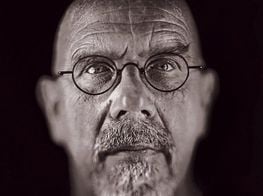

Matthew Armstrong on Collector Donald B. Marron

Matthew Armstrong before an artwork by Jack Whitten at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles, 2018. Photo: Amanda Stoffel.

Matthew Armstrong before an artwork by Jack Whitten at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles, 2018. Photo: Amanda Stoffel.

Private curator to financier and collector Donald B. Marron for over two decades, Matthew Armstrong helped shape some of the most important private collections of 20th- and 21st-century American art. Armstrong discusses working with Marron, reminiscing on the boyish enthusiasm Marron exuded when it came to art.

Armstrong and Marron first met at an auction preview, with Armstrong describing himself as 'a graduate student in a dirty sweater' and Marron as an 'exceptionally tall, rather shy man', who asked him his opinion on a Joan Miró painting. However, it was not until the Christmas party for New York's Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where Armstrong was working part-time, that he became aware that this unassuming gentleman was not only the president of MoMA's board—a role that Marron continued to hold until 1991, when he was given the title of president emeritus—but also one of New York's best-known collectors.

By the time the two first met, Marron had already amassed a significant personal collection for his home, and in his capacity as chairman and chief executive officer of PaineWebber, had begun to pioneer a new standard for corporate collecting. Drawing his passion for art into his corporate life, Marron presided over the acquisition of more than 850 works for the firm's art collection. In 1995, Armstrong applied for and got the role of curator for the PaineWebber Art Collection, formalising a relationship that would evolve with Marron's own professional progressions over the next 25 years and more.

In July 2000, PaineWebber was bought by the Swiss bank UBS and Marron became chairman of UBS Americas. Following the merger, the PaineWebber Art Collection was incorporated into the UBS Art Collection, with Armstrong continuing as its curator. In 2002, more than 40 works from the UBS Art Collection were gifted to MoMA and presented in Contemporary Voices: Works from The UBS Art Collection (2005). The exhibition spoke to the calibre of art that had been acquired for the collection, featuring works by artists such as Cy Twombly, Philip Guston, Brice Marden, Willem de Kooning, and Jenny Holzer.

In 2003, Marron and Armstrong both stepped away from UBS, and Armstrong took on the role of curating the art collection of Marron's private equity firm, Lightyear Capital, while continuing to advise him on his personal collection. In 2018, the public were given the opportunity to see some of the works from Marron's collection when it went on display in the Fuller Building in Manhattan. It was an exhibition that Armstrong describes as very much reflecting the sensibility of Don's personal collection, such that 'you are immediately struck by the vivid colours, and the physicality of the constructions'.

In 2019, Marron unexpectedly passed away, and soon after auction houses began to compete for the Donald B. Marron Family Collection. It was subsequently reported however that powerhouse galleries Pace, Acquavella, and Gagosian would sell around 300 of the works—estimated by some sources to be worth over USD450 million. It was a move that surprised the art world, but not Armstrong, who described it as reflecting the friendships Marron had built with Arne Glimcher, William Acquavella, and Larry Gagosian, over many years.

