A good neighbour? The 15th Istanbul Biennial

Fred Wilson, Afro Kismet (2017). Installation view: 15th Istanbul Biennial, Pera Museum, Istanbul (16 September–12 November 2017). Courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery. Photo: Sahir Uğur Eren.

The 15th Istanbul Biennial, titled a good neighbour and curated by Scandinavian artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset, offers a welcome reprieve to a trend in curating that favours ever-larger exhibitions with more artists and more venues. With six locations all within walking distance from each other and 56 artists showing 150 works (30 of them are new commissions), a good neighbour operates as a modest antidote to the curatorial hubris of scale (Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev's last edition with its 36 venues being a case in point, and the didactic activist fervour of documenta 14).

If anything, this biennial genuinely wants to start a conversation that is not so much directed as it is artist led. Instead of a curatorial statement, Elmgreen & Dragset posed 40 open questions about who, or what, a good neighbour might be—neither a banal nor naïve inquiry when looking at the global state of affairs that has left Turkey grappling with the aftermath of the 2013 Gezi Park protests and the failed coup attempt of 15 July 2016. Turkish authorities continue their crackdown on civil liberties, freedom of speech and of the press, and mass arrests of public servants and political opponents of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's AKP party. Terrorist attacks in Istanbul have further destabilised and polarised the country and Turkey's closest eastern neighbour, Syria, remains entangled in a brutal civil war with millions displaced. To the west, Turkey's neighbours cannot seem to stem the tide of populist and xenophobic politics. In such a rough neighbourhood, what is the role of art and artists when it comes to thinking about ways through which conflicts—both real and imagined—might be mediated on a personal, and yet still political, level?

This biennial finds resilience in the understated. This is best illustrated by the exhibition in the Galata Greek Primary School, which, together with the Pera Museum, is the most effective of the biennial's venues. At the Greek Primary School, Dan Stockholm's House (2013–2016) consists of scaffolding on which he has mounted negative plaster casts of his hands, made after he touched the entire outside surface of his father's house after his sudden death. It is a tactile memorial to loss and mourning, with the scaffolding appearing fragile, almost transient, like life and memory. Loss is also the subject of Erkan Özgen's short video Wonderland (2016), which shows Mohammed, a 13-year-old deaf and mute Syrian refugee, recounting his flight from Kobani to Turkey. Seated on a carpet, the boy gesticulates the violence of war and escaping his home for the safety of another temporary one. It is a hauntingly visceral expression of a pain that is inexpressible.

Memories of home continue in Andrea Joyce Heimer's narrative paintings, which detail her childhood in Montana (USA) in the form of mesmerising tableaus ridden with teenage angst, insecurity and repressed sexuality. Racial tension and class divisions, but also the quirkiness of neighbours and living with other people, form the subtext to her work. Her protagonists—family, neighbours, friends, schoolmates and foes—resemble figures on ancient Greek vases; the scenes, a contemporary version of medieval illuminated manuscripts. One painting shows diners raising their glasses to a naked woman who stands proudly on the dining table displaying her pubic mound, while a younger woman inquisitively pulls down her pants in a bathroom painted above and to the right of this scene. The pubic mound is the point of visual attraction in the composition—in the work's corner there's a painter's easel with a canvas depicting one. Titles are written neatly with pencil on the wall, with mistakes scratched out, adding an explanatory but also an additional imaginary layer. In this case it is: My Sister's Bush Was Glorious And Full And The Color Of Campfire Flames While Mine, Still Struggling Through Puberty, Was Patchy And Mousy And In Her Presence I Felt Like An Unfinished Drawing (2016).

The installation and placement of most works at the Galata Greek Primary School is sensitively done with the architecture of the school still shining through. Even if not site-specific, it is as if each and every work has somehow attained that quality by probing how space itself becomes a divider or a container of privilege, a place of belonging, or conversely, one of estrangement. The latter is best exemplified by Lungiswa Gqunta's installation Lawn 1 (2016/2017), made from a mass of upturned broken Coca Cola bottles filled with dyed petrol, a strategy used in the artist's native South Africa to fence off property. During the Apartheid era, lawns were indicators of affluence and white racial privilege. While the Coca Cola bottles underline wealth disparity and the broken dreams of mass consumption in the wake of global hyper-capitalism, Gqunta's patch of green holds the promise of rebellion: petrol-filled bottle, or Molotov cocktails, are the poor man's grenade.

