Same old, brand new: Art Basel in Hong Kong

Three is a lucky number in Chinese, since it is practically homophonous with “birth.” This is fitting when it comes to Art Basel in Hong Kong’s third edition, which launched this year with a new director (Adeline Ooi) and new dates (March as opposed to May). Three years on, the transition from ArtHK to ABHK feels complete. With 233 galleries from 37 countries and territories (half of which have spaces in the Asia region), 2015 was the year Art Basel’s third fair fully landed. Indeed, this fair was so much better than its previous two editions that there isn’t enough space to point out all the works and trends that stood out. Gone were the gaudy flowers and pop-depressive skulls that seemed to clutter the uneven floor last year—even the Buddha references took on a more subtle, or meta, approach. Take Saint Clair Clemin’s Buddha Merengue, 2014, at Paul Kasmin, a marble-rendering of a Buddha whose basic form appears whipped out of cream, or Gagosian’s inclusion of Nam June Paik’s Golden Buddha.

Inserting some further and local spirituality to the mix was Dane Mitchell’s Fourfold Threshold: a large, floor based sculpture, which the artist produced for Alexie Glass-Kantor’s Encounters. Mitchell invited a local ‘Villain Hitter’—who practices a form of sorcery specific to Hong Kong (which has been tentatively placed on the city’s heritage list)—to cast an auspicious spell for the fair. It must have worked; sales were buoyant, the collectors came, institutions were present, and the art was awesome. Hell, even Susan Sarandon came for a visit.

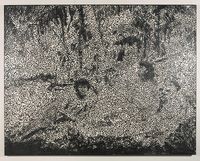

Dane Mitchell, Fourfold Threshold, at the Encounters sector. Courtesy Hopkinson Mossman and Art BaselAs a whole, ABHK felt balanced: light, playful, yet considered. Walking from booth to booth and hall to hall, one could sense an electric ripple, possibly caused in part by the way galleries sought to expand on the common tropes of the market place in surprising and often refreshing ways. Consider the forms of figuration on view, including Tobias Rehberger’s naughty camouflaging of a Japanese shunga scene Utagawa Kunisada Shiko no nagame 1829 I-III, 2015. The artist used clever pixilation to emblazon the image over a large wall at Galerie Urs Meile, out of which flower pots similarly pixelated protruded (with one flower pot standing on its own in front of the wall on a clean white pedestal). There were more traditional figures—such as Zheng Fanzhi’s Portrait 08-2-1, 2008, at Acquavella—and negations of such figures, like Mamma Andersson’s haunting Mimicry, 2014, at David Zwirner, in which bodies are presented as white negative spaces against a rose-coloured background. Classical updates were on show too, from Matthew Darbyshire’s CAPTCHA No. 21 – Doryphoros at Herald St to Claudio Parmiggiani’s plaster cast of a kouros, Senza titolo, 1995, at Meessen De Clercq. There were indirect suggestions of the body, from Marianna Uutinen’s Tits, 2014, at carlier | gebauer—seemingly comprising of breasts imprinted onto the canvas—to Neïl Beloufa’s Love ones yogi body, 2014, at Mendes Wood DM.

Tobias Rehberger, Utagawa Kunisada Shiko no nagame 1829 I-III, 2015 at Galerie Urs Meile. Photo: © Anakin Yeung & OculaAs far as crowd-pleasers went, the unequivocal winner was Sam Jinks’s life-like sculptures of a kneeling woman and a man carrying a limp corpse (in the manner of the pietas) at Sullivan & Strumpf. Though mention must go out to the brave introduction to Turkish performance artist Nezaket Ekici courtesy of Pi Artworks, where Ekici performed—wearing a white negligee and kissing a canvas with red lipstick—for the fair’s duration.

Nezaket Ekici performing at Pi Artworks, Art Basel in Hong Kong. Courtesy Art BaselOver at White Cube, Rachel Kneebone’s 2014 porcelain sculpture of a pile of bodies slumped in a heap was aptly titled when thinking about the context: Driving the Blind Excess of Life to the Very Edge of Death. The reference to what some call our inherent, natural and animal instinct as human beings was lightened this year by the addition of animals as a popular subject. Works included Yang Maoyuan’s bloated horses at Encounters, Paola Pivi’s pink-feathered polar bear at Galerie Perrotin, Tell me when you're ready, 2014, Chen Qiulin’s wooden animals at A Thousand Plateaus Art Space, and Herbert Brandl’s bronze wild cats at Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder. Death, as much as it drives us, is also an affirmation of life.

