Christopher K Ho’s homecoming at De Sarthe: CX 888

'Why cover the same ground again?' Odysseus asked in The Odyssey, one of literature's most lionised tales of homecoming. His question is echoed by New York and Telluride-based artist Christopher K Ho in the presentation CX 888 at de Sarthe Gallery, which explores the complexities of departure and arrival through a Hong Kong-specific lens.

Installation view: Christopher K. Ho, CX 888, de Sarthe Gallery, Hong Kong (1 September–15 September 2018). Courtesy the artist and de Sarthe Gallery.

As the end of the Trojan War marked Odysseus' journey home, CX 888 signifies Ho's return to Hong Kong. Having left Hong Kong for Los Angeles as a child in the late 1970s, the artist is preparing to move back to his birthplace almost four decades later; he considers this presentation—his first in Hong Kong—a first step.

Such adult homecomings are not uncommon here; Hong Kong has experienced significant waves of outward migration, particularly in the midst of anxiety leading up to the 1997 handover. Accordingly, the grown children of the diaspora often arrive back in present-day Hong Kong with uncertain dual identities; are they Hongkongers, or do they bear the mark of the country their parents landed in? What does it mean to be of a place you once departed?

CX 888 is the result of a five-week residency at de Sarthe, during which time the curatorial non-profit Forever & Today (co-founded in New York by Ingrid Pui Yee Chu—another child of return trans-Pacific migration—and Copenhagen-based Savannah Gorton) invited Ho to share the Wong Chuk Hang space as an office and studio. The public was invited to visit the curators and artist during standard opening hours, making apparent the ordinarily invisible artistic and intellectual labour of exhibition-making.

Ho uses Cathay Pacific's daily Hong Kong-Vancouver-New York flight—CX 888—as a symbol of his investigation. The route serves as a familiar means of departure and return for the many Hongkongers with ties to Canada and the United States. By the time the presentation opened on 1 September, rows of blue deck chairs arranged in the far corner of the gallery were bisected by a long carpet, mimicking an airplane aisle. Two single-channel monitors on the wall above them flashed Cathay Pacific's brand colours; teal and maroon oscillated in dactylic hexameter, the poetic meter used by Homer in The Odyssey.

The presentation consists of several such coded and fragmented gestures, the largest of which is the excavation of more than half of the tiles from the gallery's floor. The remaining tiles constitute a pattern that loosely approximates an aerial view of Hong Kong's coastline—perhaps seen from an airplane before landing or after takeoff—while the displaced tiles are arranged in stacks simulating former British defence buildings. Assisted in the removal of the tiles by artist Lee Lee Chan, Ho considered the laborious process akin to sweat-labour by which he could 'earn' his sense of belonging in Hong Kong, underscoring an uneasy sense of mis-belonging common to the experience of, as Chu and Gorton write, being both an insider and an outsider.

Exemplifying such in-between-ness and placed on a stack of tiles is an intimate grouping of photographs taken at his family's Miramar hotel in Hawaii, which Ho visited on stopovers between Hong Kong and the United States as a child. Held down by rocks inherited from his grandfather's collection, the images from the midway destination suggest intermediary possibilities amid disparate states of being.

Nearby, an uncanny melody emanates from a rock—or a speaker painted to look like a rock—that plays a rendition of So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (the song the dolphins of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy sing before leaving earth to its doom). Recorded by an erhu player in Hong Kong, Ho uses the song as a trans-cultural stand-in for his present-day farewell to America.

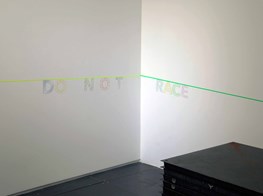

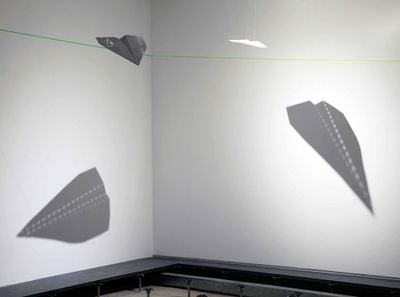

The personal bent of the presentation, which the curators call a 'psychological landscape of memory', manifests in DO N O T RACE (2018), an undulating line of tape that traces along the wall of the gallery. The line tracks Ho's changing mood during his last flight from New York to Hong Kong, with his oscillating emotions denoted in yellow and green. Reflecting the same hues are the swathes of fabric that Ho stretched and draped over boxes and objects such as a hammer, clamp and rock. Vibrant and sculptural, the fabric is dyed in emerald green and gold jewel tones; to Ho, these colours represent 'Chinese-ness', or the performance of such.

While numerous other objects and gestures are positioned thoughtfully throughout the gallery, pushed against a wall is a simple desk and chair, above which are pinned technical documents such as CX 888 flight plans, weather charts and cockpit diagrams—it appears as either the workspace of an anxious traveller or obsessive researcher. On the desk lies a blank Cathay Pacific boarding pass, stuck in a puddle of spilled coffee. With no date or destination, departure and arrival are purposely confused.

The public nature of the residency served the presentation well. With characteristic openness, Ho discussed his process over the course of the five weeks with a range of visitors that could relate to feelings of displacement in a globalised age; in this way, Ho's candid and considerate first project in Hong Kong was successful in that it resonated with the cosmopolitan art community he will soon join. Yet to borrow again from the lessons of Homer, when Odysseus finally reached home after one decade abroad, he found both Ithaca and himself changed—it remains to be seen, after four, whether or not Ho will find the Hong Kong in his memories still exists. —[O]