Khairuddin Hori: Boundaries and Provocations

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH GILLMAN BARRACKS

I first came across Khairuddin Hori's name in an interview Ocula Magazine conducted in 2015 with artist Tianzhuo Chen. At the time, Hori was deputy director of artistic programming at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, where he oversaw Chen's solo exhibition (23 June–12 September 2015).

Installation view: Tianzhuo Zhen, Palais de Tokyo (24 June–13 September 2015). Courtesy the artist and Bank Gallery, Shanghai. Co-production K11 Art Foundation (KAF). Photo: André Morin.

In the interview, Chen describes Hori as a curator who enabled the artist to test his own boundaries, saying: '[Khai] totally trusted me on this project. Once we set up the framework in the beginning, he gave me lots of freedom to do whatever I wanted.' It is perhaps this statement that best characterises Hori's curatorial practice, one which is also often described as multidisciplinary and unconventional.

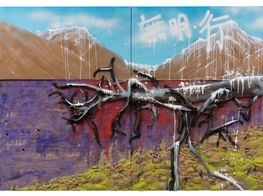

In his current role as curatorial director for Chan + Hori Contemporary in Singapore, Hori appears to be bringing both his vision and his institutional experience to a commercial context, without compromise. In A Totem for Your Genuine Internals (10 January–9 February 2017), Ruben Pang's solo exhibition earlier this year, the artist transformed a space at Raffles Hotel Arcade into a purple neon wonderland. The installation of completely new work was a result of an open invitation to the artist to respond to the space. Likewise the exhibition BOTANIC : ENDEMIC (29 June–23 July 2017) saw parts of Chris Chong Chan Fui's BOTANIC installation—first created for the Singapore Biennale 2013—and ENDEMIC, featuring mechanised plant-like sculptures—originally commissioned for the Secret Archipelago exhibition at Palais de Tokyo (26 March–16 May 2015)—shown together at the gallery's current space at Gillman Barracks. Khai's influence can also be felt in the Singapore art scene more widely. He recently curated LOCK ROUTE (13 January–30 June 2017), an exhibition of outdoor sculptures and installations at Gillman Barracks which was a highlight of the cluster's Art After Dark event held during Singapore Art Week, and which attracted more than 9,000 visitors on its opening night.

You were deputy director of artistic programming at Palais de Tokyo in Paris from 2014–16. What did you learn from that experience that changed how you approach curating?

It blew my mind every day realising that I was collaborating with and surrounded by a pool of talented administrators, project managers, curators and programmers, many of whom came with more than a decade's professional experience at art centres such as the Louvre, Centre Pompidou and Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris. There was a lot of trust between these colleagues; people were respectful of each other's curatorial decisions. This was particularly so with regard to solo projects, which were very open-ended—many without definitive expiry dates—so there needed to be a lot of mutual respect and trust. I learned a great deal from my colleagues through the conversations we had. These are people who have a deep passion for contemporary art and who all ardently follow its international developments.

It was a common understanding among colleagues from various departments that art and artists always come first. Curators worked continually with artists to develop their projects, allowing sufficient time and freedom for proper resolutions to be achieved. Through weekly curatorial meetings, we would update the team on the various projects we were working on, receive feedback, take suggestions where appropriate and coordinate and harmonise with other projects taking place.

As an example, the technical head would sit in on meetings with artists to listen to ideas and technical challenges proposed for a project. They would then return to offer solutions and options for the artists and curators. This allowed artists to dream of projects they would not otherwise have the capacity to execute, especially not by themselves. It was this quality of professionalism and sense of fraternal pride in what we were doing that stood out and has had a lasting impact on me.

While at Palais de Tokyo, you curated a solo exhibition featuring the work of Tianzhuo Chen. This exhibition was theatrical in many ways. I understand you have a background in theatre. Can you tell me about how you view the relationship between theatre and contemporary art in terms of your curatorial approach?

Yes, I do have a background in theatre—and performance art too—but I cannot say that this influenced my invitation to Tianzhuo Chen to show at Palais de Tokyo. I do believe it is in fine arts that elements such as colour, texture, form, composition and time—also foundations of all arts—reside or emanate. I chose to invite Tianzhuo because I feel his practice and artworks run closely alongside contemporary realities such as rap culture, drug use, fashion and religion, yet they feel disconcerting as art. His aesthetic is also one that is very separated from that of most emerging artists from China and elsewhere. For example, the video PARADI$E BITCH (2014) features twin performers rapping over a Cantonese song by CHEE:Kidgod featuring Vyan in a style borrowed from black American hip-hop culture. The twins have been 'tattooed' with drawings based on Tibetan Buddhist iconographies and Tianzhuo's responses to them. At the same time, they don heavy jewellery with contrasting symbols of wealth, drugs and mortal power. In my opinion, this appropriation of religion and rap culture is not intended as an effort to copy or parody, but as raw material that speaks closely to today's youth.

I began my journey in art through participating in traditional Malay cultural activities. At that time, my influences were literature, folk music and the theatre of the Malay Archipelago. In Singapore, I was also exposed to the work of artists from The Artists Village as we encountered each other through exhibitions and hang-outs near The Substation, National Museum Art Gallery and a quaint coffee shop in front of the old National Library on Stamford Road. Through such and other life experiences, I constructed a holistic picture of how artists and art could be engaged with and presented.

The Artists Village is an incredibly important part of Singapore's art history. Can you discuss the artist colony further?

