Fashioning a South Asian drift: the 9th India Art Fair

Dhruvi Acharya, Ashes (2015). Installation view: Chemould Prescott Road, India Art Fair, New Delhi (2-5 February 2017). Courtesy India Art Fair. Photo: Manoj Kesherwani.

The India Art Fair also served as a platform to launch new ideas and announce forthcoming plans for both artists and galleries.

Now in its ninth edition and its first year under the wing of co-owning art fair powerhouse MCH Group, the New Delhi-based India Art Fair opened on 2 February (running to 5 February) with a more focused South Asian directive. Moving on from its early days, when the fair appeared to position itself as an international event complete with invited gallery bigwigs, India Art Fair—billed as 'the largest contemporary art event in South Asia'—is on its way to finding its niche as a 'portal to the region's cultural landscape'.

Gone are the spectacular installations and the art-world gimmickry that shadowed so many of the fair's former editions, allowing for a better structured and more meaningful focus on representing Indian art within a South Asian dimension.

Fifty-three gallery booths from across India (including Art Pilgrim and Shrine Empire Gallery) took part this year, in addition to a dozen from overseas (including Kalfayan Gallery and Aicon Gallery). Also invited were artist collectives from Bangladesh (Britto Arts Trust), Nepal (Nepal Art Council) and Sri Lanka (Theertha International Artists Collective), six India-based institutions (from the Korean Cultural Centre India to Swaraj Art Archive), and sixteen artist projects (including those by Mithu Sen and Anila Quayyum Agha).

Purposeful and reflective of the developing trends in a rather slow market, many galleries chose to exhibit artists' work that were shown in the past year. Though this could be seen as repetitive, these presentations offered an insight into the programming of art spaces across the region.

The fair's layout positioned bigger galleries together at the front of the NSIC Exhibition Centre, in keeping with previous years. Kolkata's Experimenter displayed works by a number of artists including Dhaka-based Ayesha Sultana, whose current show at the gallery is titled Making Visible (21 January-27 February 2017). The recipient of the 2014 Samdani Art Award, Sultana's five 2016 graphite on paper drawings Untitled, Untitled (Fragments) I, Shift III, Shift IV and Shard (2016-2017) are spatial investigations based on the architecture of Dhaka.

Other works on view in Experimenter's booth pointed to a general focus on architectural or urban themes. In XXIII.XII.016-XII.01.017 (2016-17), French artist Julien Segard's exploration of the urban underbelly is layered into a suite of nine collages. Similarly, Indian artist Rathin Barman explores the urban landscape by fleshing out paradoxes in built environments—Barman's skeletal piece Moulding of Homes (Site II) (2016), for instance, is made of brass inlaid in concrete, and was inspired by the journeying of migrant workers and the notion of home.

Likewise, Mumbai gallery Chemould Prescott Road delved into India's social landscape, with works by artists including Dhruvi Archarya and N. S. Harsha, who recently opened a major survey titled Charming Journey (4 February—11 June 2017) at Tokyo's Mori Art Museum. Harsha's large triptych painting presented in the booth, Untitled (2016), is a critical social graph of Indian men and women seated on plastic chairs, often found in various social spaces, from tea shops to temples.

New Delhi-based Photoink offered another stand-out presentation, with black and white photographs by the likes of Prabuddha Dasgupta, Dileep Prakash, Ketaki Sheth, Sooni Taraporevala, and Pablo Bartholomew, each presented as a suite. Particularly gripping are the pigment prints by Roger Ballen from the series The Theatre of Apparitions (2009—2012): black and white images that focus in on architectural interiors in order to frame ghostly figures that the artist painted in.

Exemplary of what the artist calls a 'documentary fiction' approach to photography, the series originates from an image Ballen took in 2004 of a blacked-out window at an abandoned women's prison, and is designed to dramatically lead viewers into the internal structures of the subconscious. On an adjacent wall were abstract camera-less photographs of young Chennai-born artist Srinath Iswaran, executed with handmade paper stencils and the dispersion of light.

