Huang Yong Ping

Huang Yong Ping. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels.

Huang Yong Ping. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery, New York/Brussels.

Born in 1954 in Xiamen, China, Huang Yong Ping is a performance and installation artist who emerged from the '85 New Wave: a momentous avant-garde movement that flourished across the country from 1985 to 1989.

After graduating from the Department of Oil Painting at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou (now China Academy of Art), Huang returned to his birthplace as a teacher and started organising exhibitions and events with his friends. He formed a group named Xiamen Dada in 1986, which published manifestos and staged provocative events in the vein of Dadaism in the late 1980s, and rose to prominence as a core founding member.

1989 marked a pivotal year for the serial provocateur: his participation in the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre that year at the Centre Georges Pompidou marked his first major appearance on the international stage. The June Fourth Incident in Beijing precipitated his move to Paris, where he is still based today.

The recent exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World (6 October 2017–7 January 2018), opened with numerous works by Huang dated to his early Dadaist years. The exhibition is titled after Huang's eponymous work, where a snake-like cage structure called The Bridge (1995) arches over a tortoise-like cage structure, called Theater of the World (1993).

In the original work, live snakes and turtles crawled inside the bridge, while several geckos, toads and snakes mingled with hundreds of insects in the structure beneath, which inevitably led to some devouring others. The work was vehemently protested by animal rights activists before its New York debut, who demanded 'cruelty-free exhibits' through an online petition that has gathered more than 800,000 signatures. Under unrelenting pressure and to the chagrin of free-speech defenders, the Guggenheim decided to leave out the animals.

Huang's two other works included in the exhibition, however, typifies his early approach: conceptual, gestural, and often humorous. In his canonical work The History of Chinese Painting and A concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes (1987/1993), Huang washed two art history textbooks in a washing machine as the title described and presented the product of the act—a heap of paper pulp—as the artwork.

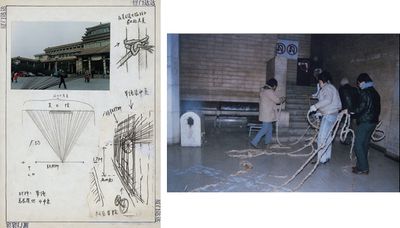

In another famous work, Towing Away the National Art Gallery (1988), a photo-collage resembling an engineer's drawing, Huang devised a plan to pull down the stately National Art Gallery in Beijing by hemp ropes attached to its Sino-Soviet façade. The proposal went unrealised but stands as a prime manifestation of the transgressive attitude of the '85 New Wave movement.

Professing an early interest in Marcel Duchamp, Huang continued to produce Duchampian provocations that often juxtaposed disparate cultural elements after he relocated to Paris. In 1997 he participated in Skulptur Projekte in Münster with the large-scale installation 100 Arms of Guanyin (1997), which was an enlarged model of Duchamp's iconic Bottle Rack (1914) that hung 50 modelled object-holding arms. The title directly references the Buddhist Goddess Guanyin, who has 1,000 hands that hold religious objects, though here the arms are commercial mannequins that hold everyday objects such as brooms and trinkets.

Another recurrent imagery that Huang used is that of the serpent. Huang's fascination with animals, especially the reptile, started as early as his first appearance in the 1989 Magiciens de la Terre exhibition, for which he presented a washed newspaper pulp installation titled Reptile (1989). His giant twisting aluminum-cast serpent skeleton situated in the Bay of Biscay, Serpent d'Océan (2012), or skeletal serpent frame weaving in and out of 305 logo-bearing shipping containers under the majestic glass dome of the Grand Palais for the 2016 edition of Monumenta, Empires (2016), among numerous others, stunned viewers with its mixture of industrial production and primal, quasi-mythological forces.

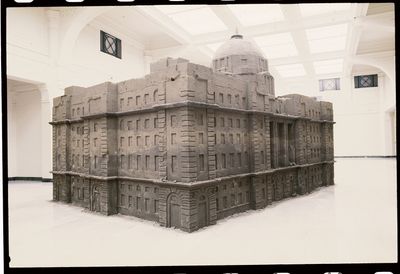

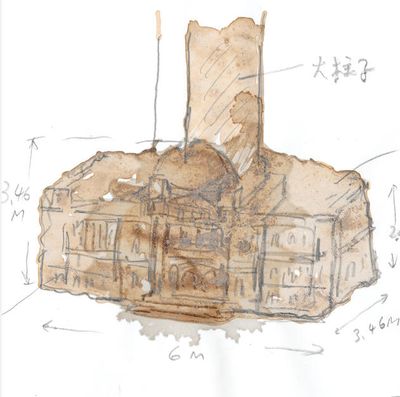

Between 28 April and 9 June 2018, Gladstone Gallery in New York is showcasing another of Huang's iconic works at their 21st Street space, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank (2000), originally commissioned for the 2000 Shanghai Biennale. Measuring 6 metres long, 4.3 metres wide and 3.5 metres high, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank was modelled after the former HSBC Building in Shanghai, a six-floor neoclassicist building that was constructed in 1923 on the Bund that was once the largest bank building in the Far East.

