hierarchies of violence, this convening of critical works—from 74 institutional and private collections around the world—builds a compelling case that artworks and artefacts of Black and African descent, which often reside far from their cities and cultures of production, should find their way to African soil.

By staging a global survey of Black figurative painting on the continent, the exhibition, a curatorial triumph, demonstrates that restitution, comfort, joy, security, and self-actualisation are possible when transatlantic Black, African, and intra-African communities build on networks and artistic genealogies that have been forged with and for each other.

If the exhibition travels within and beyond the continent, it would be elevated with the addition of seminal painters like Noah Davis, Kerry James Marshall, Yusuf Grillo, Aina Onabolu, and Obiora Udechukwu, who would drive a more labyrinthine discourse into figuration. —[O]