Prateek and Priyanka Raja: Gallery as Incubator

Prateek and Priyanka Raja. Courtesy Experimenter.

Prateek and Priyanka Raja. Courtesy Experimenter.

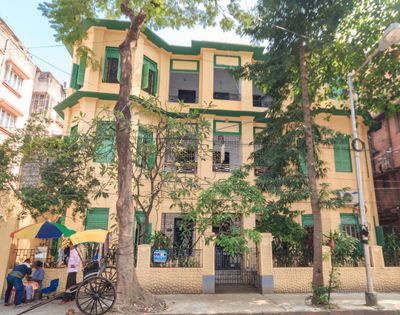

Founded in 2009 in Kolkata by Prateek and Priyanka Raja, Experimenter is more than a gallery—it is, as the Rajas describe it, 'an incubator' for a 'plurality of expressions'.

The gallery not only stages an exhibition programme featuring critically acclaimed artists including Bani Abidi, Moyra Davey, CAMP, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Prabhakar Pachpute. In 2010, it staged its first Curators' Hub: an annual three-day gathering that explores and debates developing discourses in curatorial practice and exhibition-making.

The Curators' Hub has been a core component of Experimenter's operations. Recent participants include Anita Dube, artistic director of the 4th Kochi-Muziris Biennale (12 December 2018–29 March 2019); Lydia Yee, chief curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London; Zoe Butt, co-curator of Sharjah Biennial 14 (7 March–10 June 2019) and artistic director at The Factory Contemporary Arts Centre in Ho Chi Minh City; and founding director of SAVVY Contemporary—The Laboratory of Form-Ideas in Berlin, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Since 2016, the Hub has been live-streamed, with over 20,000 people participating via live web streaming in 2018 alone.

As a centre for knowledge production, the gallery has since expanded into publishing, with Experimenter Books founded in 2016 to publish artist books, monographs, and book objects. Recent publications by gallery artists include Bani Abidi's I Love You (2019), an editioned flick book showing people mouthing 'I love you'; Aveek Sen's Art & Life: 21 Essays (2018), which showcases writings by the artist accompanied by photographs by the artist; and Ayesha Sultana's Form Studies (2017), in which the artist's architectural studies are collated to offer insight into a practice grounded in abstraction.

In 2018, Experimenter furthered its mission to make 'the gallery an active space for learning rather than a passive space for viewing' by establishing the Experimenter Learning Program, which was conceived as a year-long constellation of workshops, salon-style classrooms, symposia, and lecture-performances that ties into the Experimenter Juniors' Program as well as the Curators' Hub.

As the Rajas note in this conversation, which takes a deep dive into Experimenter's evolution, the gallery was primarily created as a sustainable space to think about art; rooted in the context of Kolkata and South Asia more generally and its connections to the wider world.

More recent initiatives include the establishment of Outpost, an iterative exhibitions programme that unfolds in disused spaces around Kolkata, and Experimenter Labs, which consists of projects designed to further the gallery's creative network. Components include the online screening programme Filament; a platform for cross-disciplinary projects created for the online space titled Black Box; and Experimenter Labs Reader, which presents guest-edited online anthologies.

Most notably, Experimenter Labs houses Generator, a co-operative art production fund that awards production bursaries through the year by open call, made exclusively available for artists not represented by Experimenter, which the Rajas discuss in the interview that follows.

This particular initiative speaks to the way the Rajas understand their practice as gallerists. Before starting the gallery, Priyanka worked in media sales for Procter & Gamble in India, while Prateek was a secondary market dealer who wanted to focus more on the art and the artists than on sales, without losing sight of the importance of sustainability. The two share a keen sense of responsibility when it comes to ensuring that an artist can keep working without compromising their artistic integrity. On his former life, Prateek says: 'I learned clearly what not to do.'

