Lubaina Himid Puts the ‘Her’ in ‘History’

Lubaina Himid, Le Rodeur: The Pulley (2017). Acrylic on canvas. 183 x 244 cm. © Lubaina Himid. UK Government Art Collection. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens, London. Photo: Gavin Renshaw.

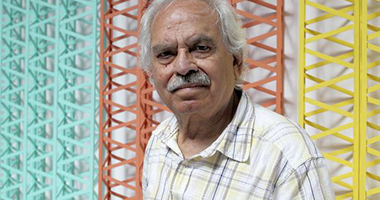

In an essay published in Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain (2005), Rasheed Araeen—a leading voice in the British Black arts movement and founder of Third Text—credits Lubaina Himid with creating spaces for Black women 'without the interference of men'.

Araeen cites the 1985 show The Thin Black Line in particular, which Himid organised at the ICA in London with 11 artists of African, Caribbean, and Asian descent, among them Sutapa Biswas, Ingrid Pollard, and Chila Kumari Singh Burman, recent winner of the Tate Britain 2020 Winter Commission.

Himid was a central figure in the British Black arts movement, aligning with the conception of political Blackness that reflected the politics of the time. Diaspora and migrant communities in the country stood against structural and social racism just as non-aligned connections across Africa and Asia opposed what Kwame Nkrumah called the West's neo-colonialism.

The Thin Black Line was one of three shows Himid curated in the early 1980s, alongside Five Black Women at the Africa Centre in 1983, and Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre (1983–1984). Each confronted what Himid described as a double negation, of being Black and a woman.

Trained in theatre design at the Wimbledon College of Art, Himid calls herself a political strategist: an apt description of a multidisciplinary artistic practice embracing curation, activism, and teaching (she is a professor of contemporary art at the University of Central Lancashire).

In keeping, Himid's work is infused with a Brechtian theatricality, with cut-out figures in particular activating galleries as social spaces and platforms of political engagement.

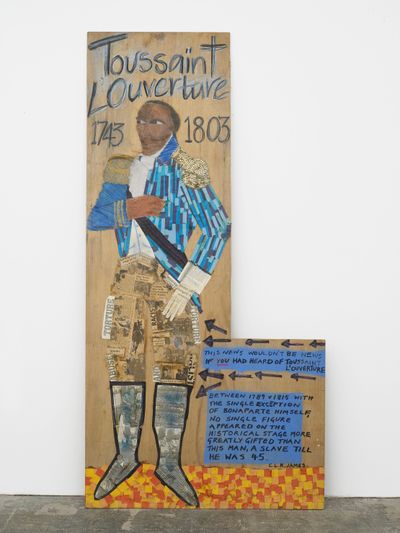

Le Toussaint L'Ouverture (1987) is a cut-out portraying the leader of the Haitian Revolution, known as the only successful slave revolt in history that led to the establishment of independent republic of Haiti in 1804.

Himid's figure is covered in collage. One half of his military jacket is beautifully constructed from rich blue strips, while his trousers and boots are covered in newspaper clippings. Isolated words like 'Abuse', 'Torture', and 'Racist' frame reports with headlines that read, 'Nursing home says no to brown people' and 'racist childminder still at work'.

By L'Ouverture's legs is a quote by Trinidadian activist and journalist CLR James, who equates the former slave's historical greatness as equal to his arch enemy Napoleon Bonaparte.

'Showing [the work] now,' Himid said in a recent conversation with Marlene Smith, 'will bring up both how much has changed since then and how much is the same'. 1

Ditto The Carrot Piece (1985), a cut-out of a white man on a unicycle dangling a carrot in front of a Black woman carrying a filled basket. This was Himid's response to cultural institutions eager to show they were 'integrating black people into their programmes.'2

An aversion to London's art scene is on full display in A Fashionable Marriage (1986), which was shown as part of the Turner Prize display in 2017, the year Himid, at age 63, became the first Black woman and oldest artist to be awarded the accolade.

Ten figures made of different types of wood reflect the 'greedy, self-serving, go-getting opportunistic mayhem' of 1980s London. 'Everyone who shook or moved in artistic semicircles or political whirlpools was a deserving dartboard', she notes.3

Based on Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode (c.1733–1735), the scene revolves around a Countess—here, Margaret Thatcher—holding a very white court. Six of the figures are covered in collaged elements—whether Art Monthly covers, or with Thatcher, newspaper headlines reading: 'staunch supporter of apartheid'.

On the walls are paintings referencing Picasso, a portrait of Gertrude Stein, for instance. On the floor, a basket of books at the feet of a young girl sitting on a suitcase, evocative of a Windrush arrival, includes The Groundings With My Brother (1969) by Guyanese activist Walter Rodney, a book about Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey's philosophy, and The African Origin of Civilization (1974) by Cheikh Anta Diop.

In the following years, Himid created the 'Revenge: A Masque in Five Tableaux' series (1991–1992), among which Between the Two My Heart is Balanced (1991) removes the Highland soldier in James Tissot's Portsmouth Dockyard (c. 1877), and replaces the two women on either side of him with figures based on Himid and artist Maud Sulter.

Himid describes the paintings as an attempt at writing herself and other Black artists 'into the history of British painting'4—an erasure that she approaches from a feminist angle.

Himid's work is infused with a Brechtian theatricality, with cut-out figures in particular turning galleries into platforms of unflinching political engagement.

Freedom and Change (1984) turns the neoclassical bathers in Picasso's Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race) (1922) into monumental Black women painted on a hanging pink sheet, one holding a leash connecting to four dog cut-outs beyond the fabric. Behind them, two white heads look on from the floor.

