Radhika Khimji's Gestural Acts

In Partnership With Experimenter

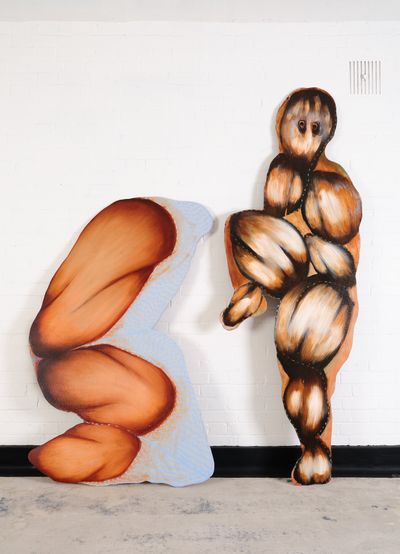

Radhika Khimji. Courtesy Experimenter

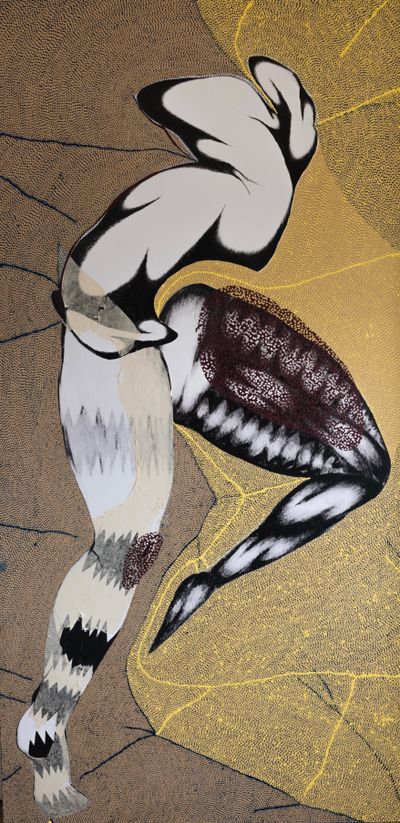

Radhika Khimji. Courtesy Experimenter

Central to Omani artist Radhika Khimji's practice is the body, conceived as fluid and transitory, and its relationship to space.

In reflection of this, Khimji's work combines elements of painting, sculpture, drawing, collage, photography, and embroidery to the point that the resulting object, often bearing some allusion to the body, occupies the overlapping space between different mediums.

After her studies in London at the Slade School of Art (2002), Royal Academy of Art (2005), and University College London (2007), Khimji has developed and presented her works in cities including Barka, New York, New Delhi, Mumbai, Vienna, and Beirut.

Safe Landings, her first solo show in her native Oman at Barka Fort (22–28 March 2010), featured the 'Shifters', a central body of works in Khimji's practice.

The series comprises anthropomorphic forms made from plywood and plexiglass cut-outs, often with a recognisably human pair of legs and abstracted torso painted in intricate, web-like patterns or washes of colour. Also known as the 'Cut Outs', the 'Shifters' assume various gestures and postures from the simple act of standing to the more laborious squatting.

In Safe Landings, some 'Shifters' were also connected to parachutes through the hole in the cut-out as in Cross legged 2, or the holes punched into the plywood of the crouching figure in Horizontal Right (both 2010).

Draped over the walls of Barka Fort, a historic site in Oman, the parachutes share with 'Shifters' a state of ambiguity. At once a painting, drawing, as well as a sculpture, a 'Shifter' defies easy definition; the parachute, having flown from elsewhere, could be a welcomed arrival or an intrusion, and an attempt to return home or take shelter, a dual symbol of hope and threat.

Parachutes also made their ways to the 6th Marrakech Biennale (24 February–8 May 2016) appearing draped over the historic El Badi Palace and Koutoubia Mosque.

Added to the connotations of arrival and escape of the parachute were the historical and political specificities of their sites—the now ruined palace, built in the late 16th century to celebrate a victory against the Portuguese, and the largest mosque in Marrakech—and with them the narratives of displacement, warfare, survival, and sanctuary.

