Joan Kee on Tansaekhwa

Joan Kee has written a seminal book entitled Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method. The book considers Tansaekhwa, one of the most important artistic movements in contemporary art history—yet one that has been significantly over-looked.

Tansaekhwa, or Korean monochromatic painting, references a loose grouping of Korean artists who, starting in the mid 1960s, started to manipulate the materials of painting to create mostly large abstract paintings executed in white, black, brown, and other neutral colours.

During the 1970s and 80s, works by artists such as Park Seo-Bo, Ha Chong-Hyun, Kwon Young-Woo and Lee Ufan, came to be seen by critics, curators and artists as representing contemporary Korean art, and more widely contemporary Asian art. Kee's book provides an informative and clear explanation for the context and characteristics that define Tansaekhwa; but equally it encourages further investigation of this intriguing and important facet of art history.

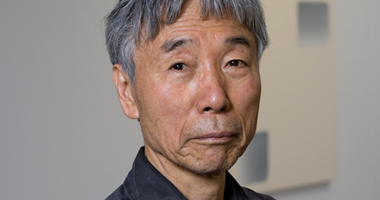

Joan Kee holds the first university position in North America specifically created for the study of modern and contemporary art in Asia. Kee is an assistant professor of art history at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Since the late 1990s, she has written widely on East and Southeast Asian art for such publications as Artforum, Art Bulletin, Art History, Oxford Art Journal, Third Text, and the catalogue for the Korean Pavilion at the 50th Venice Biennale.

Histories of contemporary art in turn have ascribed to artists and artworks the role of victim: what has the law done to art, or rather, what has the law not done to art?

ADFirst, before we start discussing the book, a bit about you. You originally set out to be a lawyer and in fact hold a degree from Harvard Law School - but you then decided to study art history and earned a PhD in art history from NYU. Why the change of direction?

JKMy undergraduate degree is in art history and I had always meant to pursue an academic career in the field; however, one of my university professors very wisely pointed out that it was perhaps a good thing to work for a while in an entirely different field. The inherently interdisciplinary nature of law offered a lot of different ways of thinking about various subjects and how those subjects relate to one another. In many ways, the study of law is about spotting narrative gaps, contradictions, and logical inconsistencies that are central to how we understand a particular subject.

ADYou have a second book project underway already and I understand its provisionally titled What Art Has To Say About The Law. So this will be a literary meeting of your legal experience and your art historical study?

JKIt was brought about by a desire to think of how art history and legal studies play off of each other in mutually productive ways. Legal studies overwhelmingly treat the art-law relationship as a function of selling, buying, creating and exhibiting artworks. Histories of contemporary art in turn have ascribed to artists and artworks the role of victim: what has the law done to art, or rather, what has the law not done to art?

Inherent in these studies is a tendency to insist that artworks contain some kind of hidden meaning, an assumption leading viewers to erroneously, or even wrongfully assign to artists motives unsupported by the actual experience of interacting with a particular work. Analogous is the tendency of many histories of modern and contemporary art to treat the law as a monolithic apparatus of control often complicit with an ethically questionable politics. Such assumptions ignore the matrix of contradictions, debates, and processes by which laws are made, exercised, and changed.

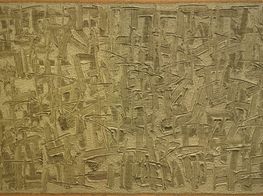

My first book actually helped me start thinking more intensively about the art-law relationship as a large part of it concerns how artists living under martial law in 1970s Korea used materials to compromise, or otherwise elude the restrictions and demands imposed on culture by an authoritarian state. I argued that they were able to work with and beyond numerous limitations on the freedoms of expression and assembly at that time because of their understanding of painting and the kinds of demands it made of its viewers.

The current project on art and law looks at the relationship between law and visual art is a primary example of the fundamental tensions defining society, particularly in the U.S. from the early 1970s to the late 1980s. During this time, courts intensified their scrutiny of artistic content while the so-called "culture wars" of the Reagan years saw radical changes in legal doctrines of property, contract, and definitions of identity. The magnitude and speed at which these changes took place instilled in many artists a sense of obligation to respond the force and scale of law's operation.

