Claude Cahun: An Intimate Dialogue Between the Self and Other

Barbara Hammer, Lover Other (2006) (still). Video, colour and B&W, sound. 55 min. Courtesy the Estate of Barbara Hammer; Company Gallery, New York; and Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York.

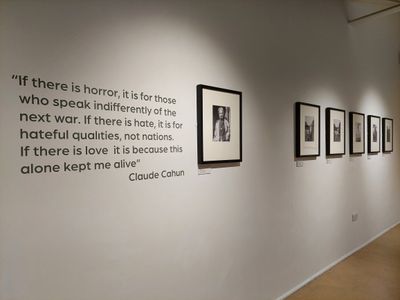

First presented in 2015 at London's Southbank Centre as part of the Women of the World Festival touring exhibition organised by Hayward Gallery, Beneath This Mask brings together 42 contemporary giclée prints of French photographer Claude Cahun's performances of gender and self, attesting to the fluidity of both.

The images on view are made from scans of Cahun's original photographic self-portraits, which were never shown during her lifetime, just as most of her negatives have been lost. In many ways, the exhibition is a testament to one of the 20th century's most enigmatic artists, whose legacy endures, and continues to evolve with the times.

Having recently shown at Qube, Oswestry (30 April–5 June 2022), and set to open at Gracefield Arts Centre, Dumfries (27 August–1 October 2022), the U.K.-centric exhibition will then travel to Turner House Gallery, Penarth, in 2023 (11 March–9 April).

Born into a family of French intellectuals, Claude Cahun grew up as Lucie Schwob. She had a famous uncle, Marcel Schwob, who was a prominent Symbolist writer. His book Vies imaginaires (Imaginary lives) (1924) mixes life-writing with fiction, telling 22 semi-autobiographical tales about 22 historical figures from Pocahontas to Lucretius.

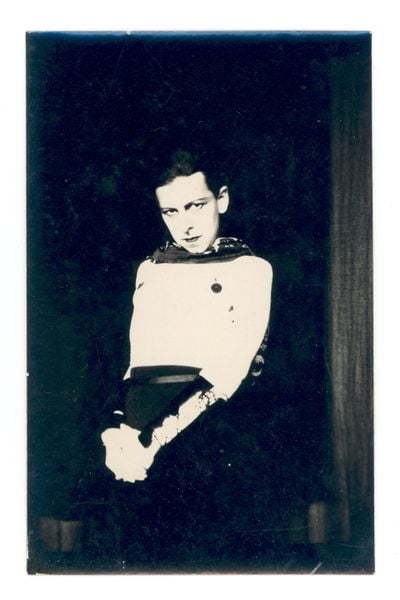

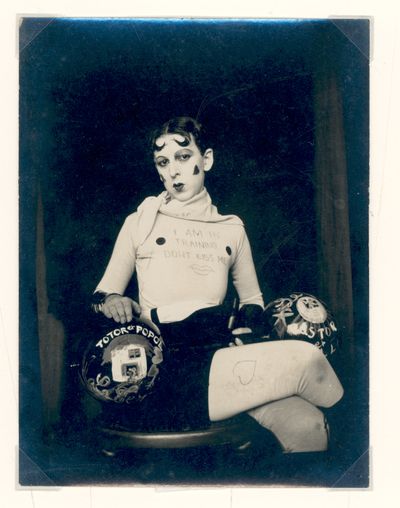

It's fitting then, that Schwob's niece would have a similar fascination with the theatre of identity; Cahun presents gender as an elaborate performance, demonstrating that personhood can shift and be fluid.

Before adopting the gender-neutral pseudonym Claude Cahun around 1914, Lucie Schwob tried on different names: Claude Courlis, a homage to the long-beaked bird species, and Daniel Douglas, a reference to Lord Alfred Douglas, who translated Oscar Wilde's 1986 play Salomé from French into English, and was later Wilde's lover.

While first and foremost a writer, Cahun's name is also associated with the series of self-portraits shot in collaboration with her lover Suzanne Malherbe, known by her masculine persona, Marcel Moore.

Schwob and Malherbe met as schoolgirls in Nantes in the late 1910s and soon began their relationship as lifelong partners and collaborators. When Schwob's divorced father married Malherbe's widowed mother in 1917, Lucie and Suzanne became sisters as well.

The relationship between the pair forms the subject of Barbara Hammer's film Lover Other (2006), in which Hammer recounts the couple's resistance to the Nazi occupation of the isle of Jersey in the English Channel, where they lived from 1937 until the end of their lives.