Huang's 'bank' is made out of dry sand mixed with a small quantity of cement poured into moulds. Though it retained a basic shape after water was sprayed on it, it was vulnerable and would slowly dissipate. While this work embodies Huang's usual combination of trenchant critique with clever choices of form and material, its re-installation in New York gains new relevance in a world with renewed disillusionment with the older socio-political structure. In this conversation, Huang reflects on his two most recent New York representations within his wider practice.

TDWhat inspired you to make Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank (2002), commissioned by the 2000 Shanghai Biennale?

HYPThat was the first project I realised in China after I left the country in 1990. 2000 marked a transition in the Shanghai Biennale's focus on international contemporary art. Among many reasons, the work's most significant inspiration was the new reality in China at the time, when the economy was booming.

The project included two works: Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank, and Hat Lampshade, which was modelled after the hexagon-shaped lampshade in the dome of the northern gate foyer in the old Shanghai Art Museum. The lampshade also echoed the shape of a hat that was popular among European colonialists between 1850 and 1940. The two works complemented each other. Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank was colossal, attractive but fragile, while Hat Lampshade was incorporated into the architectural structure and was barely noticeable.

There are a lot of connections between these works and the projects that I did in Europe in the 1990s, which dealt with colonialism, and the exhibition in Shanghai in 2000 was interpreted as a reminder of the city's colonial history. The Shanghai Art Museum was formerly the Shanghai Race Club, a horse-racing club founded by the British. But the project was in fact a discussion of current and future conditions.

Hat Lampshade references the notion that anybody can put on a hat, and the function of a hat is to change one's appearance. Colonialism is closely linked to capitalism and the market, and banks are the fulcrums around which the market moves as the lever for China's rapid development. The 2000 Shanghai Biennale presentation was an allegory of that.

TDIn its form and materials, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank seems to be a metaphor for ephemerality that acquires a critical edge when taking into account the building it depicts—the former HSBC Building in Shanghai, designed by Palmer & Turner Architects and built in 1923 by the British contractor Trollope & Colls. Could you talk about the relationship between the material form of the sculpture, and the architecture that it represents?

HYPThe HSBC Building is the most significant landmark on the Bund. Its history reflects the history of Shanghai's development. After its completion in 1923, the British called it 'the most luxurious building between the Suez Canal and the Bering Strait'. In 1949, this lavish bank was taken over by government officials. The shadow of Western capitalism completely vanished, but the building was turned into a bank again in the 1990s, when the lease was obtained by Shanghai Pudong Development Bank.

TDHow is a bank related to sand?

HYPWhen society desires a large amount of money, money is converted to sand. If the fulcrum is a bank of sand, we are crawling in sand like mice. The work's intention was to question the idea of a 'bank' as a central point that was supposed to support movements and operations, and the fact that the concept of 'bank' collapsed meant sand was the most relevant material to use.

TDHow do you control the speed at which the sand disintegrates to make the metaphor effective?

HYPWhen I was first conceiving the work, I noted that it consists of wood moulds on four fronts fixed by long screws. Dry sand mixed with a small amount of concrete is to be watered and consolidated in the moulds. After it has dried out, the 'Bank of Sand' would largely maintain its appearance, but it is fragile and temporary, with a risk of collapsing any time.

A critic responded that the work was like a sand castle in the first place, but is in the process of gradual self-deconstruction, and continues to collapse as the exhibition goes on. This imagination was of course an extension of the work. If an artwork has to 'work', then it becomes an automated puppetry installation, which is a product of complicated design.

Maybe I ought to have designed it so that the movement of one single particle would cause a section of the work to collapse, which would in turn cause the whole work to collapse—the concept of the work simply brought about this imagination, like the idea of an earthquake on the last day of the exhibition that would collapse both the pile of sand and the architecture.

TDBetween 28 April and 9 June 2018, Bank of Sand, Sand of Bank will be on view at Gladstone Gallery in New York. How do you think the work will fit into the American context, in comparison to the original context in which it was shown?

HYPBy bringing it to New York, the work is returning home: the city is the centre of Wall Street capitalism, and the Sino-American trade war is at its most intense. The work not only refers to contemporary problems in China—China's future is also merely a late-arriving America. Through total rejection or imitation the practical outcome will be the same.

