Francis Ng: A Bit of an Anomaly

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH GILLMAN BARRACKS

Francis Ng has led many lives. A self-described 'low-tech person', Ng made a name for himself as a young artist with Delocating margins (2001), a site-specific intervention in a disused shophouse lot. A gesture both brilliant and brash in equal measure, it earned him his fair share of critical attention. What followed was a decade-long practice boasting conceptually and materially ingenious work—he was one of the youngest artists to represent Singapore at the Venice Biennale in 2003, he was shortlisted for the President's Young Talents (PYT) award earlier in the same year, and won the 2004 UOB Painting of the Year competition (in the photographic category)—before he eschewed art-making for architecture school in New York, designing and building a private home on commission. More recently, More recently, however, Ng has returned to art, achieving a comeback of sorts with a large-scale outdoor piece, ArteFACT; Unearthing Relics of the Future—an affiliate project of the Singapore Biennale 2016 (27 October 2016–26 February 2017), which was shown at Gillman Barracks, as well as a two-man exhibition at Pearl Lam Galleries, Contestation: Mass Openness 10 June–3 September (Dempsey Hill) and 10 June–30 September (Gillman Barracks) (2017).

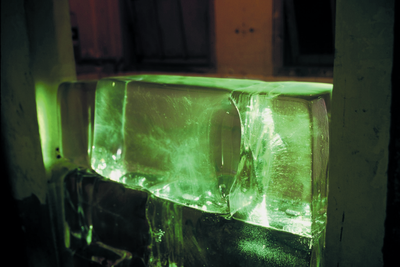

Francis Ng, Delocating margins (2001). Site-specific installation. Mixed media. Courtesy the artist and wowwowwow.

Let's begin with the basics. How would you characterise your practice?

I guess you could say that I'm a jack of all trades and master of none. I tend to see myself as just another artist.

Your work seems to encompass a broad spectrum of materialities and modes of expression.

My work is multidisciplinary, it shifts from one register to another. I realised early on in my education that I'm not very satisfied with working in any one medium. It's hard to put a label on my practice. My abiding concerns are space—both physical and mental—and, yes, ideas of materiality, ideas of matter, of form and formation and construction. I think of my work as a fulcrum, a point of support on which things turn. It's an object that makes sense there and then, in its specific time and place. I want to challenge our perceptions of history, of the world we live in.

You got your start in the early 2000s, before the art world here in Singapore radically expanded. Could you describe the beginnings of your career?

It was a different world then. I graduated in Fine Art from LASALLE College of the Arts in 2000, and then went on to the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) in Australia after receiving a scholarship from the National Arts Council. I was very prolific in the early days; I was thirsty to produce. I was also very much into photography. That's an interesting story actually: later on in my career, when I came to a point where I felt creatively stuck, I just went out and photographed what I call 'blanks', which is to say anything and everything, with little premeditation. I got bored working with just the camera, however, and went on to painting—though I eventually became weary of two-dimensional mediums altogether, and moved on to installation, which of course has defined my practice.

Are there any particular figures in your education who made an impact?

I studied with the likes of Ian Woo and the late, great Chua Ek Kay. Chua was a mentor of sorts to me, he really fired my imagination. His influence on my thinking as an artist was lasting. He did mentor me for the PYT exhibition in 2003, when I was a finalist, alongside Lim Tzay Chuen and others. I was exposed to Western art at LASALLE, but Ek Kay was the one who introduced me to Chinese ink. As a form of practice, I used to copy his ink works, stroke by stroke. That's how masters impart the technique to their students, even today. It was pretty didactic training and actually fuelled my desire to go crazy.

That's an interesting way of putting it. How did you go crazy?

Back in 2001—I was barely out of art school then—I created Delocating margins, my first major project, a site-specific intervention in a disused shophouse space on Loke Yew Street, across from The Substation. It was my introduction to the art world, or the art world's introduction to me, and it's the work that I'm still remembered for. I think of the work as a 'time piece', where time actually determines the physical form of the space and its contents, which were transient and changed and shifted as time passed. With this work, I saw myself as breaking away from traditional mediums like Chinese-ink and oil painting, both of which had been a big part of my training.

Tell me more about Delocating margins.

On the first floor of the space, I lowered the ceiling beams, littered the floor with chunks of tarmac I had salvaged from Victoria Street, and put up concrete walls and wooden scaffolding, even a wall of ice in a passageway. I turned the interior into a construction site. It was an exercise in dealing with space, and of course when working with a site like the Loke Yew shophouse, which dates from the 1930s, dealing with space is also dealing with history—the structure is a palimpsest. The project became a dialogue for me; it became about negotiating conflicting notions of private and public, internal and external, stability and instability; a whole series of dichotomies. I wanted to challenge the perception of equilibrium, the viewer's sense of the ground where they stand, oblige them to navigate real space made unfamiliar...it was a labour of love. The project attracted a fair bit of notice, especially from architects; Tay Kheng Soon and Raymond Woo stopped by. I was pretty thrilled.

