Neil Printz

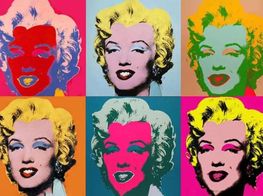

As part of a collaboration between The Andy Warhol Foundation of the Visual Arts and Phaidon Press, the first volume of The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné

was published in 2002. Initiated in 1976 by dealer Thomas Ammann, the aim of the catalogue is to provide a comprehensive record of Warhol’s entire body of work, which is estimated at some 18, 000 pieces—paintings, sculptures, and drawings—produced between the late 1940s until Warhol’s death in 1987. Now, some 12 years since that initial publication, Volume 4: Paintings and Sculpture Late 1974-1976, has been released, featuring over 600 artworks (including previously undiscovered and lost works) created in a period of less than three years: the first in a series of volumes that aims to capture what has been described as ‘a remarkably productive ten-year period for Warhol during which he worked in his studio at 860 Broadway in Manhattan.’

In this interview, Ocula discusses the latest volume with Neil Printz, co-editor of Volume 4 along with Sally King-Nero. Formerly Editor of the Isamu Noguchi Catalogue Raisonné and Research Curator for Twentieth Century Art at The Menil Collection, Houston, Printz also co-edited the first two volumes of the Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné. Paintings and Sculptures, 1961–1963 and Paintings and Sculptures, 1964–1969 and was editor of Volume 3: Paintings and Sculptures, 1970–1974.

The Andy Warhol Catalogue Raisonné, Volume 4: Paintings and Sculpture Late 1974-1976 is the first in a series of books to document what you describe as a remarkably productive ten-year period for Warhol. What have you discovered about this period in light of the 600 works you compiled for this volume? In other words, what does this volume reflect about Warhol as an artist in relation to other periods within his career?

Volume 4 opens as Warhol changes studio, moving across Union Square to his new studio at 860 Broadway, where he would work for the next ten years. Even as the move was taking place around him, Warhol continued to work, photographing the transvestite models for his new series of paintings, drawings and prints—Ladies and Gentlemen, and producing the earliest paintings in the series. I’m always struck by the fact that Warhol worked constantly and how he improvised his workspaces. In Volume 4, we see him setting up different kinds of places to work within the 12,500 square-foot domain of 860 Broadway: for example, in interstitial places like a small, unremarkable wall in the reception area where he posed his portrait sitters, or in spaces set out for other uses like the screening room and storage areas at the back of the studio, both without natural light, that he appropriated as painting studios. At 860 Broadway, Warhol’s varied and interlocking enterprises—painting, drawing, photography, video, archiving, writing and publishing—finally become consolidated into a single space, but he had to carve out places of his own to make his paintings.

What was the process of producing this volume, logistically speaking? Who did you work with and how wide a field did you have to go to bring this content together?

Assembling a catalogue raisonné is like detective work. It is based on the evidentiary procedures of art history: the testimony of eyewitnesses (the artist’s assistants, colleagues, and friends), tracking the paper tail (the documentary and archival record), above all, carefully examining the body (the material record of the work of art itself), and its companions (the corpus). I always begin with an outline that gradually takes shape as our research proceeds. I try to find the narrative of Warhol’s studio—in New York and on the road. I like to think that one volume leads to the next, but that each volume has distinct contours—a story of its own. Each volume takes several years to complete. The Catalogue Raisonné team consists of six people including me, but it involves the participation and collaboration of literally dozens of people.

Could you talk about the Ladies and Gentlemen series: 268 portraits of drag queens commissioned by dealer Luciano Anselmino and the some 500 Polaroids also presented in the volume's appendix? You have described these as Warhol's most extensive, complex, and theatrical portrait sittings?