The onsite construction of the original work was assisted by a construction team that was working in a building across the street from the Shanghai Art Museum. They spent two nights delivering 25 tonnes of sand into the museum—transportation of this kind could only happen at night. This kind of scenario is only possible in China.

TDYou recently participated in Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World (6 October 2017–7 January 2018) at the Guggenheim, an exhibition that was actually named after your 1993 work, Theater of the World, which consisted of a cage designed to house reptiles and insects. The work was left empty for the show, as a result of pressure from animal rights protestors. In response to the controversy, you mentioned that Theater of the World has been censored multiple times in the past, from Paris to Vancouver. Was the potential for censorship a part of the work's conceptual framework? Was the opposition you experienced in New York any different to what you have encountered before?

HYPFirst of all, I do not predetermine the work's audience. How can an artwork be created just to be censored? I am also against the idea of provocation for its own sake. This has to do with the teleological aspect of a work, I advocate for an art form that is aimless.

Theater of the World was made in 1993 at the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany. The academy invited artists to work as residents in independent studios, and the work's structure resembles those tiny cabinets in which artists were compartmentalised like insects, in close proximity to one another. I started using live animals that year.

I wanted to use lions from a zoo for an exhibition in Glasgow, but the exhibition was in vain. It was less about censorship and more about unsuccessful negotiations. For an exhibition in Oxford, I used one thousand live grasshoppers and five scorpions. I was told that the exhibition was considered controversial but it was not extremely serious. When Theater of the World was exhibited at the Akademie Schloss Solitude, it received 50 to 60 viewers at most.

Censorship often has to do with the location and the scale of the exhibition, so an exhibition that is unknown to the public kind of enters self-censorship, or it might merely be at a time when the work has not yet developed. Censorship comes in all forms, it can be political or religious. Sometimes it is translated into budget and safety reasons, sometimes it is initiated by the museum, the curator or the public. The public in turn needs media and press, and the recent censorship in New York was a totally new kind that happened in the realm of the social network.

TDThe Guggenheim exhibition also showed fascinating sketches for Theater of the World. How would you describe the role of sketching in your creative processes? Even though many of these seem to be spontaneous—such as sketch for Large Turntable with Four Wheels (1987), which is written on found paper with a middle school's letterhead—they are exquisitely rendered and often contain the works' conceptual core. Is it accurate to say that you made use of sketches more frequently in your earlier career?

HYPIn my practice, sketching and studies are the 'remains' or the 'residues' of a work. Remains could be considered as the excess of energy and work, from which the work itself is formed. Studies sit between 'residues' and 'waste', including sketches or detailed plans, or large piles of used papers.

You could say that my studies are manual pages—a collection of the 'residues', which include the origin of the work, as well as its references, detours and processes. It lies in between album, manuscript, and memorandum.

TDTowards the end of the 1980s, you constructed many objects that had a crude yet enigmatic appearance, such as Big Roulette (1987)—a Duchampian combination of a readymade table-like structure with a roulette spinner. When working on these objects, are you trying to push the viewer to respond to the concept of the piece rather than its aesthetics?

HYPThe 1980s in China were marked by poverty. Pretty or nice looking things and objects were scarce. My solution was to obtain what was at hand. Those things turned out to be the best, and coincidentally the most conceptual.

TDYou have referred to the influence of Rauschenberg in your process of 'trying to transcend traditional painting'. This urge to 'transcend' characterises your early works, such as Burning Event (1986), which saw you and other Xiamen Dadaists burn your paintings outside the Xiamen Art Museum. Would it be accurate to say that your later works no longer depart from the transcendence or destruction of something as frequently as your early works?

HYPPerhaps. Everyone has to start by 'going beyond' a certain event or matter to create an illusion of progress or development, but gradually the artist will have to start anew by going beyond himself or herself. You cannot immolate yourself like a Vietnamese monk, and art is not afraid of illusions. Art reaches the truth via illusions, if the truth indeed existed.

TDThe '85 New Wave had so much oppositional energy. In Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, we find institutional opposition in Towing Away the National Gallery (1988), and in a work by your contemporary Wang Guangyi titled Mao Zedong: Red Grid No. 2 (1988), which depicts a portrait of Chairman Mao superimposed by red grids as if behind bars.

Usually, an institutional system needs to be fairly established before avant-garde movements are able to forge an anti-institutional path. China had only just emerged from the ravages of the Cultural Revolution when the '85 New Wave became active, at a time when China's art infrastructure was far from being established. What caused such institutional resistance among your generation of artists?

HYPYou have a point. It has been 30 years since I did the Towing Away the National Gallery project. The museum is still there, unchanged, and I have never wanted to step inside it in 30 years. Regarding rebellion or resistance, maybe these could be better understood in terms of Chinese phrenology: some people are born with a reverse bone—a sign of rebellion or resistance. —[O]