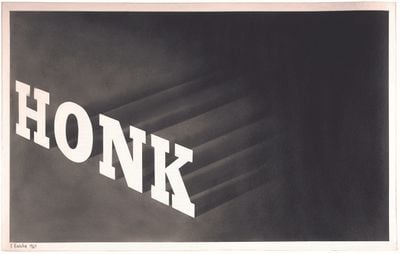

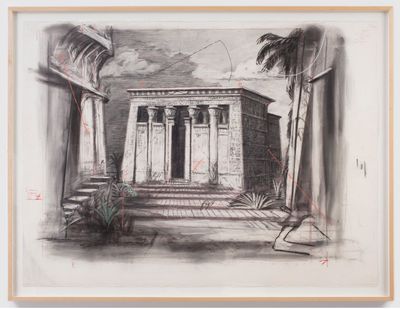

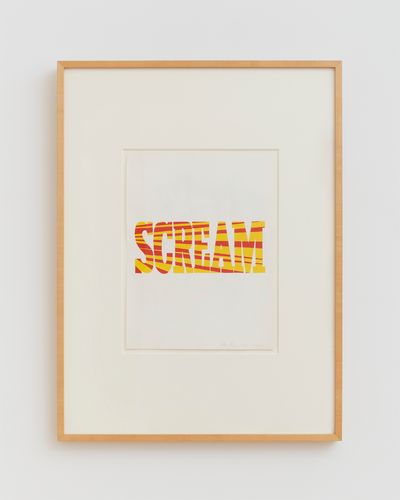

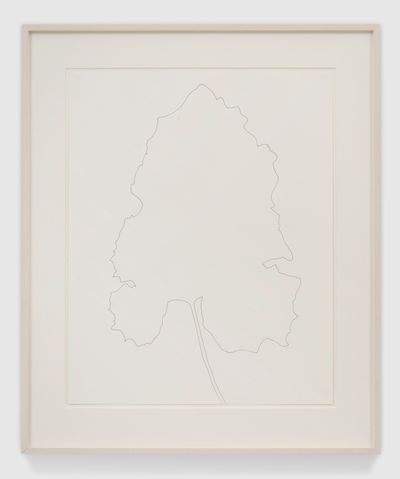

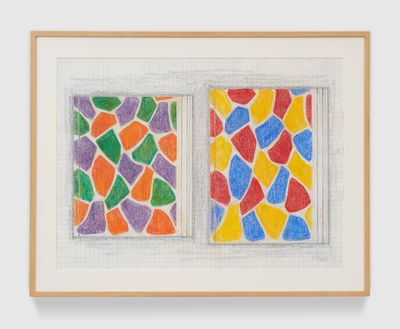

Works on Paper from a Distinguished Private Collection, an exhibition of drawings from the Donald B. Marron Family Collection presented by the three galleries, is showing at Pace Gallery's newly opened branch in East Hampton, New York, between 12 and 20 August 2020. The exhibition features an intimate presentation of almost 40 works on paper, many of which are being exhibited for the first time since their acquisition. Works on view range from early modern masterpieces by Henri Matisse, to nature studies by Ellsworth Kelly, and contemporary art pieces by Mamma Andersson and Brice Marden, among others. Also to be included in the exhibition is a spotlight on Ed Ruscha's typographic and image-based drawings, including early language-based artworks such as Honk (1964), Red Yellow Scream (1964), and Holloween (1977).

In 2021, the three galleries will present a major joint exhibition in New York City showcasing the breadth of the Marron Family Collection. As Armstrong notes in this interview, it is his hope that such an exhibition will reflect Marron's sensibility as it 'developed, enlarged, contracted, and expanded—to show how he reached back, how he looked forward, what he collected recently, what he collected years ago, and how he was frequently ahead of the curve.'

ADWhat influenced your decision to work in art?

MAI was fortunate to have parents with an avid interest in culture, spanning literature, history, art, and music. I grew up in a family that spent time at art museums and concert halls. I vividly remember seeing in a single day, landscape paintings by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, soap boxes by Andy Warhol, and Leonardo da Vinci drawings. At the age of nine or ten, I remember seeing a show of works by Alberto Burri, who I still love. We were encouraged to imbibe as much art as possible.

I remember asking Don early on what it was, exactly, he wanted me to find. And he said, 'Your job is to find me the best art.'

When I went to university and took an introductory course to art history, the lecturer flashed an image of a surrealist Picasso next to an image of the Venus of Willendorf on the screen, and asked why we thought people felt the need to make art. I knew I was in the right place; thinking about art had always been part of my world.

ADWhen you look back on your early art education, do you see any singular shift in the experience of contemporary art today?

MAAs a student I was encouraged to think canonically, with a focus on the great pictures of the West and East: the great totemic constructions that led one to religious thoughts or narratives, or affirmations of power. There was a set way to experience art. Today, we are confronted with billions of images, whether in postage stamps, television, films, etchings, or iPhone photographs. With this proliferation of images, how do we go about thinking about art? It is much harder to apply a definitive hierarchy. So how does one learn? Where do you begin?

Perhaps the best approach is to focus on a single image, whatever its origins, ignore the thousands of others, and ask yourself: where did this image come from? How is it made? How is it disseminated? For what does it stand? How can it be used? Then one has to question how capable the artist was in achieving his or her aims. Please remember that Don Marron did not collect conceptual, video, or installation art, and almost never any sculpture. His passion was for paintings and works on paper, so I was happily circumscribed by his self-imposed restrictions.

ADBefore you worked for Mr. Marron, you worked at MoMA in New York and also at the auction house Christie's. I understand you met him while you were working at MoMA?

MAI was at a Sotheby's preview one weekend; I was a graduate student in a dirty sweater and looking at a 1926 Miró. I got chatting about it with an exceptionally tall, rather shy man, who was a good bit older than myself. Some months later, I was at the MoMA Christmas party and they introduced the museum's new president who got up to speak; it was the exceptionally tall, somewhat shy man I had spoken with at Sotheby's. Years later he did indeed get a fine 1926 Miró.