The pair were famous amongst Jersey's residents, even before they started sending 'paper bullets' during the Nazi occupation of the island.

These paper bullets comprised small cartoons and messages left in cigarette packets, on the walls of German army sleeping quarters, among other places, in the hope of inciting dissent amongst soldiers. One woman tells Hammer about how the duo were thought of as 'rather strange ladies' but were generally accepted on the isle as artists.

Throughout her life, Cahun referred to Moore as her 'other' as well as her lover.

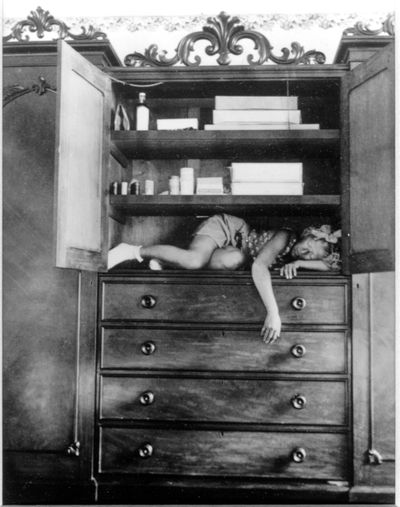

On the island of Jersey, Cahun and Moore shot elaborately staged portraits on the beach, and in and around their home. Within Beneath This Mask, these small black-and-white images attest to Cahun's anticipation of photography as a device for unpicking gender's fixity, foreshadowing current debates.

Indeed, in 2017, the National Portrait Gallery, London, paired Cahun's work with contemporary artist Gillian Wearing's because of their mutual interest in disguise, costume, and masquerade. Notably expressed in Keepsake (1932), where Cahun's shaved head rests within a bell jar, dislocated from the rest of her body.

The glass around the artist's gaze, which meets the viewer's eyes, limits the risk of contagion, while her head is under close inspection as if her entire body was being dissected and then transfigured into a memento—a keepsake, of a past self.

On the first page of Cahun's Disavowals, the book she wrote in Paris before leaving for Jersey, the artist writes: 'Until I see everything clearly, I want to hunt myself down, struggle with myself.'

Five-hundred copies of Disavowals were published in 1930 under its original title Aveux non avenus (Disavowed confessions). Cahun was still living in the French capital then, where she hosted salons attended by Surrealists like Salvador Dalí and André Breton. Breton hailed Cahun as 'one of the most curious spirits of our time' but was openly homophobic, allegedly avoiding Cahun and Moore when he saw them in Parisian cafés.

Disavowals was commissioned as an autobiography, but rather than writing a straightforward memoir, Cahun critiqued the genre's pretensions to self-knowledge. She used the space to negotiate questions of selfhood and smuggle in her perspectives on widespread cultural conservatism in France then.

Cahun presents gender as an elaborate performance, demonstrating that personhood can be fluid.

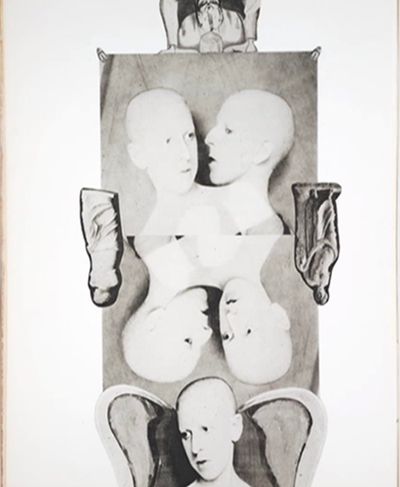

The book also contains a set of photomontages made in collaboration with Moore that would be further developed once the pair settled in Jersey, away from Paris' artistic sect.

Gillian Fox, who curated Beneath This Mask, was initially drawn to Cahun's images because of their childhood mischief: their ability to maintain an inherent sense of play and a lightness, while handling issues of identity politics.

There's an image of young Cahun in bed, hair spread out across the pillow, with a white box signalling the area that would later be cropped. By eliminating the bedroom context, the artist's face, specifically her eyes, become the focus.

The oldest image in the exhibition, Self-Portrait (1945), shows Cahun on the other side of her life, with a Nazi badge between her teeth. She stands under the archway of her home in Jersey, having just been released from incarceration, narrowly escaping execution.