Paola Pivi, Tell me when you're ready, 2014 at Galerie Perrotin. Photo: © Anakin Yeung & OculaPerhaps this is why Wang Keping’s totemic forms of a man and woman carved out of the same tree positioned in front of Xu Longsen’s giant landscape scroll, Beholding the Mountain with Awe No. 1 at Encounters proved such calming inclusions. The pairing carried viewers to the source of much contemplation: the landscape, or, as Nilo Illarde would have it, the landscape of painting (or more broadly, representation). Showing in the Insights sector, Ilarde’s Faulty Landscape, 2002-2015, turned the Artinformel booth into a giant homage to painting through its materials—a mountain of paint tubes, for instance—with the following text written in colourful letters on the wall: “WE WITNESS PAINTERS MOVE FROM THE PAINTING OF LANDSCAPES TO THE LANDSCAPE OF PAINTING.” It was a booth that recalled Kilian Rüthemann’s work in RaebervonStenglin gallery in the Discoveries sector: eight bright outsized paint-sticks stood in the booth, one wall of which had been covered with lines presumably produced from these sticks, alongside four steel sheets hand-rolled to form huge columns and placed against said wall.

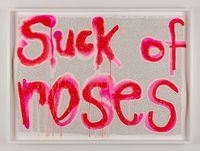

Ilarde, Faulty Landscape, 2002-2015, at Artinformel, Insights sector Art Basel in Hong Kong. Courtesy Art Basel. Both installations point to a kind of exploration not only of painting, but also the environment within which painting is shown, like the art fair. This was underscored in Karmelo Bermejo’s Fiscal Oil Paint series presented by Carroll/Fletcher in Discoveries: a work that comprises a number of monochrome paintings rendered with layers of glaze to look like surfaces coloured with standard manufactured oil paint, with the text “Undeclared Income” viewable only from certain angles. Fiscal Oil Paint invites the gallery and the buyer to refrain from declaring the sale and acquisition of any of the paintings: a savvy nod to the market and a departure from less subtle messages, like Yan-Pei Ming’s Autoportrait à un Dollar at Thaddaeus Ropac (a skull positioned on a dollar bill), or Ed Ruscha’s new text work that reads “DEAD MALLS” at Gagosian.

Karmelo Bermejo, Fiscal Oil Paint series, at Carroll/Fletcher in Discoveries sector, Art Basel in Hong Kong. Photo: © Anakin Yeung & OculaYet, in actual fact, there was nothing dead about this art mall, even if Quartz asked (as does many a publication each year) whether art fairs like ABHK are killing art. Indeed, there was much to see that pointed towards new direction, or opened things up to greater interaction—Andrea Rosen’s offering of an endless stack of red posters by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Untitled, NRA- National Rifle Association, 1990), for instance, was a wonderful and generous introduction to the essence of Torres’ practice to a local audience. Rather than stagnation, there was a sense of a continuous flow: one that was reflected in the delicate thread drawings suggestive of human movement by Do Ho Suh at STPI, or Julian Opie’s LED screen panels of people walking at Kukje/Tina Kim and at Lisson (as always) presented on a loop: non-stop, but steady.

Kukje Gallery Booth at Art Basel in Hong Kong 2015This made the presence of two booths focusing on the circle fitting thematic insertions. Athr Gallery titled its presentation Why is the Power Button Always a Circle? Featuring Dana Awartani, Ayman Yossri Daydban, Ahmed Mater, Seckin Pirim and Nasser Al Salem, the curatorial intended to look at the circle as a symbol of movement, time and perpetual motion. Meanwhile over at Insights, Charwei Tsai presented watercolor and ink on rice paper swirls framed by the title We Came Whirling Out Of Nothingness at TKG+, pointing to how human perception parallels the revolving, and repetitive, forms of nature.

These circular perspectives made Keith Haring’s Three Dancing Figures at Gladstone and Tassos Pavlopoulos’s tongue-in-cheek update of Matisse’s Dance at Kalfayan, Bye Bye Matisse, 2008—a motely crew including a thief, a clown, and a gasmask-wearing suit—feel all the more apt when it comes to the art world’s global flow. Think about the movement within Art Basel’s halls, and the three-city cycle this fair now operates. In this dizzying circulation, there is a need to remember that a cycle need not be frenetic: it can be slow and meditative. Nor does every repetitive cycle have to be a trap: we do not have to end up like those anonymous men filmed from behind pushing a sheet metal structure on a loop in Chen Chieh-jen’s video installation People Pushing, 2007-2008, at Lin&Lin Gallery.

The thing about cycles is that they do not always lead us back to the same starting point; often they can take us just beyond where we began. This was articulated quite clearly in Cao Fei’s video installation on Hong Kong’s ICC building, on which the artist projected a video game that always ended with “You Win” alternating with “Game Over” in flashes. The project was titled: Same Old, Brand New.—[O]