Both Olaf Metzel and Leander Schönweger's installations, Sammelstelle (1992/2017) and Our Family Lost (2017) respectively, ponder the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion. Entry to Metzel's piece is via a turnstile, restricting the flow of passage. It is the type of revolving door that is typical for prisons, checkpoints and borders. Inside corrugated iron lines the walls, occasionally peeling off, damaged and scratched. Whatever shelter this room provides, it is coming apart. In Our Family Lost, Schönweger presents rooms and doorways that become progressively smaller and smaller until access is impossible. What first seemed welcoming is now confining.

At the Pera Museum, the contrast between the idealisation of nature vis-à-vis the brutalism and devouring dominance of the built environment is striking. Alejandro Almanza Pereda's Horror Vacui (2017) consists of idyllic Romantic-style landscape paintings that the artist covered partly with a concrete slab. This material intervention comes especially to life among the permanent collection of the Pera Museum on the second floor (though the paintings also feature on the museum's 5th floor, among other biennial works). The meticulous and ornate framing of the paintings portray a contained—and to an extent pruned—nature, which comes undone by the ruthlessness of the cement, which is splattered messily on the painting, wall, and floor.

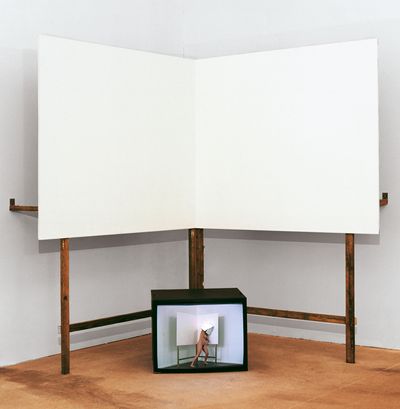

The tension between containment and liberation is distilled into a focus on gender politics on the museum's fourth floor. A group of works includes an older performative video, Hausfrau Swinging (1997), by Monica Bonvicini in which a naked woman violently bangs her head against the walls, her head depicted as a house. Like many feminist artists before and after, Bonvicini condemns the domain of the Hausfrau (housewife) as a space of domestic confinement: a prison with strict roles. She references Louise Bourgeois' 1946–7 photogravure Femme Maison, exhibited in the same space, which shows a naked female figure, less violent and more ambiguous, also depicted with a house instead of a head.

While concentrating on feminist interpretations of home, family, and reproduction on one floor certainly drives home a point, it also compartmentalises, and to a degree cramps this theme. Nevertheless, one highlight is Gözde İlkin's gorgeously embroidered fabrics based on family photographs, through which sheets, curtains, handkerchiefs and tablecloths with floral motifs, sourced from her family, provide the backdrop for some mischievous gender bending. One fabric shows the silhouettes of four women posing for a photograph; their clothing, posture and hair-dos are distinctly feminine but the artist has given them all moustaches. Another one shows three men, heavily moustached, bespectacled and with receding hairlines, handling delicate flowers. In yet another work a group of men gorge themselves on an abundance of grapes; it is strangely and attractively homoerotic.

The works in a good neighbour really benefit from the smaller and more intimate spaces provided by the Greek Primary School and Pera Museum, but the exhibition at Istanbul Modern falls flat by contrast. It is as if the aura of the white cube renders every work too monumental and too self-important. In addition, the idea of bringing what is outside in public space and in the streets, back inside the museum, usually does not work. It either becomes too literal, as is the case for Yonamine's urban collages and Alper Aydın's bulldozer blade pushing chopped trees into a corner (DM8, 2017); or too illustrative, as in Latifa Echakhch's newly commissioned Crowd Fade (2017) that depicts a protest movement as a decaying mural, alluding to the undermining of resistance and the right of assembly.