Among the returning galleries from abroad were Madrid's Sabrina Amrani Gallery, presenting minimal conceptual works by Joël Andrianomearisoa, Ayesha Jatoi, Timothy Hyunsoo Lee and UBIK. Dubai's Grey Noise showed UAE-based Lantian Xie alongside three artists of Pakistani origin—Fahd Burki, whose graphic practice is informed by geometric abstraction, Mariam Suhail, whose work subverts common objects and text, and Lala Rukh, a feminist artist-activist whose debut solo at Grey Noise is scheduled from 13 March to 13 May 2017.

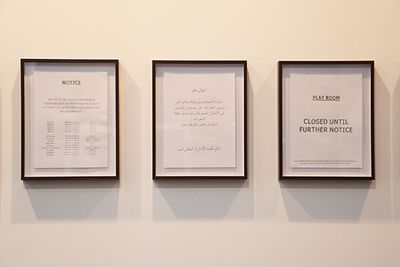

Xie's work has been part of two recent Asian biennales in the past year: the 11th Shanghai Bienniale curated by Raqs Media Collective, and the 3rd Kochi-Muziris Biennale, curated by Sudarshan Shetty. Reflecting on the artist's use of drawing as a form of potent intervention, Xie showed a series of eight pencil on paper works titled Notice (2017), through which the artist investigates states of belonging and displacement by drawing several notices written in English and Arabic found posted in apartment buildings.

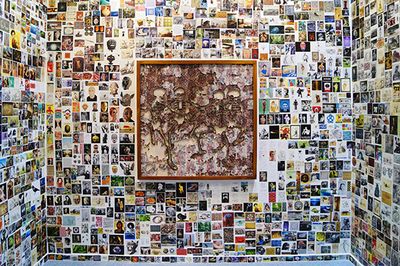

Of the artist projects' that resonated with the contemporary moment were Avinash Veeraraghavan's Dwell in Possibility (2017), supported by GALLERYSKE, and Reena Saini Kallat's Woven Chronicle (2011-16), supported by the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA). Veeraraghavan's project consists of three laser-cut panels and a video presented in a room covered with thousands of images—ranging from sketches, to photographs and stickers—from the artist's archive.

The installation's title draws on an Emily Dickinson poem of the same title, which alludes to a welcoming space with limitless possibilities and multiple interpretations. This titular frame was reflected in the physically layered panels—both a reflection of the world's vast and complex humanity, and a comment on the collective consciousness manifested through the circulation of images and information in the digital age.

Meanwhile, Kallat's piece re-imagines the world with electric wiring and circuits that form a woven map, with wires acting as conduits and barriers, simultaneously referring to global networks of communication and commerce as well as to barbed wires and fences.

Sounds of the deep sea, factory sirens, and bird calls are also audible—an attempt to awaken the viewer to the convoluted routing of contract workers, refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants routinely traveling across borders. (With the impact of the sound a tad lost in the bustling fair, the work nevertheless did well to add another ironic layer of 'noise' to the fair floor.)

Reflecting on India Art Fair's re-branding as South Asia's modern and contemporary art fair, the Delhi Art Gallery presented a curated section titled Masterpieces of Indian Modern Art, Edition II, which featured iconic work of the likes of Chittaprasad (1915-1978), J. Sultan Ali (1920-1990), Manjit Bawa (1941-2008) and Somnath Hore (1921-2006) alongside text, film, informative touchscreens and well-researched publications.

The effort to put together a section of the fair that stood apart from the booth format was commendable, and the focused editing and quality of art was especially impressive. (A welcome relief from past editions, when the gallery gloried in overwhelmingly large historical presentations of Indian art from the Company School Paintings of the colonial era, to Kalighat Pat and the Bengal School, and the Period of Indian Modernists.)

The India Art Fair also served as a platform to announce forthcoming plans for both artists and galleries. Vadehra Art Gallery divulged new partnerships with artists N. S. Harsha, Jagannath Panda and Riyas Komu by presenting their works in their booth, while PhotoInk's display of erotic floral prints by Prabuddha Dasgupta foretold the collaboration with the late photographer's estate.