The Artists Village began in the late 1980s. Tang Da Wu—who had returned to Singapore in 1979 after finishing his studies in the UK—opened a relative's farm in rural Lorong Gambas to artists. Artists from the initial period of The Artists Village's history include Baet Yeok Kuan, Lim Poh Teck, Amanda Heng, Vincent Leow, Wong Shih Yaw, Lee Wen, Juliana Yasin and Faizal Fadil. At the village, these artists experimented with art forms such as installation and performance, and were seemingly more interested in process instead of a finished product and ornamentation. The formation and significance of The Artists Village became more apparent when S Chandrasekaran, Goh Ee Choo and Salleh Japar—known collectively as Trimurti—came onto the scene in 1988 with equally challenging art that was seen as opposite to that mentioned previously—and rather embedded with Asian philosophies and spiritual consciousness. The historical moment involving The Artists Village has come to be commonly accepted as a turning point in Singapore's contemporary art history.

I never officially joined The Artists Village as a member, but floated around it, especially in the vicinity of The Substation and National Museum Art Gallery. My memories of this time remain like a visage from a dream. For example, I recall being there in 1991 when Vincent Leow arrived at the National Museum Art Gallery wearing a sarong and carrying a briefcase that contained his bottled artist's urine, to give what I would refer to today as a 'performance lecture'. The 'lecture' became slightly heated when the validity of Leow's art was challenged by several artists present. This event was part of what to me was an eye-opening exhibition called A Sculpture Seminar (28 May-9 June 1991), organised by Tang Da Wu and The Artists Village. In that time, I also remember encounters with the 'villagers' who moved around and arrived at art events in a group, appearing as if they were a congregation.

You curated the LOCK ROUTE exhibition at Gillman Barracks earlier in the year. There has been much discussion about how Gillman Barracks could better galvanise the city's community and improve attendance. How do you think this could be done, and to what extent do you think events like LOCK ROUTE are essential to engaging new audiences for the arts in Singapore?

So much trust came with the commissioning of LOCK ROUTE by NAC [National Arts Council], EDB [Singapore Economic Development Board] and JTC [Jurong Town Corporation]. I was not yet a part of Chan + Hori or any other organisation at the time. I had to quickly form a team to produce, manage and deliver the international project within three months of my appointment. The curation was made deliberately loose and welcoming, and allowed room for navigation by the novice.

With the partial closure of Singapore Art Museum for its revamp, Gillman Barracks is now presented with an opportunity to rise through more curated contemporary art programmes. The rich historical landmarks around Gillman Barracks provide a great premise for engagements up to the scale of a biennale.

You worked with Natalie King on What happens now?, the Public Art Melbourne Biennial Lab (17–23 October 2016). The title of the Biennial Lab was derived from a Jenny Holzer slogan and was part of her 'Inflammatory Essays' from 1979. Holzer has described her work as intending to provoke a passive audience. To what extent do you see art as having that role: to provoke viewers?

For some time now, I have deliberated whether the impact of provocative artworks parallels that of the cinema. Well-executed cinematic craft is often able to disrupt the psychological and physiological space of the typical cinema-goer, even if only for a brief period. As an example, one could return home with sudden fear of a lurking ghost after watching a horror film. Do provocations from art operate in the same way—with acrimony and temporality?

Provocative or 'ambush'-type strategies towards audiences are normally calculated and deliberate. As a curator, it is a method I employ occasionally to jolt the viewer's attention. At the same time, I believe that to provoke is not necessarily to disrupt or offend. It could be a means to inspire ways of seeing, complement everyday experiences and instigate dialogues. One should bear in mind that apathetic audiences can be provoked, but not necessarily converted.

As Chan + Hori's curatorial director, you have spoken about the role as allowing you to pursue the idea of provoking relational change between art galleries and public institutions. Can you discuss this further? How might one address the inherent conflicts of interest in this possibility?

The memory of my curatorial role in artist-run initiatives and public art institutions is still fresh and relevant to what I do today. But most importantly, I always place artistic vision and quality of engagement with audiences at the core of my curatorial premise. And by artistic vision, I mean both the vision of the artist and my vision as curator.

Private art galleries, like private art foundations and museums, are not establishments where artistic integrity and originality are forsaken. Even consumer brands offering lifestyle choices, utilitarian products and services strive to innovate and serve consumers with integrity and responsibility. I do not see why commercial art galleries should operate as outlets offering pure retail and curatorial programmes inferior to those of public institutions. We can observe today how the typical public art institution is caught in a populistic complex or administration-driven mission to justify their existence and, more significantly, their consumption of public funds. Museum directors and curators of public institutions also increasingly appear to straddle cultural scholarship and the pressure to create mass-accessibility framed by strategically designed and fashionable public relations exercises.

Within the confines of social ethics, private entities are at absolute liberty to explore and engage with the constantly evolving attitudes towards artistic practice and its place in society. The combined roles and exposure conveyed by events such as art fairs, auctions and product collaborations with brand patrons have provided a foundation and, unsurprisingly, driven public awareness towards art and artists into our daily experience and social conscience. Critics of commercial entities should be more conscious of this.

I believe that the role of the private and public institution should not be totally compartmentalised or divorced from each other, as they are in truth interdependent. For example, the professional administration, promotion, inventory and legal management for a living artist is typically the remit of private agents.

Can you tell me about your vision for the gallery's programme, and how you propose working with these artists, perhaps by way of specific examples?

We are building our relatively new Chan + Hori brand with deeper processes and curatorial choices that look towards the future. For our exclusive artists, our immediate interest is the reinforcement of their individual art practices. The progression of local visual arts is also of interest to us. Here, we are committing ourselves to ideas that contribute to capacity and capability development. As an example, we constantly seek to create opportunities for and work with emerging curators, and we pursue partners to explore possibilities and support projects outside of the gallery space, all while we continue to cultivate dialogue with patrons and collectors. —[O]