Mit Jai Inn: The Artwork as Gift

Working from his outdoor studio in Chiang Mai, Mit Jai Inn's tactile and transcendent paintings are made through his being in the world, for the world.

Mit Jai Inn in his studio. Courtesy Art Basel. Photo: Kanrapee Chok for Art Basel.

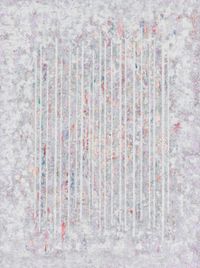

Yet despite an active exhibition record across Southeast Asia, it is only in recent years that the artist's kaleidoscopic paintings, made up of accumulated layers of old oil paint, gypsum powder, pigments, acrylic paints, and linseed oil have found an international following.

'Pre-2010, Mit grappled with the art world and whether he wanted to be part of it, because for him, art is intrinsic to life,' explains Melanie Pocock, curator at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, which is hosting Mit's first institutional solo exhibition Dreamworld (15 September–21 November 2021), accompanied by a monograph published with ArtAsiaPacific Foundation.

First studying at Silpakorn University from 1983 to 1986, Mit left to study at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna between 1988 and 1992. It was there that he encountered Franz West, who came upon the artist's work while doing the rounds of students' studios and invited Mit to assist him.

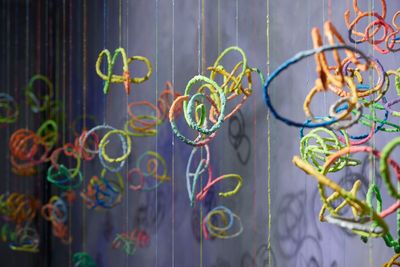

With a shared affection for tactile, polychrome surfaces and scale, Mit and West's practices are also driven by concerns for social engagement. Deeply influenced by the Fluxus movement, and in particular Joseph Beuy's concept of social sculpture—that every aspect of life can be considered creative—the notion of free distribution, along with the joy of colour and the concept of the artwork as a gift, has continued to guide Mit's practice.

For his graduation exhibition, Mit made 1,000 tactile fluorescent objects—ranging from shelves, lamps, and furniture—which lined the university's corridors. Inviting people to take them home, the exhibition continued with a map, allowing objects to be visited in-situ.

After returning to Thailand, he helped organise Chiang Mai Social Installation (CMSI), recognised as the country's first public arts programme. Initiated by Uthit Atimana, a lecturer at Chiang Mai University's Fine Arts Faculty, alongside other artists, scholars, and social activists, CMSI sought to disrupt the conservatism of Thailand's art scene.

Between 1992 and 1998, events included a large festival that placed art in temples, graveyards, streets, civic squares, and other public places—a method of dispersal that continues to hold influence, as seen in Dr Apinan Poshyananda's city-wide curation of the recent Bangkok Art Biennale.

CMSI's second festival in 1993 brought international artists including David Hammons and Lawrence Weiner to Chiang Mai thanks to Mit's connections, yet the artist's own work was presented anonymously. 'I never saw the objects that I made for CMSI as "my" works', he has explained.

As Melanie Pocock notes, the art object is a by-product in Mit's process. 'It's not about the beauty of the object,' she proclaims. 'He wants it to be a feeling that spreads.' Mit achieves this in a number of ways, one of which is scale.

Gargantuan scroll paintings, such as Planes (Electric) (2019) presented at Art Basel's Encounters section in Hong Kong in 2019, invite a corporeal engagement with the viewer, 'like a hug'.

His more intimate paintings emanate gently outwards, as with the 20 small unstretched canvases forming 'OOBE' (2019)—standing for 'out of body experience'—their light hues interrupted by a curvilinear opening in each work. Arranged side-by-side, the works lined three outer walls of a Buddhist hall on Jim Thompson Farm in Nakhon Ratchasima.

Mit also willingly imparts his method, which involves spreading paint using his hands, fingers, and occasionally a palette knife, to assistants and volunteers, as with his hanging scroll Planes (Hover, Erupt, Erode) (2018) at the 21st Biennale of Sydney.

The invitation to engage in the art-making process does not stop at installation. Using unstretched canvas, works like Untitled (Patchworks) (2000), re-presented at Yavuz Gallery in Singapore in 2015 (Patchworlds, 30 May–19 July 2015), comprised over 100 small painting sections available to be lifted, rifled through, and repositioned at will.

In their myriad ways of being exhibited and experienced, Mit's paintings encourage viewers and curators to consider new possibilities whilst providing a means of making sense of the times.

Thus, while some of his titling may explicitly reference political events—as with Royal Marketplace, the title of a recent solo exhibition at Rossi & Rossi in Hong Kong (5 December 2020–20 February 2021), which was drawn from a Facebook group set up as a free space to discuss the Thai monarchy—the work itself is not so.

His series 'Junta Monochromes' (2016), for instance, included in an online exhibition with Silverlens (3–23 December 2020), made use of colour to move through 'accumulated political drama' at a time when 'it was hard to sense a future.'

With recent support from galleries and institutions worldwide, Mit's practice has reached a new stage where colour can emanate yet further, reaching towards the artist's vision for art as a 'utopian dream within everyday life'. —[O]