What these responses were will make up a large portion of the new book; another portion will look at how methods used in humanistic disciplines productively affect other systems of thinking in ways that directly benefit society at large. How does the experience of interacting with these works enable the possibility of imagining more concretely the links between the built environment, politics, and material forms in ways that offer us ways of thinking what obligations must be fulfilled to better achieve a more just society?

One of the major dimensions of this contribution is how certain Tansaekhwa artists grapple with the particular challenges set forth from having been trained in ink painting.

ADYour current book looks at Tansaekhwa - the first contemporary Korean artistic movement to be actively promoted internationally. When and why did you decide to write a book on this subject?

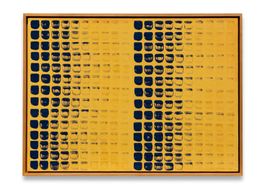

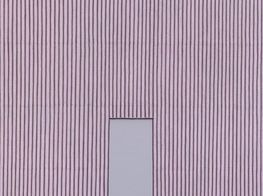

JKFirst and foremost, that they are intriguing works that represent a major contribution to an expanded history of abstraction. One of the major dimensions of this contribution is how certain Tansaekhwa artists grapple with the particular challenges set forth from having been trained in ink painting. Take for example, work by Kwon Young-woo, who was among the first postwar Korean artists to major in ink painting at university.

Some time in the early 1960s, he decided to get rid of his ink and brush and instead use his fingernails, palms, and even elbows to tear directly into the paper used for traditional ink painting—the result is something akin to process-based works in the West, but at the same time utterly different. Another example is Lee Ufan, who paints using mineral pigments ordinarily found in 'Japanese painting' as well as canvas—an unusual combination of materials that raise the issue of so-called traditional media's place in contemporary art.

ADThis title of the book references the phrase "the urgency of method". Perhaps you could discuss the reference to 'method' as a means of explaining the movement?

JKThe works of artists like Lee Ufan, Kwon Young-Woo, Yun Hyong-keun, and Ha Chong-Hyun foregrounded contemporary art as an idea fundamentally based on a series of beliefs and doubts concerning the role of medium and the viability of notions like tradition and cultural difference. Their promotion as the face of contemporary Korean art in the late 1970s and 1980s also emphasizes the degree to which the idea of 'contemporary Korean art' is itself a method, a means of responding to an international art world based on the recognition of discrete national and cultural differences.

Whatever the personal and political antipathies of their makers, the works that comprise some of Tansaekhwa's most representative examples highlight questions ignored, neglected, or even actively suppressed in mainstream Euromerican histories of postwar art. It raises, for instance, the curious position of ink painting—for artists like Kwon Young-Woo and Lee Ufan, ink painting was both an ongoing legacy and a renewable source of material challenges that urged them to more vigorously push the question of abstraction. Such explorations continue to resonate today, as international contemporary art has paradoxically revealed itself to be both more expansive and less inclusive than ever before.

It's not surprising, then, that Tansaekhwa's emergence coincided with the frequency with which the word method, or in Korean (pangbŏp) was used in Korean art criticism during the 1970s and early 1980s. The term first surfaced in the late 1950s, not long after critics like Pang Keun-t'aek and Kim Yŏng-ju tried to puzzle out what a distinctly modern, postwar Korean art might entail. Method was widely circulated, however, in relation to the series of Seoul Method exhibitions that took place from 1977, and which involved a sometimes bafflingly diverse array of artists, from Kwon Young-woo to conceptual artists like Lee Kun-yong.

As one of the exhibition series founders, Lee stated that "for an artist to have his or her own method is a question of that artist's attitude and language." In one sense, method was thus a call for artists to develop their own approaches in the vacuum of the late 1970s created by the increasing irrelevance of the government-run national salon, the Kukjŏn, as a leading venue for contemporary art, the rise of artists interested in media other than painting and sculpture, and the continuing need to think about the position of art amidst the pressures of so-called "everyday life."

Other artists involved with the Method exhibitions regarded the call to individuation as a push-back against what they saw as the reductive, non-pluralistic tendencies of contemporary Korean art. Above all, the question of method, as described in a 1980 edition of the Seoul Method show, meant having to answer the question "what does our time demand of us?"