SBIt has been amazing to see the launch of Experimenter Labs, with the Generator co-operative art production fund providing some support for artists in light of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Priyanka Raja (PRI): The Generator project actually isn't that recent. We thought of it in 2017 or 2018, but our travels never allowed us to complete the legalities to allow for it to materialise until now. Here in India there is absolutely no government support—there's no art production funding from the government.

Kolkata is a city that allows for debate, in a way—it allows contrarian views, and for a certain sense of dissent, which is where our programme is rooted.

Prateek (PRA): One of our early conversations was with Bani Abidi, who is based in Berlin, about how grant-giving is such a power-disseminating activity, where an organisation or a group of patrons decide to give something to the artist, as if you are bestowing upon them this honour. This is a conversation we renewed, because we figured we would be closed for a few months, and very quickly we launched Generator, which came out with other initiatives from the Labs.

Generator is a unique model of funding that reconsiders the way that bursaries are disseminated—from the application process to their reception, and what purpose they serve. We created a framework that allows us to address all of these things in a decentralised way, so that we do not determine who gets what, but at the same time, we want to be part of the conversation of giving. We formulated it so that people can give whatever they want, and it doesn't go into a pool or kitty; we just match the donor's intent to the application.

PRIThese are micro bursaries that allow artists to continue working for three to four months. Initially we said it would happen twice a year, and of course with no ban on nationality or age, and then we realised there were so many good proposals, and so many people willing to pay, that we could do this every two to three months.

SBLabs also includes digital initiatives, like Filament and Black Box. But even before Covid-19, you were interrogating ways of using the online space to network internationally.

PRIWe've always been in Kolkata—we even opened our second space in the city. Our audience is very wide, and our artists are all over the world, so we've always worked with the idea of bringing dialogues here while connecting with the world through the internet or whatever other ways we could. We've been live streaming Curators' Hub for the last four years, from 2016.

SBYou have described Kolkata as a decentralised location of power, economy, and culture, rooted in the history of the historical trade routes that intersect here. How has the context of Kolkata fed into the identity and development of Experimenter as a multi-faceted nexus between public and private?

PRIExperimenter is like an octopus. It has one head that controls different tentacles. We have learned to work with limited ways of exchange and travel, which can be very difficult for artists. In Kolkata, we might be considered as something between a gallery and an institution. The programming is very institutional.

PRAWhen we started the gallery, we felt a very strong urge to locate ourselves in Kolkata, not only because both of us are from the city. We decided to open the gallery here because there are things about the city that make it unique: for one, its cross-cultural, decentralised, connective tissue.

It's important to exist in a place where the audience has the space to disagree and dissent and debate, and reference or cross-reference across history, literature, science, and culture.

Not only was Kolkata one of the very important colonial and pre-colonial centres of exchange, but it's also located close to the largest delta in the world, so it's where everything kind of comes together or flows in and flows out into a larger world. It was something we thought about consciously as being a node, not just ideologically, politically, or geographically, but even from the point of view of how people are here. This is a place where things are disseminating or have always disseminated. That makes a very different kind of audience, that is learned and able to cross-reference.

I'll give one example—the other day I went to a local store in an old house, and there were different scriptures on the wall. When I asked what these things meant, I was told that these scriptures could be seen on marble slabs above old doors in different rooms. The man who used to live there was a linguist, and he was interested in etymology and how words or letters were formed. So in this random store you have this quality of inquisition—a keenness to know and understand.

This eagerness to know—that's what made us want to locate our programme here, because ours is an inquisitive programme that wants to ask questions within the context of this incredible node where things are disseminating. Our artists also operate in a similar mode.

PRIWe're so grateful that we're here as opposed to anywhere else. Kolkata is a city that allows for debate, in a way—it allows contrarian views, and for a certain sense of dissent, which is where our programme is rooted. It's important to exist in a place where the audience has the space to disagree and dissent and debate, and reference or cross-reference across history, literature, science, and culture. Even online, people debate or ask questions during any of our talks, whether it's the Hub or the gallery. There are so many conversations, and it really doesn't matter who you are—when you're presenting, you are an equal.