As relevant as these themes are in a Turkey where the space to voice public or civil disobedience is growing increasingly smaller, these artistic gestures are not fully convincing. What Adel Abdessemed's Cri (2013), an ivory statue of photojournalist Nick Ut's 1972 iconic photograph of a young Vietnamese naked girl running in the streets after a napalm attack, is doing in the show is anyone's guess. Similarly, Xiao Yu's durational performance Ground (2104/2017) involving a donkey ploughing a makeshift field next to Istanbul Modern's entrance feels uncomfortably misplaced. For a biennial that derives its political strength from its spatial poetics, as do its artists, this is unfortunate.

Volkan Aslan's newly commissioned three-channel video Home Sweet Home (2017) is an exception at Istanbul Modern. It is a thoughtful and ruminative piece that shows two women, one on the left screen and one on the right screen, going around their daily business: drying and brushing hair, tending to a plant, making coffee. One woman is seen in a living room, the other one on the deck of a boat. The middle screen functions as a separator and a connector showing us water and the shoreline. The sedentary shelter of a home is pitted against migratory existence, perhaps one of displacement. In a Turkish, but also in larger Mediterranean context, the sea is no longer an innocent body of water or a place of travel and leisure, rather it has become an exit route, the beginning of a perilous journey, and potentially a graveyard. Towards the end these seemingly disparate images come together, both women are actually on the same boat-home, a small house perched on the vessel.

The notion of home as an expansive thread that pulls so much of this exhibition together also ties into the spaces the 15th Istanbul Biennial has occupied as 'houses' in their own right, like a school, villa, and museum. The most poignant example of institutional critique at Pera Museum, for example, is found in Fred Wilson's extensive installation Afro Kismet (2017), in which works borrowed from Turkish museum collections, Istanbul shops, as well as newly commissioned Ottoman miniatures and other pieces make visible the role of black people in the Ottoman Empire. By ingeniously intervening in how the artworks are displayed, Wilson brings the role of Afro-Turks to the foreground and insists on their historical presence, rather than turning them into an oft-ignored historical footnote. For example, a series of drawings is covered with tracing paper, but the black characters' faces are cut out. In large paintings of battles and lush interiors, the faces of black warriors, musicians and servants are enlarged and placed next to the painting, literally taking them out of subservient roles and providing them with individual subjectivity. An Ottoman miniature shows a white subject bowing to a black king; another miniature shows a boat filled with black merchants. The decolonisation of museums is a hot and timely topic, which Wilson addresses imaginatively and gracefully.

Mahmoud Khaled's Proposal for a House Museum of an Unknown Crying Man (2017), which occupies all floors of the villa of ARK Kültür cultural space in the lively neighbourhood of Cihangir, also deserves special mention. Conceived as a fictional museum, the audience enters with an audio guide and discovers that the absent inhabitant of the house is an Egyptian man who moved from Cairo to Istanbul a decade ago. A narrative of queer persecution in Egypt and later in Istanbul is told through this unknown man's belongings. Contextual references are drip-fed throughout the tour: the arrest of 52 men on a gay disco boat on the Nile in 2001, photos of cruising areas, a disturbing excerpt of Egyptian director's Maher Sabry's film All My Life (2008) in which a gay man is being tricked into an arrest, and a leather jacket typical of what the mukhabarat (Egyptian secret service) might wear, to name a few. Jacques Brel's classic song 'Ne Me Quitte Pas', a tale of love lost, resonates throughout the house. Khaled's piece is gripping and the format of the museum works exceptionally well to keep the memory of this unknown crying man, and so many others with him, alive. It also operates as an ominous foreboding, if not warning, for the threatened position of LGBTQI communities in contemporary Turkey, who face increasing harassment and abuse due to growing conservatism in the country. A threat that the art world, too, is grappling with, if events in recent years have shown, including attacks on galleries—and one assassination at an exhibition opening.

Following Khaled's installation, then, we might ask: Is a good neighbour an absent one? International attendance during the preview days seemed quite low compared to previous editions of the Istanbul Biennial, which has long been feted as one of the art world's most important exhibitions of its kind. Whether this is a matter of biennial fatigue, jitteriness because of terrorist attacks or Turkey's authoritarian politics is up for debate, but what is unquestionable is the need now more than ever for the international art community to take on the role of good neighbour to the Turkish art scene, as it navigates what are changeable and challenging times. In this respect, we should read Elmgreen & Dragset's curatorial premise not merely as a question, but rather as a soft yet urgent plea for solidarity. —[O]