In a 2016 conversation for Afterall's 'Exhibition Histories', curator Paul Goodwin, whom Himid worked with on Thin Black Line(s) at Tate Modern in 2012, describes the 1980s as a critical decade with contemporary resonance when it comes to Black arts in Britain. Yet Himid pointed out a gap 'when nobody wanted to talk about this work or these artists'.5

In recent years, however, there has been a resurgence, with solo exhibitions of artists associated with a movement that, as Himid told Sutapa Biswas in 1985, had no unifying aesthetic.

From Rita Keegan at South London Gallery and Claudette Johnson at Modern Art Oxford in 2019 to Sonia Boyce at ICA London, and the Nottingham Contemporary survey of Black British artists of the 1980s, among them John Akomfrah and Zarina Bhimji in 2017.

Then there was the three-year Black Artists & Modernism (BAM) research project launched in 2015 by artist Sonia Boyce, looking at British artists of African and Asian descent, which produced an exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery in 2018 and 2019.

Curated by BAM Senior Research Fellow Hammad Nasar with MAC Curator Kate Jesson, Speech Acts: Reflection-Imagination-Repetition presented works from four U.K. public collections. Himid's painting The Tailor (2010) appeared next to the first work acquired by MAC, James Northcote's 1826 portrait of the Black American Shakespearean actor Ira Aldridge as Othello.

At Himid's solo exhibition at Tate Modern (24 November 2021–3 July 2022), one tailor becomes six in Six Tailors (2019): a large canvas depicting men sat around a table laden with the tools of their trade, in front of a horizontal window framing a moody grey horizon.

The painting forms a diptych with a smaller, square canvas showing a brightly coloured strip of checked tweed crossing diagonally over a bright azure plane, Close Up – Materials for Change (2019).

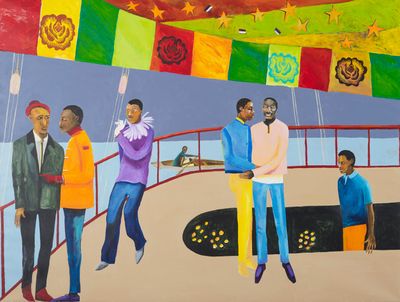

Himid's Tate show is the latest institutional showcase following the artist's 2017 Turner Prize win; it includes the largest showing—four paintings in total—of the 'Le Rodeur' (2016–2017) series.

Referencing a diseased French slave ship that drowned a group of its human cargo to claim insurance, these figurative geometries, with their elegant composure of colour and form, harbour heavy histories.

'I wanted to create something that conveyed a sense of absolute inability to understand what was happening', Himid has explained.6 'The experience should be similar to entering a room and deciding what you're going to do, how you will react and interact.'7 In Le Rodeur: The Pulley (2017), two Black women dressed in their Sunday best stand in a minimalist room whose walls convey a furious, dark sea.

Grey seas are a constant theme, as are textiles—Himid came to the U.K. from Zanzibar in 1954 with her English mother, a textile designer, just a few months after Himid's birth.

The artist's Tate show highlights these threads, showing how cross-hatching fabrics speak to a rough-edged formalism that doesn't just infuse Himid's paintings, but activates the gallery as a grid of representational activation, at the core of which is the Black experience.

In Old Boat/New Money (2019), 32 long wooden planks painted in a spectrum of blue-grey to mauve, are arranged across a wall to mimic the ebb and flow of ocean waves, whose sound emanates from speakers. A cowrie shell is painted at the bottom of each slat, once used as currency in Africa and Asia.

The installation is about reaching 'the heart of a kind of collective memory,' explained Himid on the occasion of her 2019 solo show at the New Museum in New York; 'to get to the centre of something that's falling apart and fading and coming back into view in the way that memory and history do.'8

These memories and histories are at once broad and intimate, soft and severe; they really do reach for the heart. Such that Himid staged her Tate show with textual inserts, with vinyl letters on the wall asking questions like: 'What are monuments for?', 'What does love sound like?', and 'What happens next?' —[O]

1. 'Lubaina Himid and Marlene Smith: young Black artists in 1980s Britain', Art Fund, 23 February 2021,https://www.artfund.org/whats-on/more-to-see-and-do/listicles/lubaina-himid-and-marlene-smith-young-black-artists-in-1980s-britain

2. Lubaina Himid, The Carrot Piece (1985). Artwork caption, Tate, Accessed 7 December 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/himid-the-carrot-piece-t14192

3. Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage (1986). Artist's website, Accessed 7 December 2021, https://lubainahimid.uk/portfolio/a-fashionable-marriage/

4. A.J. rice: 'Alan J. Rice Interviews Lubaina Himid', Wasafiri 40 (2003), p.23.

5. Lubaina Himid & Paul Goodwin, 'Exhibition Histories Talks: Lubaina Himid', Afterall, Accessed 7 December 2021, https://afterall.org/article/exhibition-histories-talks-lubaina-himid-video-online

6. Precious Adesina, 'Lubaina Himid: The artist who skewers white privilege', BBC Culture, 23 November 2021, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20211119-lubaina-himid-the-artist-who-skewers-white-privilege

7. Ibid.

8. Antwaun Sargent, 'Lubaina Himid: Labor and the Art of Becoming', The New York Review, 27 December 2019, https://www.nybooks.com/daily/2019/12/27/lubaina-himid-labor-and-the-art-of-becoming/