Gwangju Biennale: Burning Down The House

Gwangju is only the sixth largest city in Korea but its history has become well-known to art audiences around the world through its provocative biennale, now a fixed event in the international art calendar. The Gwangju Biennale began twenty years ago specifically to commemorate the historic fight for democracy that took place in the city, known as the 1980 Gwangju Uprising. Now in its 10th iteration, the Gwangju Biennale has a radical mission to renew itself every two years, reinventing its curatorial framework while remaining invested in the city's vitally important political history.

Firmly rooted in the historical significance of the pro-democracy uprising that occurred in Gwangju, the Gwangju Biennale has continuously sought to reflect on the unique aspects of its particular regional landscape. This discourse has been a challenge for each curator of the biennale; the history can impose limitations, and the civil questions must be actively addressed in the context of the current global socio-economic and political environment. Jessica Morgan, the artistic director of the 10th biennale who is the Daskalopoulos Curator of international art at Tate Modern (and has just been appointed the director of Dia Art Foundation), borrows the American band Talking Heads' song, Burning Down the House, as the title for the exhibition. This well-known track from the early 1980s evokes the double significance of her biennale that, according to Morgan, 'explores the process of burning and transformation, a cycle of obliteration and renewal witnessed throughout history. Evident in aesthetics, historical events, and an increasingly rapid course of redundancy and renewal in commercial culture, the Biennale reflects on this process of, often violent events of destruction or self-destruction—burning the home one occupies—followed by the promise of the new and the hope for change.'

This curatorial hook is most powerfully embodied in the works of Lee Bul and Minouk Lim. These two important female artists were born in Korea just four years apart—Lee in 1964 and Lim in 1968. Lee's work is one of the first pieces to confront a visitor upon entering the biennial. In it she presents a costume and video installation playing the artist's 1989 performance in which she explores the theme of abortion in the streets of Korea and Japan—a work that reflects on the oppression and fraught political situation of the time. In Lim's installation, the artist presents a new work in which she brings two tractor trailers, escorted by helicopters, to the biennale square—a significant place where the exhibition also begins. The trailers contain remains of victims who were massacred because of their suspected ties to communism during the Korean War.

The families of those killed also participated in the performance, along with a procession of the mothers of those who died in the Gwangju Uprising, made offerings among the relics. This very public viewing of the remains (which are yet to be resolved by the government) was perceived as being particularly aggressive in addressing the historical past in the present day. While these two jarring works both challenge the status quo in their broaching of history and confrontation of politics that remain volatile, Lim's aggressive performance in particular—whether it was intended by the artist or not—provides a two-sided question regarding making political artwork involving the artist's deliberate choreography. As such, the works are profoundly topical because they confront the oppression of the body and contemporary controversy around human rights, pointing not only to the history of Gwangju but as an ongoing issue both in Korea and around the world.

This emphasis on fraught global politics is paralleled in work such as that of Turkish artist Gülsün Karamustafa whose Prison Paintings (1972-78) depict her own experience of imprisonment for political activism along with the individual stories of others imprisoned with her; other works include Lost and Found by the Pakistani artist Huma Mulji that depicts a life-sized human figure made of animal hide lying debilitated and distorted on the ground referring to those who 'disappeared' in Pakistan; the works of South African artist Jane Alexander who created a site-specific large-scale installation of new and existing works focusing on the issues of power structures and state control; and the brightly-lit carnivalesque sculptural installation made from everyday objects and life-sized figures called The Ozymandias Parade (1985) by American artists Edward Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, who palpably question military and state authority.

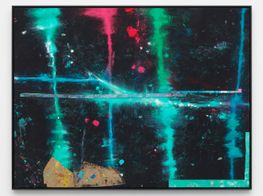

The theme of burning and fire as a conceptual and material transformation is prevalent throughout the exhibition, as is the idea of home as defined by its architectural and surrounding landscape. Some works in the exhibition reference the fire quite directly. Liu Chuang's video work follows him around the remnants of the Chinese New Year celebrations in Beijing. Chuang picks up a piece of paper, lights it and walks with it until it burns out. This process is repeated although each casual passerby appears oblivious to his actions. Eduardo Basualdo literally presents a scaled-down house in his work Island (2009), which is constructed from the burnt remains of a building in a historical neighbourhood of San Telmo, Buenos Aires.

Los Angeles based Sterling Ruby presents a series of stoves, one of which was actually used to burn wood in the outdoor biennale square. They are inspired by his childhood years on a rural Pennsylvanian farm. The actual burning of wood directly engages with the key theme of the biennale, namely destruction, material and symbolic transformation.

Transformation is also rendered in the biennale as a curatorial tool. This approach results in a few new commissioned works which may have less appeal as distinct artworks and appear to have more relevance with the biennale theme, but the artworks play a role in bringing the diversity of works together throughout five galleries where the biennale is presented. There is the contribution of Joakim, a well-known French musician, producer and DJ whose three versions of the song, Burning Down the House, which are broken down and mixed with varying degrees of abstraction. The tracks are played at the entrance of the biennale halls, on the bridge between galleries 2 and 3, and at the exit. The walls of the biennale halls are also covered with graphic wallpaper by the London-based design duo, El Ultimo Grito.

The highly processed imagery appears as hazy images of smoke from afar and an array of dots that recall Lichtenstein's Ben-Day dots. Works are installed atop of this vinyl-printed wallpaper, which not only sets a distinct atmosphere for the exhibition but also makes use of an everyday decorating technique to draw attention to what is normally a standard and neutral white wall. In the third hall is an installation by the Swiss artist Urs Fischer that recreates his New York apartment on a 1:1 scale. The interior walls replicates every object in the house, printed on photo-realist wallpaper, and the eight rooms (of the artist's apartment) are used to display works by eight artists: Pierre Huyghe, Prem Sahib, Apostolos Georgiou, George Condo, Stewart Uoo, Heman Chong, Carol Christian Poell and Tomoko Yoneda.

Gwangju Biennale ultimately explores aspects of how the institution can memorialise the uprising. Burning Down the House continues in this spirit, animating the concept through political engagement and symbolic and physical artworks. It follows the city's own cycle of obliteration and renewal, thereby engaging its history as well as that of the art world itself which similarly is in a constant state of renewal. Of course there is always a limit as to how much a biennale can re-invent itself each time. Overall, the 10th edition is a continued attempt to connect its location with larger global themes; in so doing one of the questions it raises is not only how the other might see the self, but also how the self can stage itself for the other, a theme exemplified in Lim's performance.

The finale of the biennale, presents French artist Dominique Gonzalez-Forester's M.2062 (Fitzcarraldo) (2014) in a holographic projection of the artist performing as Fitzcarraldo, the subject of Werner Herzog's film of the same name. The familiar indomitable character of Fitzcarraldo who was driven to create the impossible, along with Gonzalez-Forester's ghost-like appearance and fading impersonation of Klaus Kinsky is a reminder that — just like when burning down your house—sometimes you have to destroy a part of yourself to become something else. —[O]