SBThinking about Kolkata as a place where things flow in and out, the gallery becomes a space to process what's passing through and see what intersects, which relates to Curators' Hub as a space of knowledge production predicated on the simple premise: what do we know, and how can we learn?

PRIExperimenter was Prateek's vision—this is what he always imagined doing. When we imagined what this organisation would be, it was always supposed to be a space for dialogue. Of course, it's a politically agile programme, but it's not necessarily driven by politics.

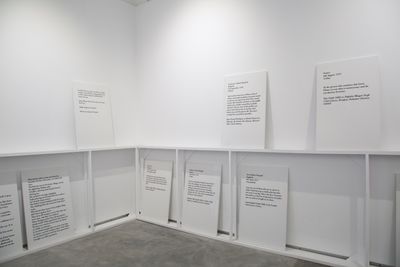

When we thought about curatorial practice, we realised early on that in India there is no platform to discuss one's practice at a very personal level. You present a show and there's a text around it, and there may be some talks, but there is no process or afterlife when it comes to thinking about what it means to make an exhibition.

Then we realised that maybe worldwide there isn't enough discourse around exhibition-making within peer groups—to learn together. We imagined Curators' Hub as a school where people could come together for three days and talk and learn from each other—to think about the future of curatorial practice.

In the first year, we called it the Young Curators' Hub, because we somehow thought that age had something to do with future thinking. We soon realised that there was a hunger to have a platform for these conversations. When we did the first edition, we saw relationships form, and now Curators' Hub has become something of a community. It wasn't designed as this big symposium. It's more like a close huddle.

PRAWe're not restricted by the trappings of art education, either. We're not scholars. We just did what we felt was right: to bring curators together to speak and share collectively. This was an urgent need for our audience and for us personally.

SBI'm reminded of Galeria Vermelho here, as they have a public component, including educational programmes, which their commercial enterprise supports. Founder Eduardo Brandão has said if you stop thinking then you stop selling, which is a nice way to think about how a gallery might engage with the market in a productive way.

PRIAt first, Prateek said he didn't start a gallery sooner because he didn't think it would work financially, and he didn't think he had it in him to navigate the market. Even today, he gets really nervous when he's talking with institutions. But for me, this wasn't a challenge at all. There are two of us directing this programme and we are both very different people—practically the opposite in terms of personalities. So when we talked about the idea of starting the space, I asked if he believed that we would have a really good programme, and he said yes. That's how it started.

I feel that there's enough scope for all sorts of programmes. You can be the big shiny Miami-based gallery, and you can also be a gallery in Kolkata that has this approach to thinking and engaging the audience in a certain way, yet exists within this hybrid market-driven world. Both have their space and it's important to stand for what you represent.

PRAThe reason that we're working with artists like Bani, is because they're constantly challenging these kinds of structures, whether it's through their work, their politics, or their relationships—we're always trying to break these structures.

PRIEvery five years the two of us take a few days off and then question everything we've done and try to break it. If we can't break it, it means it's good to stay. And if we can break it, we'll break it. So basically, it's about completely de-thinking—to step away. It's important to question everything, and think about the relevance of what you are doing for the time that you're in.

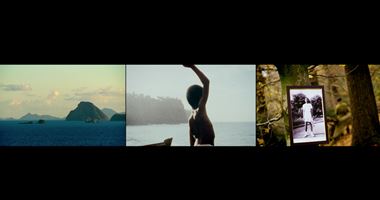

SBThe way you talk about structures reflects Experimenter's de-centred approach to exploring what it means to be global without losing sight of the context from which you operate. This reminds me of Naeem Mohaiemen's Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017) in some way, which looks back at a historical attempt at re-centring global discourses to incorporate broader perspectives.

PRANaeem is one of the crucial pillars of Experimenter. He operates in between the spaces of writing, activism, and making art, and he was also part of an early collective of artists and activists called Visible Collective and worked extensively on a project called Disappeared in America as a fallout of 9/11. We have been following his work since before the gallery started. He is extremely detailed and earnest—aware of himself, his own position and personal history, from the history of his family to that of the state, and at the same time he is aware of the complexities that we each live with our own histories.

