Marc Camille Chaimowicz’s Camp Is Anything but Queer

Already well established with a myriad of shows under his belt, Marc Camille Chaimowicz is often described as an 'artist's artist', responsible for pioneering installation art long before the term 'immersive' became a press release cliché.

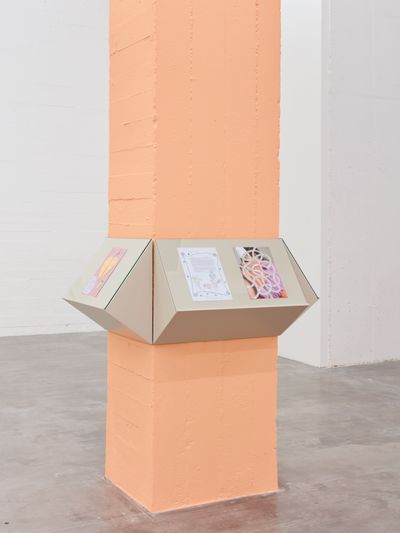

Marc Camille Chaimowicz, Celebration? Realife Revisited (1972–2000) (detail). Exhibition view: Nuit américaine, WIELS, Brussels (17 February–13 August 2023). Courtesy WIELS. Photo: We Document Art.

For Chaimowicz, art is not separate from life, but simply its stylised form. This theory is deftly evidenced in Nuit américaine (17 February–13 August 2023), his first major exhibition in Brussels at WIELS contemporary art centre.

For Nuit américaine, curator Zoë Gray pays homage to Chaimowicz's sensibilities by treating the show as eternally evolving, with three bodies of work—among them, two previously unseen installations—presented across three galleries.

The show begins with the installation and performance piece Celebration? Realife Revisited (1972–2000): a glitter-splashed, fairy-lit scattergun display of thrift-store discoveries and hotchpotch that has been exhibited prolifically in varied forms.

Shown in the first room, it's the perfect, disco-balled introduction to Chaimowicz for uninitiated Belgians; that, at least, appears to be Gray's reasoning. The walls are painted silver à la Warhol's factory, a soundtrack blares seventies classics by David Bowie, The Doors, and Jimi Hendrix, and strobing lights mean the room is always changing.

Add to this the glitter adorning paillette espadrilles, a cheap pleather bag, and other titbits, and one is faced with endless possibilities and narratives that unfold while walking the room.

Originally inspired by the May 1968 protests he witnessed in Paris, the installation harks back to Chaimowicz's days as a painting student at Slade School of Fine Art in London, where despite the school's esteem in the medium, he eventually decided to make installation. Upon returning from Paris, Chaimowicz set alight his undergraduate work and began defining his practice.

The philosophy the artist gleaned from the student protests is apparent across Celebration? Realife Revisited. Like Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari's concept of the rhizome—itself inspired largely by May 1968—the work takes on a rhizomatic structure, where all avenues or plateaus exist on the same plane.

In short, there is no didactic intention. Evoking a spectral affect, as if entering a disco while dissociating, the installation's composition underpins a narrative (or lack thereof) that is forever in flux.

As Gray says, the camp aesthetic is 'difficult to pin down because if you pin it down it stops being camp'. But while this installation's camp never succeeds to deliver a single message, one leaves with a comprehensive sense of Chaimowicz.

That sense continues in the second room, where The Hayes Court Sitting Room (1979–2023) memorialises Chaimowicz's old sitting room of over 40 years on a wooden stage, furnished with his own possessions. But rather than historicising his home in a like-for-like model, he depicts it with nods to its own inherent performance.

The flowers above his fireplace, for example, could not be transported from his old home in Camberwell, South London, to WIELS. Instead, alongside real cigarette burns in the carpet and discolouration on the wall where a Catholic cross once was, Chaimowicz cut up the exhibition poster, which features a photograph of their leaves, and placed them in a vase.

According to Gray, the artist didn't finish working on this installation until two days before the show's opening. Lighter and slower than Celebration? Realife Revisited, the sitting room feels both private and public, primed with careful assemblage and choice decorations.

An aesthetic picture begins to form. Chaimowicz's abstract motifs are printed on the wallpaper and cushion designs, while the signature palette of a baby shower peppers the space alongside restrained, mid-century-modern furnishings.

Chaimowicz's camp aestheticism is softer, effete, and without political charge. At most it could be queer, but were it to succeed, its allure would vanish.

This simulacrum, the most sombre part of the exhibition, offers glimpses of the artist's intellectual interests within existentialist literature—a book by Camus is strewn across a tabletop—but equally, the staging is completely apparent. It might be honest and homely, but it's also a little dressed up. After all, that's what a sitting room is: a balance of intimacy and showmanship to entertain yourself and receive guests.

Chaimowicz's camp aestheticism comes into full fruition with luxurious femininity in the third gallery, which features 40 collages housed in lecterns fixated to pastel-hued pillars. Dating back to October 2020, when the project began, the collages were sent to Gray at a regular cadence, arriving roughly every fortnight.

Based around the namesake heroine from Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary (1856), they document Chaimowicz's varied moods and obsessions during the throes of lockdown, when due to his fragile health, he remained alone. At the time of my writing, Chaimowicz is still isolating.

Composed as letters to Gray, the first collage outlines in handwriting the varied personas of Emma Bovary, such as 'Emma the enchantress', 'Emma lascivious', 'Emma in despair', or 'Emma (utterly) alone'. In one sense, it's the lonesome Chaimowicz wallowing—quite justifiably—in his isolation, but it's also the artist fabulating a more glamorous scenario beyond his own.

At no point do these works feel objectifying, however. Even where women are more explicitly depicted.

With whimsical borders that are drawn and painted, the collages were all made on his kitchen table, many using pages from fashion magazines. An act of diva worship, they fetishise the flourishes of femininity.

'Emma, ... ever desirous', reads the note at the bottom of one swirling purple collage, clustered with ballet shoe cut-outs, luxury earrings, flip flops, bijou trinkets, and bows. 'Whatever to wear to the ball? The opera, the gala, to whatever...', reads another work pasted with a lady in Chanel.

At no point do these works feel objectifying, however. Even where women are more explicitly depicted, such as in close-ups of lingerie. There's a romance at play, whether in the figure of the femme fatale or the longing lady, tired of a lacklustre life and dreaming of more.

Moving through the show, Chaimowicz is presented first at his most playful, then at his most performative, and finally at his most aesthetically indulgent. Yet throughout, the artist always feels slightly beyond reach.

'He's like the work: layered, complex, funny, and quite acerbic at times,' says Gray, who wonders whether it's a queer sensibility. But while the press release uses this term, it doesn't quite fit. Chaimowicz's camp aestheticism is softer, effete, and without political charge. At most it could be queer, but were it to succeed, its allure would vanish.

As Susan Sontag put it, 'Camp is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of "style" over "content", "aesthetics" over "morality", of irony over tragedy.'1 Chaimowicz might be suffering alone, but he's doing it in style. —[O]