Working with concrete seems to have remained a constant in your practice. Your latest works in Contestation: Mass Openness at Pearl Lam Galleries include quite a few such pieces, as did an early project, in PYT.

Yes, the family business is in construction, so my supply of material is assured! The PYT project at the Singapore Art Museum in 2003 came soon after Delocating margins and was also a site-specific installation. It featured a structure comprised of in-situ cement walls adorned with light fixtures, and was a continuation of my interests in space, site and materiality, and issues of displacement.

What was the PYT experience like?

It was intense. I really only had a very small window in which to complete the work. It was a very tense period.

Yes, 2003 was a busy year for you. You also represented Singapore at its national pavilion in the Venice Biennale with Displaced (2003).

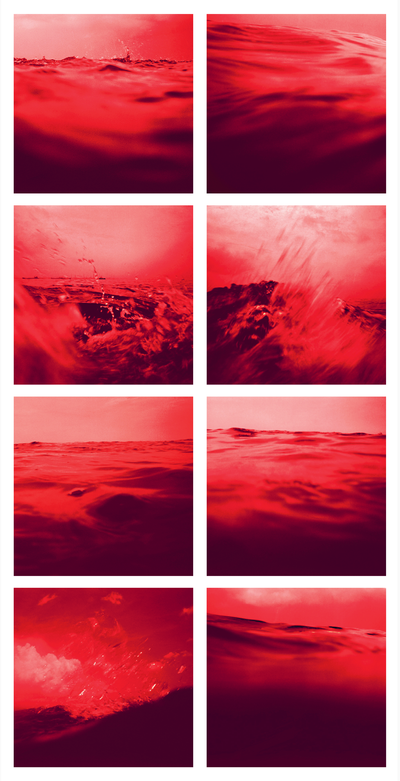

Yes. It was a group show. I was feeling dissatisfied with my output at that point. I went swimming in the waters around Singapore with a camera strapped to my body, taking eye-level pictures of the sea. The amorphous, surreal quality of the surface of the water was something else, it was like being transmitted pictorially to a different realm altogether. At times I was not even swimming, just floating and drifting along, letting the currents almost pull me out into the ocean, and shooting randomly. I wanted to capture that sensation on film, that exchange between the deliberate motion of swimming and the element of chance when I simply allowed my body to drift. The entire project was about that bodily exchange, about me coming to terms with my corporeal presence in an unfamiliar environment. It was about the desire to stay alive, a sense of struggle, of being at a loss, of being inarticulate.

It's your use of concrete as a medium that I find intriguing. The works at Pearl Lam Galleries represent a departure for you, with the deployment of concrete in wall- and floor-bound objects, rather than full-scale structural elements.

Yes. The invitation to show at Pearl Lam came after the exhibition of my Singapore Biennale 2016 work, ArteFACT; Unearthing Relics of the Future. The conversation evolved from there, and I had about two-and-a-half months to pull everything together. I thought I should try to do something new, but what is 'new' isn't new after all. It was me coming to terms with my practice. I immediately turned to cement, to concrete. On one hand, concrete is extremely predictable, it's easy to work with, yet I also wanted the works to have an element of chance. I thought about casting, and thought that reverse casting could be very interesting. Working in the reverse-casting process with plastic sheets, cloth, rubbish, et cetera, was liberating.

Of course, you also utilise concrete in actual building projects.

Yes, I have received architectural commissions. What I call Project no. 42 was actually a commission from a collector who enjoys my drawings and illustrations; I designed and built his home in the Upper Thomson area in Singapore. That was in 2011. It features qualities that are present in my work as an artist. The structure features a pronounced use of lighting to create shadows, to foreground the interplay of planes. I carved out a deep-set pool, and the whole house seems to be floating from afar. I see it almost as a painterly work.

I'm curious about your take on the local art scene. Let's talk about that.

Being an artist in Singapore is hard! We get lots of support here in Singapore, but that's a double-edged sword. If there isn't that level of support, what do we as artists do? Knock on doors? Maybe that's exactly what we should do: knock on doors, learn how to be savvier and more resourceful. We're almost too well-insulated here. There's no 'gung-ho-ness', there's little making for the sake of making things.

And how do you see yourself within the local ecosystem?

There was a greater sense of community back in the early 2000s, when I was starting out as a young artist. It's been almost two decades. It's a bit of a critical juncture in my practice at this point—how do I contribute further? What do I want out of my practice and how do I sustain my craft? I suppose it's pure stamina and determination. So many other artists I started out with back then have dropped out; perhaps fewer than ten people I know from those days are still making art. Even I took a pretty long break, from about 2011 to 2016. I was in New York at the Pratt Institute doing graduate work in architecture, which I didn't finish—the programme was very focused on computer programming and such. I got frustrated. It's easy to get side-tracked, being a creative person.

Any last words?

I really enjoy being a low-tech person. Maybe that's evident from my art. That makes me happy and satisfied within my very myopic understanding of how I function as a human being. In the greater community of people Facebook-ing each other every other second, I'm a bit of an anomaly. I like it that way. —[O]