In the past few years, Khimji has expanded the breadth of her materials, introducing photo transfers at her solo presentation Becoming Landscape at Krinzinger Projekte (now Krinzinger Schottenfeld) in Vienna (5 July–1 September 2017).

Emerging from her two-month residency at the gallery, featured works such as It's a deep dark floating and Rust in the System (both 2017) saw the artist paint opaque silhouettes suggestive of the human body over photo transfers of images taken at construction sites in Oman.

The collaging of knitting, drawing, painting, photo transfer, and sculptural forms made up the works in Over, Through and Around, another solo exhibition at Beirut's Letitia Gallery (28 February–11 May 2019).

A folded piece of knitting provides the background and frame for a wooden panel in The Great Escape (2018), which depicts an ambiguous grey landscape of an architectural structure in the distance. Laid over the landscape are translucent triangular shapes in red that are, upon closer inspection, revealed to be a pattern of small, intricate dots.

The gesture of creating the dots, whether with a paintbrush or punching holes into a surface, has a long history in Khimji's work. The dangler (2008), a three-metre-tall aluminium sheet suspended from the ceiling, is perforated with holes from its centre to the irregular edges.

The dangler is among Khimji's earlier works at Adorning Shadows, her current solo exhibition at Experimenter in Kolkata (23 October–24 December 2021), alongside more recent works showing her characteristic bodies.

In this transcribed conversation, which took place over Zoom on 28 November, Khimji discusses with curator and art historian Reem Fadda the 'Shifters', gestural acts and their ritualistic nature, the body and its parts, and space.

RMI understand that your practice started from an identarian-like moment?

RKBeing Omani-Indian almost feels like I am possessed by a certain 'look' or trapped in a certain category that erases all the other nuanced feelings and thoughts I am grappling with.

It felt disempowering to me on some level. I think it's interesting that in different scenarios, identity can feel either very empowering or disempowering. There's a reason to state it, and there's a reason not to state it.

RMLet's speak about the 'Shifters', because it's one of the building blocks of your narrative and your artistic practice. These genderless, biomorphic forms are very humanistic, but at the same time, not. They seem limbless, and sometimes they seem to inhabit a void, but they're also present and movable.

RKThe 'Shifters' came out of collages I was making about not being able to contextualise the body—a theme that has always been very present in my work. I'm constantly thinking about how one describes, rather than depicts the body.

I'm not making paintings about what a body looks like, but what it feels like to be in the body, and all the discomfort and space it inhabits. It's a reaction to a possessive and oppressive gaze; of movement and gesture that is conscious within this context of body.

I was making these collages out of different fragments from different body parts that initially originated from icon paintings. I learned how to paint a specific icon painting tradition from Nathawara while I was a student at the Slade.

The dots were a mark I used, because it was the visualisation of a human gesture onto the picture. I thought that's something I could expand on because of its human, ritualistic element.

I'm not making paintings about what a body looks like, but what it feels like to be in the body, and all the discomfort and space it inhabits.

That was one element that came into the collages. Another aspect is the abstracted body parts that got distorted away from the dress and costumes of the miniature works I was researching. These distortions and ritualistic gestures drew me to the body and dance.

I read the writings of Yvonne Rainer. Her writing in The Mind is a Muscle (1968), that a gesture could be picked up and put down, was very formative in my diagrammatic approach to the body's actions in space.

Gestural acts are central to my practice. The gesture of the dots, the placing of jewellery, and iconic ritualistic practice are all different types of performed gestures. It is also about movement, because a lot of the gesture in the 'Shifters' came out of sculptures with titles like Sit down, Stand, White standing, and Green standing.

They're all absurd in some way. They have a language of repetition and difference, and there's something really awkward about them. They're also highly sexualised.

RMThe sense I get with these 'Shifters' is that they are transient. They feel like they're in between bodies. They're like shadows that have merged together. I know that you always reference space across your works—architectural space, but you also explore time and motion.

What's it like to be you, Radhika, in your studio? How do you start your day?

RKI wish it were different, but I have a constant dissatisfaction with material, which probably keeps the motor going. I wake up and it takes me about two hours to start working.