The word "method" also brought to the fore questions of interpretation with which critics grappled in the early 1970s, when the international circulation of Korean art, particularly in Japan, posed its own set of challenges. As the first deliberate attempt to brand a distinct identity for contemporary Korean art for international audiences, the story of Tansaekhwa's emergence forces us to ask questions of "why" and "how": it is a near certainty that the current wave of international interest in contemporary Korean art will soon fade into comparative indifference unless a case can be made as to why this art matters to the construction of a world art history.

The most pressing task lies not in enumerating artworks, individuals, and events, but in outlining the main streams of identification and belief on which the idea of contemporary Korean art depends. That contemporary Korean art should matter, particularly to non-Korean audiences, is most apparent when we regard not only its subjects, but also the idea itself as a method for thinking about one's place in the world.

On the one hand, certain formal comparisons make it easier to decouple Tansaekhwa works from the rhetorical ends to which they were put in the late 1970s and to relate them instead to a much broader conversation on abstraction.

ADThe importance of Japan to the movement is expressed in the book. I noted that Lee Ufan, whose work is referenced on the front cover, spent much of his time there. Why was there this Japanese engagement with the movement?

JKMainly because Japan, for most Korean artists, was the nearest and most feasible point of access into the international art world after the re-establishment of diplomatic ties between South Korea and Japan in 1965. We're talking about a generation that was born during Japan's occupation of Korea, who were largely fluent in Japanese and acquainted with Japan's artistic infrastructure. A key player in facilitating this engagement was Lee Ufan, whom many artists credit with helping them show their works in Tokyo.

Many Japanese critics and gallerists in their turn saw Tansaekhwa as a useful means of visualizing what they referred to as a discrete "Asian" contemporary art, something I talk about in the book's fifth chapter. Indeed, one of the most important exhibitions of Tansaekhwa,Five Korean Artists, Five Kinds of White at the Tokyo Gallery, was conceived as part of a larger "Asian art" series by the gallery's owner, Yamamoto Takashi. Another point of contact is with Taiwan; in 1977, a large exhibition of Korean painting featuring many examples of Tansaekhwa took place at the National History Museum in Taipei. The reception of this exhibition suggests future possibilities for thinking about an interregional history of abstraction.

ADWhat relationship is there between Tansaekhwa and Western art movements of the same period?

JKThere are a lot of "false friend" parallels, some of which were based in Tansaekhwa artists actually having seen certain works, such as Yun Hyong-keun having seen and admired the works of Mark Rothko. I'm also intrigued with some of the affinities between the works of artists like Ha Chong-Hyun and Hélio Oiticica, a Brazilian artist who grappled with the ambiguous separation between two- and three-dimensionality, or regional patterns of circulation through which the idea of abstract ink painting could be viewed; e.g., tracing lines of affiliation between the Filipino artist Fernando Zóbel, the Taiwanese artist Fong Chung-Ray and Kwon Young-Woo.

Such resemblances bring us to the heart of what has been pointed out about Korean, or for that matter, many examples of non-Western, art, that the question of whether to keep or omit one-to-one comparisons between Western and Korean works "stands at the heart" of how to think about modern and contemporary Korean art. On the one hand, certain formal comparisons make it easier to decouple Tansaekhwa works from the rhetorical ends to which they were put in the late 1970s and to relate them instead to a much broader conversation on abstraction. This has the potential of introducing foreign audiences to a more pluralised view of abstraction based on how Tansaekhwa both resembles and diverges from its counterparts elsewhere.

Tansaekhwa works shifted the burden of figuring out what's going on onto the viewer, and in so doing, reconfirmed that you were indeed in possession of your own senses

ADAn extract I read in relation to the book stated: "Tansaekhwa made a case for abstraction as a way for viewers to engage productively with the world and its systems." Perhaps you could expand on this?

JKOne example is to look at various examples of Tansaekhwa through the politics of its time, which in the early 1970s was significantly inflected by the declaration of martial law in South Korea in 1972. Present histories of Korean art misread Tansaekhwa's fidelity to materials as apolitical. Yet for Tansaekhwa artists to really interrogate the idea of painting was quite a radical thing to do if we remember how so many artists in this authoritarian era bought into representation by doing everything they could to forget that they were, in fact, painters—nothing more, nothing less.