The best collections are built through a genuine passion for art and are the fruit of enthusiasm, rather than the vigilant bean-counting mindset of a cost accountant.

Don was a nice guy. A decent man; very equanimous. He found everybody's opinion interesting and worthwhile; he wanted to know what people thought of art and he would often ask gallery assistants, people at the office, his driver—non-art people. He knew that specialists—dealers too—set out certain points of view, which he respected for the most part, but he also valued the unfettered opinion of an interested but comparatively uninformed party, whatever their background.

He was reserved but friendly and, most of all, enthusiastic. He was a powerful Wall Street guy, but when it came to art, he was almost boyish. He loved creative people—he loved a creative turn of phrase; a novel approach. He enjoyed his colleagues who could find creative solutions, and he was greatly inspired by visual constructions—paintings, drawings, prints. He was interested in people who could see just a little beyond the frame, whose art seemed to open the door a little bit wider, or compelled you to think more dramatically.

ADYou worked with Mr. Marron for over 20 years. How did you go from bumping into him at auction previews to being curator of the corporate collections and his personal art advisor?

MACorporate collection! Don hated that! He was always quick to say the PaineWebber Art Collection was not a corporate collection. A corporate collection is staid, predictable, acceptable, and never very interesting—the art you see in lobbies and airports. Don wanted to present a personal collection that was owned by a corporation, and that is how he had begun the PaineWebber Art Collection, which represented the taste forged initially between Don, Susan Brundage, who worked for Leo Castelli, and Monique Beudert, who was a friend and colleague of mine from MoMA.

I'd been teaching at university and working at college museums when the job of curator of the PaineWebber Art Collection came up in 1995. It was funny. I went into his intimidating office, and in came the tall, modest man. 'Oh, I remember you', he said. It was the friendliest job interview known to man. I got the job.

ADMr. Marron, as you say, was a Wall Street man, whereas you came from the art world. How would you describe your working relationship?

MAWe were able to tune in to each other's differences to see the similarities we shared in art, and we worked together in great measure because of our differences. There were extremes. If he was working fast, I'd slow down; if I was racing about, he'd slow down. We drove each other crazy sometimes. When he was in a furious hurry, I'd have to distil everything I knew about a work or an artist in a breathless frenzy, summoning up all my verbal skills to convince him to commit a quarter of a million dollars, sometimes to something he hadn't even seen. He joked that his job was to try and talk me out of a piece of art, and my job was to do the same for him. After a debate, if we both agreed, it was a done deal.

He was interested in people who could see just a little beyond the frame, whose art seemed to open the door a little bit wider, or compelled you to think more dramatically.

We'd go to the Brooklyn Museum for the Sigmar Polke show, for example, knowing that Michael Werner Gallery would present Polke's work the following season. We whirled around Los Angeles a few years ago, going from a visit to Ed Ruscha, to Mark Grotjahn, and on to Mark Bradford. Sometimes Don would tear out a page from Artforum, pointing to a photograph of, say, a work by Andreas Gursky, and say, 'We have to call this dealer right now and find out if we can get this. I cannot believe you haven't shown this to me yet.' Sometimes I would call him at the very last minute in Paris describing the crossfire at an auction. There was no set way of working together, because we were flexible and knew we had to be in a world that was constantly in flux. We trusted each other to keep the other's perspective in mind.

ADYou worked as a curator of the PaineWebber Art Collection, which became part of the UBS Art Collection, then as the Lightyear Capital art collection's curator, but you were also Mr. Marron's personal art advisor. How did you work out what he liked, with regard to these different roles?

MADon mainly collected modern and Impressionist works for his home, focusing on contemporary art for the workplace. I worked out early on that he wasn't so keen on sculpture, strident political art, or nudes. He was drawn to abstract work. In some respects, he followed my taste, while in others, he set the tone. There are a few works that I actually had to beg him to buy, and about which he was quite resistant. On occasion, he was right; but just as often, he learned to love the works he had initially disparaged.

Perhaps the best approach is to focus on a single image, whatever its origins, ignore the thousands of others, and ask yourself: where did this image come from? How is it made?