There is a lot of getting up, eating nuts, sitting down, getting up, making tea, sitting down. It just takes me such a long time to settle. This is a daily practice. No matter how much I meditate, there's still a resistance that I constantly have to fight, because it's a vulnerable process.

It's definitely not easy always to get into this space of feeling comfortable enough with the self to start working.

RMYour work has a double dimensionality—there's never one right side or one left side, which is fascinating. I'm interested in your process of dotting and making embroidery—there's a cyclical element to them both. We see these shapes that are halos or circular, ingrained voids.

RKThe torso of the icon, which is full of jewellery, feels like a density of space, and I have always been drawn to that build-up of volume over a figure. I think that comes with a double-sidedness or a multilayered facet.

I've been fascinated with watching a mark cover up an area to veil and reveal it at the same time. There's a physical hovering over a zone of the boy or image, which feels like an energy zone, or a portal to another space.

All the work just happens through the process, partially because I'm never satisfied. These halos also happen due to areas in the works I would like to cover because they need some resuscitation.

This is how the collages came about, too; I used a lot of pencil, and the drawing would get really dirty since I worked on it and that would not be satisfying. So, I would cut it out and make a shape and then stick it down to a panel.

Later I thought, why am I sticking them within a rectangle, if they're meant to be these free shapes? That's when they became cut-outs looking for their own context, wherever they went.

All of these things happened through an interest in building. I'm very interested in construction sites as transient places where things happen in process. For me, when a work is finished, it's almost dead; my work in the process is over.

Like a contractor, I sign off on the work, hand it over, and then I don't know what my role is anymore.

RMI wanted to ask you about how you think through space and architecture. They are present in every work that you do. How do you feel you want to inhabit that kind of space?

RKI think there's an unfulfilled performer in me that hasn't and maybe will never live in my body, but it's a part of me. I think that was me as a kid. I was always dancing and there's this energy in me that just always wants to perform.

As soon as the work stops, it almost feels like a lie to explain and describe what it is, because they are so process-based and come out of a compulsion to make.

RMWe've danced together a lot.

RKYou know this side. I think we both might have an inner wolf perhaps.

RMA lot of your figures are dancing, which adds to that poetic layer of your work. Even ideas dance, and I think that's part of the transience. The architectural element makes sense, because it's a stage that allows these bodies to dance freely.

RKA space where these bodies can act out a sequence of gestures that link back to a body consciousness or in-built vulnerability—almost an alienated feeling of shame and sexuality.

RMYou have spoken before about these bodies being genderless or hyper-sexualised, but they kind of want to be away from their sexuality. They don't want to be demonised with all of these stereotypes and assumptions.

This idea of shame and these degenerative ideas are also parcelled into the work. How much of it is biographical?

RKThey are biographical on some level. The work comes from me and my feeling of being in my body. However, that's a starting point, and the work has to transform away from my own inner world and go out into the world.

The work has to be less me, yet it had to be me to make it. I'm starting to be able to express these associations recently. There's a different part of you that speaks about your work and a different part that makes it, and there's a huge space between those two poles.

As soon as the work stops, it almost feels like a lie to explain and describe what it is, because they are so process-based and come out of a compulsion to make. I don't have an agenda. I have a private practice that takes shape and root in the studio and has a different life when it crosses the threshold and goes on to live in the world.

In this show, there's a piece called The dangler, which is a white perforated aluminium sheet that holds its space. I think it's quite brutal. It's sharp and tends to scratch anyone who tries to piece it together and hang it up.

During the show at Experimenter, it was the first time I could articulate that this dangler is actually a labia. I made a conscious choice to be more articulate, and stop hiding behind metaphors.

RMSometimes we don't see the body at all, and that's something that I wanted to talk to you about. When the body is absent, in that realm of abstraction in your work or in the notebooks, what are we looking at?

RKThe landscape is a kind of inner world. I'm very interested in hypnosis, and the way one can access a subconscious space through the process of hypnosis.

A lot of the pieces I have made allude to that space and the hope to resolve situations no longer existing in the present but that are not fully complete. In that sense they are talismans and exorcisms made with the desire to resolve narratives long passed.