Tansaekhwa artists were quite transparent about the scope of action—it was both defined and enabled by the limitations of the painting medium. Protest was never the main point. Nor was it mere production. But by making the process of execution so utterly, even viscerally transparent, Tansaekhwa works shifted the burden of figuring out what's going on onto the viewer, and in so doing, reconfirmed that you were indeed in possession of your own senses—this was quite an important thing to reconfirm in a deeply authoritarian, repressive era that seemed defined by a state bent on taking everything away from you. It is this reaffirmation of the viewer that made Tansaekhwa political in a time when merely walking slowly through city streets might land you in jail (a point vividly made in 1970 by the collective, The Fourth Group, when some of its members carried a coffin in a slow processional in downtown Seoul).

ADThere seems to be an enormous gap between the amount of art being produced in Korea and the numbers of art history texts and departments on Korean art. How difficult was it to research the book?

JKVery. There's a lot of really insightful, important criticism but relatively few systematic efforts at historicisation. The one exception was the mid-to-late 1970s when you had a spate of efforts to track a history of contemporary Korean art; a notable instance was Kim Yun-su's History of Contemporary Korean Painting. Published in 1975, it's a proto-revisionist history of modern Korean painting which tried to explicitly track and evaluate art according to socio-political phenomena.

More recent scholars have stepped in to fill the gap, and since the early 2000s there's been a very welcome interest in oral history—welcome, since most of the key players of the Korean art world in the 1950s-1970s are or were in their 70s and 80s. Yet we need a lot more. It's a race against the clock in many ways. In addition, writing history means much more than gathering relevant factual material. It also demands more than simply putting events in a linear sequence or even about inclusion for the sake of upholding the myth of an expanding art world. The choices made in even the most trivial-seeming acts of interpretation reflect our assumptions about art and its potential for action. Starting points, for example, are crucial.

To begin a survey of modern Korean art from 1910, for instance, is to risk having non-Korean readers overlook the particular conditions of modernity in Korea, conditions which far predate Japanese occupation and which can be traced to the mid-to-late 18th century where artists like Kang Se-hwang took as their subject the idea of what it meant to be present, or in short, contemporaneous with one's own time. Other suggested points of origin include 1953, which leads to a different kind of postwar narrative than has been otherwise assumed in Euroamerican studies of "postwar art," yet this too risks positioning art as symptomatic, rather than generative, of its context. Possibly a more useful beginning is to start with a close reading of a single work. This would opens up the possibility of constructive failure, in which the impossibility of fully accounting for this work provokes the reader to envision other ways of interpretation, other points of access.

Image searching is going to be a gamechanger for research as will be the current interest in tracking networks of affiliations; already it's possible to download large data sets and then track which institutions, events, and individuals actually exerted real impact by looking at both the number and the strength of those connections.

Part of the difficulty is the absence of courses devoted to modern and contemporary Korean art, even at the most elite institutions. It's absolutely shocking that the national flagship university in Korea (Seoul National University) has not filled the spots left vacant by Kim Youngna and Chung Hyung-min after they assumed the directorships of the National Museum of Korea and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, respectively. Of course, the teaching of modern/contemporary Western art is implicitly regarded as a priority. One only imagines the uproar in the West if, say, a major university in the U.S. were to lack an Americanist.

The problem with this lack is that it affects the kind of writing that gets produced; there's a lot of writing now, but very little is historically informed, which compromises the ability of critics to give useful feedback to younger artists. Small wonder that museum curators and gallerists often complain of a dearth of good younger artists—there needs to be critical feedback for artists and having some understanding of how works now resonate with what's been done previously is an important step.

Many histories of 20th century Korean art lack citations, bibliographies or other scholarly apparatus which can make it difficult to fact-check or cross-reference claims and observations. I ended up creating for myself a searchable database that consisted not only of newspaper and journal articles from roughly 1953 to the present but also images from the National Archives of Korea—luckily, the software for searching image databases is getting better every day.

Image searching is going to be a gamechanger for research as will be the current interest in tracking networks of affiliations; already it's possible to download large data sets and then track which institutions, events, and individuals actually exerted real impact by looking at both the number and the strength of those connections. As the book reflects, the resulting story is sometimes far different than what's being told in received histories.