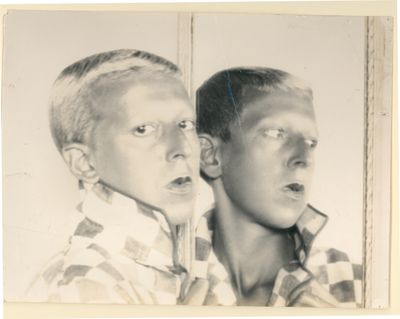

Another iconic image shows Cahun in front of a mirror wearing a checkered jacket, taken before moving to Jersey. As the artist looks into the camera lens, her reflection gazes beyond the frame at the unseen. Not featured in Behind This Mask is an identical image of Moore standing before the same mirror, dressed in a matching blue and white striped jumper and hat. Through the mirror, she smiles at the camera.

Throughout her life, Cahun referred to Moore as her 'other' as well as her lover. Historians such as Tirza True Latimer have highlighted the importance of Moore's involvement in the making of these portraits, often solely attributed to Cahun.

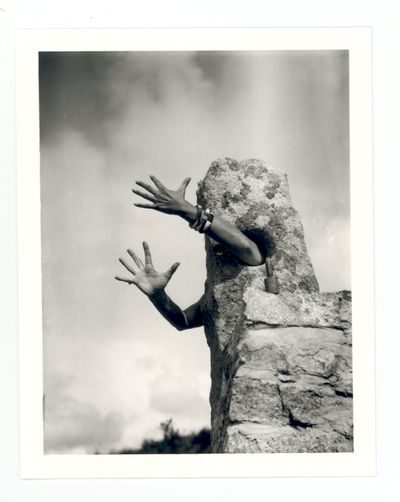

The doubling of Cahun's physical form is notable in images produced throughout the 1930s. In one photograph, a hand emerges from a shadow to meet another hand that is painted gold. Neither hand looks particularly real: they seem too singular to belong to the same person. Just as Cahun's head is encased by the bell jar in Keepsake, the hands float across the dark contours of the photograph, separated from their bodies.

Elsewhere, Cahun is doubly exposed with an image of her body superimposed over another image of herself floating in the English Channel. The body is flipped in the double exposure and Cahun's hand reaches behind to grasp her double's foot; the curve of her body forms a caress around her image. The 'hunt' for self-perception is depicted as piecemeal and ghostlike; unfulfilled.

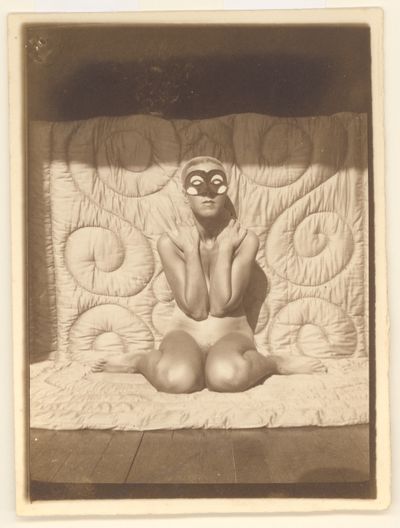

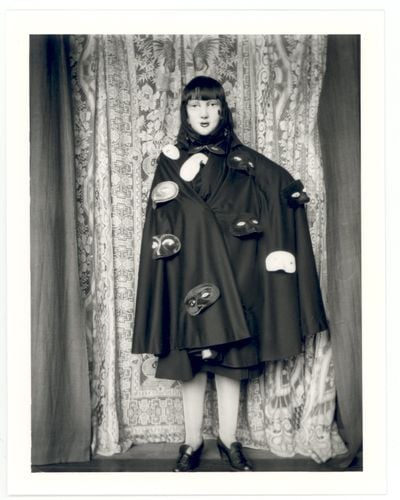

Hammer was also interested in Cahun's use of masks. Cahun believed that the masks she made were 'so perfect that when they happen to encounter one other on some great open space of [her] consciousness, they don't recognise each other'.

In Untitled (c. 1928), Cahun wears a cape covered with black-and-white masks with static, painted eyes. In another image, she places her hands on both sides of her face, stretching her cheekbones as if to put on, or peel off, the mask that is her face.

In her writings as with her images, Cahun sought to demonstrate the infinite plurality of the self: 'I will never finish removing these faces,' she wrote. The 'hunt' and the 'struggle' for clarity around the self that manifest in Cahun's desire for multiplicity are distinctive traits in her image-making.

None of the images displayed in Beneath This Mask were shown to the public during Cahun's lifetime. As historian Carolyn J. Dean notes, the photographs were 'personal researches, not statements of social intent'.

Looking at them now, it becomes clear that the images associated with Cahun were part of an intimate dialogue between Cahun and Moore, Schwob and Malherbe: testing the boundaries between internal and external worlds, between the self and the other. —[O]