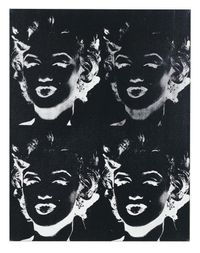

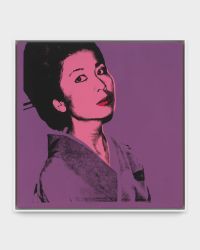

Warhol photographed fourteen transvestite models for the Ladies and Gentlemen series, which consisted of paintings, drawings and prints. Warhol’s models were not Factory superstars like Candy Darling (who had died on March 21, 1974, several months before he began the series), Jackie Curtis or Holly Woodlawn, or show queens, but drag queens who lived urgent and precarious lives on the street. Slightly more than 100 paintings were commissioned and exhibited in the 15th century Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, Italy in late 1975. Most of the exhibition was acquired by one collector, who warehoused the paintings in Switzerland. They were rarely seen except for a one-day exhibition that he organized during the 1988 Venice Biennale, one year after Warhol died. It was staged rather theatrically in a former Benedictine abbey across the Grand Canal from the Piazza San Marco. Warhol painting more than two and half times as many paintings than were required by the commission. Most of these paintings never left his studio, where they remained, mostly stretched but unseen, until after his death. Years after the series was completed, Warhol remarked to an interviewer that he “may have been thinking of Picasso at the time.” Indeed! I think the Ladies and Gentlemen series resonate with the virtuosity and invention of Picasso’s late work. Volume 4 reassembles this virtually unknown but brilliant series for the first time, as well as the complete portrait sittings of all fourteen models—slightly over 500 Polaroids in all.

Fascinating! And to your mind, how does the Ladies and Gentlemen series resonate with the virtuosity and invention of Picasso’s late work?

I’m thinking of the way that Warhol in the Ladies and Gentlemen paintings, like Picasso in his late work, pushes his visual language to its limits. For Picasso, the language was Cubism, for Warhol the dissonance between painted and printed surfaces. Their expressive motivations may have been different—Warhol was in the middle of his career, Picasso at the end. Picasso died in 1973, about a year before Warhol embarked on the Ladies and Gentlemen series. Not to put too fine a point upon the parallel, but Warhol’s Ladies and Gentlemen paintings, like Picasso’s late works, are visually explosive, about extremes.

The volume also includes portraits of cats and dogs and the American Indian series—could you talk about how these works sit in relation to Warhol's oeuvre? In other words, how do these works expand on our knowledge of Warhol as one of the seminal artists of the 20th Century?

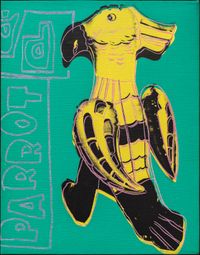

Both series highlight Warhol’s painterly accomplishments and his feeling and daring use of color, although his subjects are entirely different: intimate but utterly unsentimental portraits of people’s pets, including his own dachshunds, on the one hand, and imposing, monumental portraits of the American Indian activist Russell Means, on the other.

That his subjects are entirely different—how does this add to these particular series, given the volume pays particular attention to them? Further to this, as a volume, what side to Warhol—in terms of how he approached his subjects—does this reveal?

I like to think that the Catalogue Raisonné gives each new series due consideration, and that we examine the multiple determinations that moved Warhol, as well as the way each body of work developed. Warhol loved animals and the Cats and Dogs portraits are tender and elegiac; nonetheless the series evolved from a still life project that began with paintings of mounted animals purchased from taxidermy and antique shops and developed into a portrait series. In a sense, their exhibition in London touches on a cultural cliché—the fondness of the English for their pets. This is somewhat similar to the exhibitions of the American Indian paintings, which took place in Los Angeles and Vancouver—out West. Warhol was fascinated by Hollywood, but he was also a passionate collector of Indian art from the Pacific Northwest coast and the American Southwest. Typically we think of Warhol as an open book, but lesser known series like these reveal how layered his choices could be, how contradictory, and complex.

This volume is the latest product in what was initiated in 1976 by Thomas Ammann. How does it feel to be part of such a large undertaking?

To study a single artist in detail over many years is a dispensation. I feel especially lucky to have been granted this kind of intense and privileged access to the work and world of an artist who changed the face of art in our time—Andy Warhol.

What are the challenges in producing such a complete and extensive record of Warhol's work?

Warhol was famously productive; his work remarkably inventive. There is always more to see and learn. When Warhol died he left behind an unprecedented if unsystematic record of his art in hundreds of boxes of ephemera, including approximately 600 Time Capsules. Likewise, the Warhol market is exceptionally active and Warhol studies represent a veritable industry of new exhibitions and publications. All of this keeps us on our toes!

In working on this project, how have your views on Warhol changed or evolved?

As long as I can remember, I have been passionate about Warhol’s work. Working on the Catalogue Raisonné for the last twenty years, I have found that my perspective on Warhol has changed, rather than my views or opinions.

In that case, how has your perspective changed having worked so closely with Warhol's body of work?

My focus is always on Warhol’s paintings, sculptures, and drawings, but more and more I find myself factoring in the role of Warhol’s other activities and the wider field of his enterprises, for example, filmmaking and photography, writing and publishing. I am fascinated as well by the dynamic between his commissioned portraits and works in series. I am also more attentive to the reception of each new body of work during Warhol’s lifetime. By definition a catalogue raisonné is work-centred and material-based. As we proceed, however, volume by volume, I have found myself more open to and interested in a narrative that takes in Warhol’s life and as well as his works.—[O]