Fahd Burki: Minimalism Between Dimensions

It's not enough to say that Fahd Burki's work has evolved over the last five years—his shifting practice seems to be in a perpetual process of subtraction.

Exhibition view: Minutes before I fall asleep, Grey Noise, Dubai (19 September–12 November 2020). Courtesy Grey Noise, Dubai.

What began as a turn towards abstraction for the Lahore-based artist has moved to dissolution: a spare approach to pictorial space stripped of all ornament.

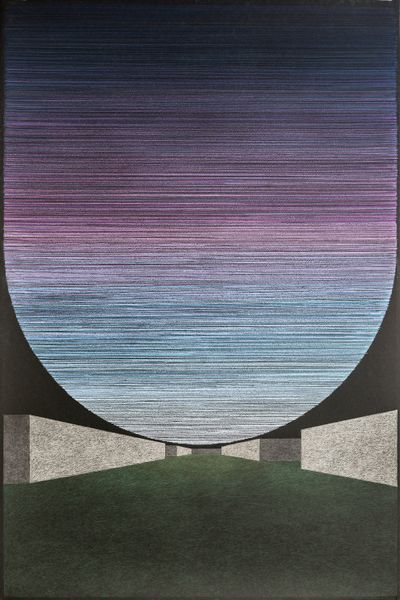

Gone are the graphic iconographies, floating geometries, and anthropomorphic totems, as seen in works such as Healer (2012), a post-human emoji-like collage on paper with flat black discs for eyes that sit atop an inverted triangle, inside a circle. Migrating architectural forms, like the intricately striated U shape rising above a perspectival plane of bare monuments in the utopic Seeking Eden (2014), have disappeared too, as have the grids.

Talking about Minutes before I fall asleep, his latest show in Dubai at Grey Noise (19 September–12 November 2020), Burki admits that he has shifted from looking at the sociopolitical world to taking an insular view.

Yet if the change seems sudden, it's because Burki works in such a way that disruption is met with a certain rigour. Take Dwelling (2020), a relief that belies its materials in Nintendo grey: what looks like the intricate plan for a modular structure in clay or rubber (instead of wood and acrylic), has gone through many drafts, but you wouldn't be able to tell.

During the past year and a half, Dwelling has evolved from a wooden frame without a solid centre, originally conceived in 2018 for Art Basel 2019's Statements sector, to a carefully modified plane of wood. 'I tried to get it to progress, but I came back full circle,' he explains. When the wood grain showed, he painted it a flat, matte grey, to insinuate the work's architectural dimension, the colour alluding to materials used for construction such as concrete or stone.

Indicative of his reductionist practice, Dwelling embodies an appealing neutrality. Its grounded structure gestures towards a functionality that's in stark contrast to the primitivist, science fiction leanings of earlier freestanding sculptures. The wood sculpture Optimist (2012), for instance, is a cross between a nonchalant robot and an obsolete digital device. In Residuum (2013), a deconstructed Perspex figure made of bars, cones, and other geometric shapes hangs onto a black tomb-like slab.

Burki is still interested in popular culture; but those references are just less visible in his work. 'Some of the errors in video games inspire me . . . If not coded properly, you can get stuck in a wall, which becomes an abstract image on the screen. It's an error called clipping.'

While he speaks of these online architectures as problems to solve, his sense of dimension has become material. Outlines of incomplete forms are now replaced with a vocabulary of compositions in counterbalance. In Parallels (2020), a pair of slanted lines offset each other. Framed by two strips of wood, they cut across the canvas, skewing the central blue line in a harmonious configuration. The beech bands form a parallelogram within the work.

This compartmentalisation continues with Affinity (2020)—a series of three pulse lines puncture acrylic gesso in sharp, open triangles that evoke rhythm, like intervals of a heartbeat.

These 3D reliefs were made in the past year, marking a moment in Burki's practice that locates itself between sculpture and painting, realms that were kept separate before. 'I wanted to make three-dimensionality more concrete in bevels, curved surfaces, and contours', he explains, 'and push my paintings from the subtle suggestion of dimension.'

At the same time, Burki also pushes his work to exist between dimensions, a conceit that began with his allusions to suspension in his Momentary structures and Five intervals exhibition at Grey Noise (8 January–10 February 2018), where carefully drawn lines appeared to float above scaled shadows, expressing tensions between flatness and volume.

Amaryllis (2020), a nostalgic composition of two single leaves placed in opposition, painted in clean strokes of sage-green acrylic, is the closest he gets to figuration in his current exhibition. 'As soon as the work starts looking too much like something, I go back to the drawing board. I never want it to be strongly suggestive of anything.'

It's difficult to explain how much richer Burki's distilled configurations have become in this striving towards an excavation of concept and adornment. With materials left bare in a journey towards restraint and calibration, away from big ideas and noise, Burki's work gestures towards that 'plane of thoughtlessness,' which he admits is an impossibility: 'How do you blank your brain out?'

Interestingly, the titles that Burki chooses create more of a narrative than the art itself. He tries not to attach too much meaning, allowing room for an audience to enter. This purist approach might leave viewers cold, but it also retains material residues that seem to exist outside of time and its decay.—[O]