In Alberto Burri's sculptural paintings, materials are destroyed, degraded, and transformed into potent visions of decay.

Read MoreBurri was born in Città di Castello, a small town in the Umbria region of Italy. He initially studied as a doctor, graduating from medical school in 1940—in the same year, two days after Italy's entrance into World War II, Burri was sent to Libya as a combat medic. In May 1943, he was captured in Tunisia and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Hereford, Texas. Liberated in 1946, Burri was repatriated to Rome and began his painting career. He married Minsa Craig, an American dancer and choreographer in 1955, and wintered in Los Angeles with her from 1963 to 1991. Just before his death on 13 February 1995, the artist was inducted into the Legion of Honour and awarded the title Order of Merit of the Italian Republic.

Alberto Burri set the stage for the radical Italian Arte Povera movement, exploring the brutal transformation of matter through painterly experimentation.

Burri began painting in 1944 in a Texas prisoner-of-war camp, where he turned his surgeon skills toward artmaking. Using the limited materials available at the camp, Burri sewed together scraps of cloth, burlap, and discarded materials, splashing these rags in red paint to simulate bloody bandages. The violence and poverty of his war experiences would directly influence his artistic process. What followed would be a five-decade exploration of creative destruction, with Burri pioneering a range of experimental processes.

In the mid-20th century, Burri experimented with unusual pigments and resins, creating his 'Muffe' (Molds) (1951—1953), 'Catrami' (Tars) (1948—1952), and 'Gobbi' (Hunchbacks) (1950—1955). All three types of works share distinct formal properties, including blocky collages of different materials, wound-like punctures in the layered surfaces of the canvas, and traces of destructive processes like burning, stress cracking, or decay. The abstract compositions combine painting and sculpture with destructive materiality, creating abject surfaces that are trapped in an eternal state of deterioration.

His 'Sacchi' (1950—1956) series uses scraps of burlap stitched together into seemingly rotting, abstract surfaces. Burri often bordered the dirty browns of burlap with flat rectangles of thick paint, bringing the material degradation of the sacking into sharp relief. The relief-like quality of his 'Gobbi' series, where inserted invisible objects poke the canvas out from behind, is also emphasised in his 'Ferri' (Irons) (1958—1961). In this series, sheets of tarnished metal are pinned or spot-welded together, creating a patchwork of crumpled metal scraps that buckle outwards, as if from some mysterious impact.

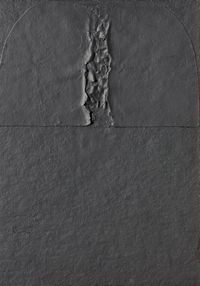

Perhaps influenced by American Minimalism, Burri's 'Combustione' (1950—1968) and 'Cretti' (1958—1979) works focus on simple material actions and monochromatic palettes. Most of his 'Combustione' are layered compositions of paper, metal, or plastic sheets that have been variously burned. The charred holes left behind induce a skin-like effect, with blackened cavities punched out of the surface that reveal the blank supporting structure behind.

The tautness of these surfaces is released in Burri's 'Cretti'. Responding to the desiccated land of his yearly visits to Death Valley, Los Angeles, the artist created simple rectangles of craquelure, a fracturing of the paint surface. He achieved this effect by combining zinc white pigment with PVA (polyvinyl acetate) to create radiating patterns of fissures, mimicking the parched surfaces of desertscapes. The vision of his 'Cretti' would be realised on a massive scale with Cretto di Burri, a monumental land art project begun in 1984 but left unfinished in 1989. Completed posthumously in 2015, Burri coated the ruins of the small town of Gibellina in Sicily with white concrete, resulting in a labyrinth of cracks big enough to walk through.

Burri's last series would further develop a language of formal minimalism, revisiting some of his earlier motifs with a brand of fibreboard called Celotex. In Grande nero Cellotex M 1 (1975) the black rectangle composing the work is slashed in two by subtle textural variations. The compositions in his 'Cellotex' cycles are flat and crisply delineated, only differentiated by slight differences in tone and surface, a legacy of minimalism's focused sparsity.

Throughout his lifetime, Burri was the recipient of several awards, including the UNESCO Prize at the São Paulo Biennial (1959); Critics' Prize at the Venice Biennale (1960); Premio Marzotto (1964); Grand Prize at the São Paulo Biennial (1965); Feltrinelli Prize for Graphic Art (1973). He was inducted into the Legion d'Honneur in 1993 and awarded an Italian Order of Merit (1994).

Burri's paintings haves been collected worldwide, with works in the collections of the Guggenheim Museum, New York; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Tate Modern, London; Palazzo Albizzini, Italy; Art Institute of Chicago; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires; Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium; and the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Rome.

Peter Derksen | Ocula | 2022