The Bengal that Naeem and I grew up in are basically on two sides of the same coin; we have many shared histories, but also shared starting points that are politically divided, and that slippage becomes a different story for me and a different story for him. The seventies were a difficult time in West and East Bengal's history, and that reality is very recent. Although Naeem was born in 1969, and I was born in 1979, we still deal with that complicated history. Both our parents and their families grew up in what is now Bangladesh, so we have common ideas to talk about.

Even as far back as ten years ago, Naeem was talking about this complex historical moment. I could see the larger global historical arc that he was already addressing, but using it through specific points of his own history and the history of where he comes from. As you were saying, we become global from the point of where we are located. The loci of the global in today's world is both multiple and shifting. And that defines what Experimenter is, in many ways.

SBCould you talk about being global from the point of where you are located, in terms of how the gallery navigates the international art market?

PRIFrom the beginning, we weren't showing market-driven exhibitions. These exhibitions have consistently worked for us commercially, however, and we have placed works to collectors worldwide from our first exhibition—it didn't take much for us to pick up the phone or write or meet people. That's why over the past ten years we've travelled so much: to have these one-on-one relationships with supporters, patrons, institutions, collections, and foundations who believe in the artists we work with.

The loci of the global in today's world is both multiple and shifting. And that defines what Experimenter is, in many ways.

As you can imagine, it's been a consistent effort and we have always had the same aim—to make sure that work is placed correctly, not merely sold. The conversation we have with collectors in the preparation for these placements is equally important. You can't just walk into Experimenter and buy a work. It has to go to the right person.

PRAThis idea of reserving a work or placing a work comes from a respect for what the artist wants to say and an understanding of knowledge-sharing. It's not just about decorative acquisition. I am blamed by our team members for sometimes putting a spanner in conversations because I don't want to sell work to a lot of people.

SBCould you be as discerning at the beginning when it came to sales?

PRIYes, from the first exhibition. In the beginning, when we had all these crazy ideas but no money to sustain it, it worked to our advantage. Our overheads were less. But then we started adding art fairs to our programme.

SBWhich was the first fair that you participated in?

PRIOur first ever fair was Frieze. I remember they invited us and Prateek said, 'We don't do art fairs.' Then we realised, thanks to supportive colleagues who we respected, that we should accept the invitation. We only had three artists at the time: Bani Abidi, Naeem Mohaiemen, and Sanchayan Ghosh.

Later on, through acquisitions that happened via the initial conversations we had at the fair, we realised that the world is so much wider. Slowly we started developing various relationships, mostly institutional. Then we did Art Dubai, and now we do seven or eight fairs around the world. We complain about fairs and the time it takes away from family, but it has really helped us widen these relationships. We've been lucky to win the support of the most important private collectors worldwide to support all of our artists, to follow their trajectories. From the beginning until now I haven't seen a collector fall off the radar.

SBHow would you say these relationships benefitted Experimenter's educational programming?

PRAEvery time we have an idea, we have to figure out a solution to how to make that idea happen. For example, with the Learning Program—once we realised that the Hub was such an important place for people to learn and exchange, we asked how we could continue that. The upstairs floor in our second space is perfect for a salon-style classroom model, and we wanted to continue a full, year-long programme in which an individual working either within or outside of visual arts practice could come and teach three to five-day full-fledged modules. This is not available in our country; there is no art school where you can take a short course.

But this obviously also costs something—we have to pay people and fly them in. In year one, we didn't know how to make the Learning Program pay for itself, and we realised we would need some sort of seed funding. Hoor Al-Qasimi, who is a dear friend of ours and a patron and supporter of the gallery, said she would support a one-year starter project for 12 programmes. The first year, all the participants paid a small fee of 35 USD, which then became 50 USD, and now that's paying for the next courses.