One of the great strengths of Tansaekhwa and other key movements is how the task of its historicisation calls us to restructure a world art history beyond the dichotomies of nationalism and internationalism, center and periphery, or the global and local. Making good on this potential is the next step.

ADHow much does 'nation' over 'idea' hinder the promotion of Korean art?

JKIronically, the biggest obstacle in the promotion of Korean art is the endless insistence on putting the 'Korean' before the art. I hear again and again from senior scholars well acquainted with Korea and from newcomers alike that this emphasis often comes across as a kind of institutionalised insecurity. The new Seoul branch of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art will be a crucial opportunity to reframe a history of modern and contemporary Korean art in such a way that emphasises what might be called the obstinacy of art.

The works might look similar to their counterparts in the West or in the rest of Asia but when juxtaposed with certain other works can produce very intense experiences of estrangement through which we really have to rethink what we know of movements like abstraction or genres like portraiture.

The geopolitics of Korea strongly suggest that Korean art (and culture, for that matter) will always be discussed in relation to the art of somewhere else. For decades critics struggled against this, albeit by pinning their hopes to arbitrary discourses of Koreanness that ironically stifled more productive kinds of discussion. Yet one of the great strengths of Tansaekhwa and other key movements is how the task of its historicisation calls us to restructure a world art history beyond the dichotomies of nationalism and internationalism, center and periphery, or the global and local. Making good on this potential is the next step.

ADWhat do you hope the book will be a catalyst for?

JKIt's my express hope that the book would appeal to readers who are non-specialists in Asian art. I'm also hoping to see more studies on modern and contemporary Asian art that pay extensive attention to the artwork.

In terms of reception so far, I've been intrigued by the frequency with which Korean interviewers (either based in Korea or elsewhere) have asked about what I think might be done to promote Korean arts and culture overseas. My take is that contemporary Korean art is not yet 'global' until overseas institutions organize exhibitions of such art without heavy subsidies from Korean state agencies or Korean companies. Along the same lines, can there be an exhibition of postwar or contemporary Korean art without having the theme of national identity foreground the works on display?

One of the reasons I wrote this book was because I believe that many examples of Tansaekhwa deserve recognition that isn't essentially bought for them by Korean sources. Fortunately others seem to agree as seen by the growing number of non-Korean institutions and galleries interested in collecting or exhibiting Tansaekhwa works.

Even today Tansaekhwa is discussed as "Korean minimalism" despite the fact that Minimalism had almost minimal (pun intended!) impact on the postwar Korean art world and was frequently criticized by art critics in Korea the 1960s and 70s.

ADWhat other developments would you like to see?

JKA huge priority is to invest in the development of archives and translators. I could not have written this book without the resources of the Leeum archive of Korean art or that of Kim Dal-jin, who has spent most of his life gathering materials that would have probably otherwise been lost. With the exception of a very small handful of individuals, Korean-to-English translation in the arts is abysmal. And it really has a negative impact on the promotion of this kind of art, not only for non-Korean speaking researchers but for museum collections and courses, many of which are based on histories riddled with glaring inaccuracies.

One of the greatest challenges in writing the book was to double-check basic facts like names, dimensions, dates, titles and the like. At present, the majority of histories of contemporary Korean art comprise a kind of system of misdirection in which inaccuracies and generalisations are repeated to the point where they harden into a consensus that is very, very difficult to budge. For example, even today Tansaekhwa is discussed as "Korean minimalism" despite the fact that Minimalism had almost minimal (pun intended!) impact on the postwar Korean art world and was frequently criticised by art critics in Korea the 1960s and 70s.

ADWill we see an exhibition relevant to this book?

JKI'm curating a large-scale exhibition on Tansaekhwa that will open in the fall of 2014 in Los Angeles. Details regarding the venue and dates will soon be released, but it will be the first major show of Tansaekhwa in the U.S., consisting of both works that have never been exhibited outside of Korea and those that were showcased in such seminal exhibitions as Facet of Contemporary Korean Art held in 1977 in Tokyo.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a scholarly book-length catalogue featuring not only an essay, but English translations of key artist interviews as well as numerous archival images that supplement what's in the book. There is also a strong possibility that many of the works will make their way to Hong Kong as part of a larger show on postwar Korean art. —[O]