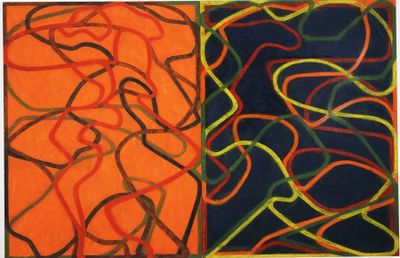

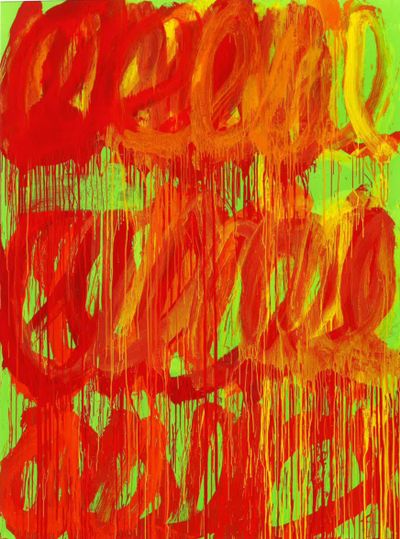

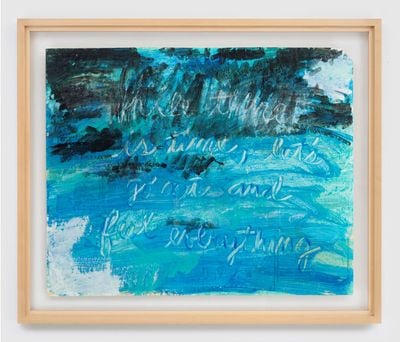

The gallery space at the Fuller Building very much reflects the sensibility of Don's personal collection. Walking into the room, you are immediately struck by the vivid colours, and the physicality of the constructions—whether the ribbons of high-intensity colour in the work of de Kooning or Twombly, Marden, or Bradford. There is a robustness and large scale to the work, and an immediacy of sensibility. The work hits you chromatically before you can take it in—like a burst of fugue rather than a description or explication of a musical phrase.

I remember asking Don early on what it was, exactly, he wanted me to find. And he said, 'Your job is to find me the best art.' He was way too smart to have a shopping list or to restrict with guidelines. He trusted my taste and understanding of his, and he was happy with the result. For the most part.

ADWhile you speak of being tasked to find the 'best art', the picture you are also painting is of a collection built in a far more playful and passionate way than one might expect. I imagined a much more structured approach.

MACollecting should be fun, and being an art advisor means you encourage the passion of your client without forgetting the financial aspect. Early on, I found him a great painting by Paul Klee. He asked me if it was at a fair price. I gave him the dollar amount then added, 'I'm looking at it primarily from an art point of view; I can make an argument for the money either way.' A quizzical, dismissive glare. I added, 'Well, I mean, it's not my money.' Another furrowed grimace, and he intoned: 'Always act as if it is.'

The idea is to show Don's sensibility as it developed, enlarged, contracted, and expanded—to show how he reached back, how he looked forward, what he collected recently, what he collected years ago, and how he was frequently ahead of the curve.

The best collections are built through a genuine passion for art and are the fruit of enthusiasm, rather than the vigilant bean-counting mindset of a cost accountant. Don never said, 'We need to find more German Expressionist etchings', or, 'We need a Colour Field painting'—never, never, never. I found him great paintings that he wouldn't have considered had I told him first about the type or school from which it had come. He was not crazy for minimalist paintings, yet he was wildly enthusiastic about a particular work I'd found by Agnes Martin, and another by Bob Ryman. He would've said he didn't care for conceptual work, yet he had a fine Barry Le Va. He preferred abstraction to figurative work, but was highly enthused by Jonas Wood, Alex Katz, and Chuck Close. Don preferred gestural paintings, but he acquired a dream of a painting directly from Ellsworth Kelly—a stately rectangle of green over blue.

A collection should be an expression of one's self. I think of a collector as akin to a jazz musician or a filmmaker: they're creative in the combination of fragments they've considered, evaluated, and fused together, and they make mistakes because they've taken chances. Don took time to find the work that he truly felt was right for his own tastes. As much as some art collectors—or as I call them, 'art buyers'—believe otherwise, a worthwhile collection takes time to make. It can't be done at a single auction or art fair. Keeping that in mind, I gotta say there's nothing like the thrill of discovery. Good discoveries make one feel like Galileo. I imagine.

ADGagosian, Pace Gallery, and Acquavella Galleries have proposed a joint exhibition honouring Mr. Marron as a collector. How do you see an exhibition as achieving this?