SBYou mentioned Hoor Al-Qasimi, who leads Sharjah Art Foundation in fostering relationships across communities, whether local, regional, or international, by creating the conditions for different cultures and knowledges to come together. I wonder if you could talk about that from Experimenter's position?

PRII think that's the only way to be—if the programme is as multi-cultural as your location, and the artists as globally relevant in terms of their practice, there is no other way to do it.

PRAI think it takes us back to the idea of the delta, where the water moves its particles around any obstacles. You asked a question before about how we navigate the global commercial aspect of the gallery—this is how we do it. For us, context is key. If I can't create the context, then there is no in-road to the work, because it is not generally recognisable; this is a barrier.

When I say I am representing the artist, I am really representing the politics, the voice, the language, the medium, and the concerns of the artist to the outside world.

What I'm trying to say is that our programme is trying to expand that boundary. If I'm unable to create the context for an artist's work, we have to find ways to get around those obstacles and widen the frame. What I used to do in the earlier years, and still do once in a while, is meet with museum curators to introduce an artist's work into the realm of their thinking. It might sound odd, but we are not just dealers. I am the voice of the artist. I embody my artists' visions or thinking. When I say I am representing the artist, I am really representing the politics, the voice, the language, the medium, and the concerns of the artist to the outside world.

SBWith that in mind, what exhibitions do you have planned for the next few months?

PRIWe have a full range of exhibitions opening on site, because we really think that if the programming is consistent, people will come, and people have been making appointments.

Our latest show is a fantastic solo with Abhishek Hazra in our Hindustan Road space, showing until 30 September 2020. The exhibition places itself between different genealogies of dissent and the legacies of a graded, vertical society. The artist's multidimensional, research-driven practice refracts a complex cultural history through moving image, animation, language, performance, historical scientific documents, musical annotations, and spoken word. Hazra creates an environment where viewers can immerse themselves in multiple channels of visual and aural experiences. It will focus a lot on film, but there will also be live one-on-one performances with fixed appointment slots where the artist makes sudden appearances into the gallery via video chat. The onsite exhibition will concurrently show on Filament, our online film programme, so it can be seen by a wider audience until 20 October 2020.

We will also do Frieze and Art Basel's online viewing rooms, then we will open a big solo exhibition in the new space of works by Sohrab Hura (7 November 2020–2 January 2021). And then in the other space, we will open up a completely unexpected solo exhibition of Adip Dutta (5 December 2020–2 January 2021), who we have worked with forever, juxtaposing his work with his mentor and aunt-like figure, Meera Mukherjee—one of the most important women artists of her time, who would have been 97 today—to see how his way of seeing was defined by growing up with her.

SBThen you have the 2020 Curators' Hub, which will be the tenth edition.

PRIRight. Between 19 and 22 November, we will invite a curator who has participated in each year to talk about how time has influenced the way they look at their practice. It's a four-day Zoom event where one curator from every Curators' Hub will come back to speak.

For every Hub, Prateek sends a provocation email to every curator that we invite. He provokes them with a thought, but there is no overarching topic, because the whole idea is that it has to be a free-flowing discussion; it cannot be theme-based. So while there is never a theme, there is always an idea, and this year it's the idea of time.

PRAIt's just a way to start thinking. This year, we are not just looking at time as a durational aspect but also as a temporal aspect, in terms of what time means to do something then and to do it now. It's kind of reflective. A lot of what we do in the gallery is self-reflective—there's a lot of introspection, so time becomes a way of looking; a lens to consider what it means to curate and what it means to curate in the future.

SBLooking back on the evolution of Experimenter, what have been some of the biggest lessons that you've learned so far?

PRIWe have learned that we are at our best when we let things take time. Plans are made three or four years in advance; there's no sense of immediacy. Though our programme is very current—it's in the now—there's a certain sense or need to really calibrate. It takes some time to really develop a relationship with a work, an artist, or a programme.

PRAWe also value relationships, whether with our artists or patrons. I think relationships are at the core of what we do; that's what drives us.—[O]