Meanwhile, Gallery Espace introduced Aadi, a branch of the Delhi-based gallery devoted to the promotion of Indian folk and tribal art. Aadi presented a solo project booth featuring an exquisite range of antique leather puppets from Andhra Pradesh shown alongside A Tale of Two Cities, a collaborative residency project by 11 artists working between Varanasi, India and Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. The project was organised by Gallery Espace, Serendipity Arts Trust and Theertha International Artists Collective, and was recently presented at the Serendipity Festival in Goa, India between 16 and 23 December 2016.

These new developments also pointed to a tentative revival of craft and tribal art, as signalled in the Fair-supported exhibition project Vernacular In Flux, which was somewhat awkwardly positioned as an exhibitor booth. Curated by art historian Annapurna Garimella and executed in collaboration with Devi Art Foundation, Mithila Art Institute and Ojas Art Gallery, the project brought together the Indian folk art of Madhubani, Maithili and Gond, with works by nationally awarded and internationally recognised artists such as Bhajju Shyam, Vimla Dutta and Baua Devi.

Similarly, Exhibit 320 featured artists who employ craft as a method of working. Sumakshi Singh embroiders floating floriated patterns as a way to archive fleeting memories, and Vibha Galhotra engages community women to help produce large-scale conceptual works from ghunghroos (tiny bells used in anklets, often by dancers).

This emerging focus, together with the modern and contemporary artworks on view within the fair illuminated the ways artists from the region are crafting their views on contemporary times by reinventing the creative process in a manner that speaks to and of the Indian landscape and its place within the larger geopolitical structures of South Asia and the global economy.

This intersectional rhythm also resounded beyond the fair's venue into a series of collateral projects. Devi Art Foundation and Gati Dance Forum attempted to negotiate the vocabulary of performance through three specific collaborations between contemporary dance practitioners and visual artists. As an ongoing exploration into the relations between contemporary art and dance, the programme #INTERSECT was first performed at the 4th edition of New Delhi's IGNITE! Festival of Contemporary Dance in October 2016, and was presented again during the fair for those who missed the first iteration.

One of the three performances, The Big Dream, inspired by David Lynch's music album of the same name, is plotted around the meeting of two dreamers who explore childhood fantasies and indulgent daytime reveries. Choreographed and performed by Surjit Nongmeikapam, with visual inputs by Kartik Sood, the 35-minute performance combines magical moments with fraught thoughts to produce a visual projection of fantastical minds.

Offering another reflection of Indian art within a global context is the Gujral Foundation exhibition The Open Hand at arts venue 24 Jor Bagh, which opened on the same day as India Art Fair and runs to 5 March 2017. The show includes four commissioned projects conceived for international platforms.

These included Vishal K Dar's light installation Antraal (2017), based on a work produced for the 11th Shanghai Biennale; the Contour Biennale 8-commissioned film by Basir Mahmood and Pallavi Paul, In a Move, to the Better Side(2012), which is based on a 2011 incident involving a group of 21 illegal immigrants from Pakistan who suffocated to death en-route to Europe in the container they were being smuggled in; works created by Shilpa Gupta for the 56th Venice Biennale, which represent four years of ongoing research into the India-Bangladesh borderlands and one of the world's longest security barriers between two nation-states; and Desire Machine Collective's film Invocation (2016), which was produced for the British Museum exhibition Krishna in the Garden of Assam (21 January-15 August 2016).

Over the last two years, the landscape of art in the Indian subcontinent has come to represent an acute pulse of the region through a series of keen collaborations, and well-researched exhibitions. The regional focus of the 2017 India Art Fair and the parallel programming by both institutions and private galleries around the fair reflects a desired maturity among the various agencies that position and promote art.

In a world where globalisation and digitisation are the contemporary norm, artworks and exhibitions on view within and around the 9th India Art Fair seemed to look inward, seeking a deeper engagement with the region's lands and cultures in order to develop a truly South Asian drift. —[O]