MAThe idea is to show Don's sensibility as it developed, enlarged, contracted, and expanded—to show how he reached back, how he looked forward, what he collected recently, what he collected years ago, and how he was frequently ahead of the curve. I'm also keen to see how what he collected in the 1970s informed what he bought years later. For example, Don was very fond of work by Richard Diebenkorn. Remember, he started collecting in the 1960s before the 'art world' became 'the art market', and much of the same sensibility he was attracted to in Diebenkorn's paintings carried through, like a particular chord of music, from one artwork to another years later. Collecting is not a static sensibility; it develops and shifts, and this is what made Don interesting as a person and collector. He had a clear sense of what he liked and was willing to see it mutate.

I think of a collector as akin to a jazz musician or a filmmaker: they're creative in the combination of fragments they've considered, evaluated, and fused together, and they make mistakes because they've taken chances.

Arne, Bill, and Larry were all, in different ways, friends of Don's. They really do want to honour the idea of a passionate collector, because a lot of what we have nowadays is passionate buyers. His idea of being a collector was distinct from so much of what we see today. An analogy would be the differences between, say, a developer as opposed to an architect: Donald Trump to Frank Lloyd Wright.

ADYou speak in an almost nostalgic way about how Mr. Marron collected.

MAAh, well. Maybe it's because he was the last of the old timers. He lamented that the 'art world' had become 'the art market'. The idea of collecting in order to realise a profit was something he found antithetical to the idea of art. What he loved was to imbibe the energy of creative thinking. It was this, more than anything, that made him a good collector and, I suspect, a good businessman: he sought out creative impulses. He loved talking to artists, developing new points of view. He believed in Modernism—that expressions of intelligence or great feeling were inherently good for everyone. I know that he saw art as a respite from labour and the mechanics of the world economy. This notion of seeing it as 'great investment potential'—of seeing art in terms of its alchemical potential to turn into money, which he saw as vulgar—was beside the point. It was missing out on what was important.

ADWas there a favourite work in the collection for both of you?

MAYes. A late great pastoral and celebratory painting by Twombly from 2007. It's an immense work—about 20-feet wide and no less than 9-feet high—that is as suffused with lyrical passages and poetry as anything Twombly ever made: washes of apple green and brilliant white, along with a floral motif interlaced with the lines from a haiku. It is an overwhelming mural, but it still manages to be intimate, fragile.

I unpacked it myself and looked at it alone. There it was: a glowing triumph, a tempest of flame and energy, his valediction.

ADWhat else can you share about working with Mr. Marron?

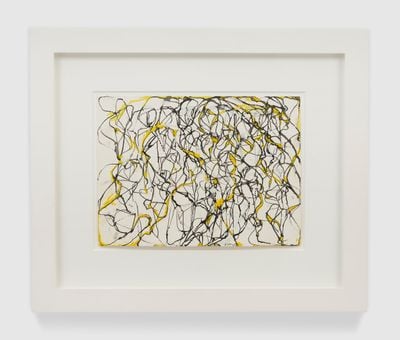

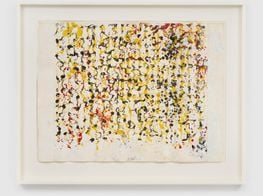

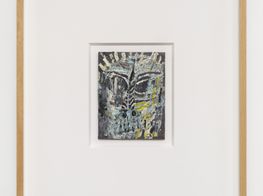

MAOh, he just loved the thrill of acquiring work that was vivifying and strong. Last November, Brice Marden had a show at Gagosian in New York. The paintings upstairs were large, intense interloping calligraphic ribbons with wide monochromatic bands on either side of the canvases; strong paintings that are chromatically intense and mysterious. Downstairs, there were several large works on paper, dominated by a quartet of vertical ink drawings—high-coloured visions of dark dreams and hopes conveyed through whiplashes of red, blue, and green.

There was one work in particular—rich in glowing, glowering garnet red—that was phenomenal, and I knew Don would want it. I got him on the phone and told him to come immediately. He said, 'I'm in the middle of a meeting'—a phrase that sometimes meant he really was in a meeting, but could also mean, 'come on, convince me!'—so I kicked into linguistic high gear, resulting in him leaving his meeting and coming straight to the gallery, where he bought the painting on the spot. I knew when I was right, he knew when he was right, and we both knew when the work was right.

In the days that followed, another collector—also a MoMA trustee, I was told—urged, insisted, maybe pleaded with Don to relinquish his hold on this work so he could acquire it himself. This only made Don more pleased with his intent to acquire it. Sadly, Don passed away before the deal was finalised but his family and business associates, who knew of his passion and had heard the triumph in his voice when he talked about it made sure it became part of the collection. It came to the gallery shortly after Don died. I unpacked it myself and looked at it alone. There it was: a glowing triumph, a tempest of flame and energy, his valediction.—[O]