Stephanie Rosenthal

Image: Stephanie Rosenthal, Mortuary Station. Photo: Daniel Boud.

Image: Stephanie Rosenthal, Mortuary Station. Photo: Daniel Boud.

Stephanie Rosenthal is the artistic director for the 20th Biennial of Sydney, which will open on 18 March and run until 5 June 2016. Rosenthal is also the chief curator of the Hayward Gallery in London's Southbank Centre, a role she has held since 2007.

She has a PhD in the History of Art from the University of Cologne, and was curator for modern and contemporary art at Munich's Haus der Kunst. There she curated exhibitions that included monographic shows of Allan Kaprow, Aernout Mik and Paul McCarthy, and also exhibitions such as Black Paintings: Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko (2006).

At the Hayward, as well as shows dedicated to artists such as Robin Rhode, Pipilotti Rist and Ana Mendieta, she has also organised a group exhibition on contemporary Chinese art; co-curated the experiential Walking in my Mind (2009) which engaged with the notion of installation art as experience of personal aesthetic narrative; as well as MIRRORCITY (2014), an exploration of fiction and narrative in the work of 23 artists working in London.

Here she discusses the ideas of her biennial, The Future is Already Here – It's Just Not Evenly Distributed. The interview was conducted in two parts: the first in London last year prior to her departure for Sydney and the second shortly before installation commenced in February.

SSSo, this is your first biennial?

SRYes, this is my first. Can you believe it? [laughs]

SSBefore we talk about the Sydney Biennale, I'd like to ask you about your PhD. What was it on?

SRIt was about black paintings in New York in the fifties and sixties: Ad Reinhardt and Robert Rauschenberg. It was about black being a space for transformation, so the idea of rites of passage. It started with Malevich and Whistler, and then used these painters as a kind of comparison to explain how black can be a rite de marge having regard to the ideas of the ethnographer, Arnold van Gennep.

SSRite de marge?

SRRites of passage have three steps: rite de séparation, rite de marge, and_rite d'agrégation_ ... so you distance yourself from something, then there is an in-between phase, and then you come close to something else. So I'm saying these black paintings are like these in-between phases where you are finding your own language.

SSHas your PhD informed any of your work?

SRYes, I think very much. It's interesting, I think this biennial [the Biennale of Sydney] is a lot about the in-between space ... the crack between the physical and the digital. So, we experience the physicality of our body but at the same time being present in the digital realm. I talk a lot about the 'in-between'. I was just talking about rite de marge, and the fact of the in-between is actually exactly the same. I'm very much interested in that place where you don't know where you are going. So that kind of space where things overlap or fold over onto each other. A bit in the space of not knowing the next step ... because I believe then you already know quite a lot intuitively but your brain hasn't processed it.

SSNow tell us about your proposal for the Biennale of Sydney?

SRThe biennale is called The Future is Already Here - It's Just Not Evenly Distributed; the title references a William Gibson quote. But it's more an umbrella for a lot of sub-themes because I didn't feel I would be able to make this one statement about the 'now'. So I wanted a broad idea and sub-themes that are relevant.

I developed the sub-themes by going to visit artists all over the world and suddenly realising that I met a lot of people who are talking about things that are disappearing or transforming through disappearance. Also, there are many who are talking about science fiction again. You could say that I kind of felt these clusters ... which I think is quite a typical thing. There is a wave of artists who are getting involved in things that also match with my own interests. So I have these seven sub-themes, and I call them 'embassies of thoughts'.

Each embassy has its own name. For example, there is an 'Embassy of Disappearance' or 'Embassy of the Real', which embrace that kind of questioning or renegotiating of fiction. Then there is an 'Embassy of Translation'; it's a term I use instead of re-enactment or reiteration, related to the idea of redoing. Artists look at historical subjects of other artists and translate them into the twenty-first century. There is an 'Embassy of Spirit', where artists deal with, say, fundamentalism or religious rights, but at the same time it is about kinds of rituals that would be rooted in personal experience rather than a global understanding of religion.

Each embassy has its own venue and the place reflects the idea of that embassy. So, for example, the 'Embassy of the Real', which questions how we perceive reality nowadays, is a venue which is 20 minutes away by boat. It's on an island called Cockatoo Island, and it has historical value because there were convicts held there.

Now there is also an industrial part that is a naval shipyard. Submarines were built there and later ... I think, steamers or quite grand boats. So there are these massive turbine halls like Tate Modern, but not refurbished, so it's a real industrial building. The interesting thing for me in relation to the 'Embassy of the Real' is that on the one hand it has historical value and it's a kind of museum, so there are these museum panels that explain things (for example, turbine hall, electrical shop). On the other hand, they rent it out as a set for television or movies.

The interesting bit is that it's not treated as you think, it's more like things are added ... For example, if Angelina Jolie shot a bit of her last film there, and, say, built part of a nineteenth century building, then someone else thinks it's quite handy to keep it because it's quite attractive ... Then another director might think, 'This building is really great so let's paint it green for our movie.' And it then gets painted back. So you get here and something looks wrong.

I realised that there is a building that looks like it should be from the nineteenth century but isn't, there's a brick wall, but it's not real, it's just wallpaper. Then you get these museum panels. So this question of what's real becomes questionable, and it's exactly what I want to have for this kind of art. So you begin to question when things that are fake can actually seem more real. So there is this slippage ... For each venue we tried hard to find something right for the artist's thinking.

SSWhy did you use the word 'embassy'?

SRI like this idea that an embassy is a safe place for someone who is basically not belonging, who comes from a different country. Say, the 'Embassy of Thought', I like the idea that it is a safe place for thinking. Also it is related to the idea that nowadays we are united not by nation but where our passion, our desires or our beliefs lie. I wanted to bring in the question of who is owning a space, and how we own space and how we are united. Because I think in every country—for example, Australia had had all these problems with immigration and how it's dealt with—I wanted to address that issue without myself saying what's right or wrong, but more saying that art can create these safe places, like islands, where you can act within your own laws.

SSAnd you also have 'attachés', what do they do?

SRWell the attachés are all people I like and appreciate, so I feel that we can think together. The idea was that doing a biennale doesn't really allow you to go as deep as one wants ... I feel like I'm going back to school and I've been in my business some 20 years. I thought, 'How do you work with 80 artists?' I've never worked with 80 artists at one time before. So I really wanted to have a support structure to how I can make sure a conversation with an artist can have a certain kind of intensity instead of let's talk once on the phone and I'll see you again in six months.

The rule of the attaché is to work with some of the artists and decide on the commission. For example, Mami Kataoka [chief curator of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo] and artist, Taro Shinoda. I can say to Mami, 'Taro is doing this, would you mind if ... " So curating makes sense because that conversation is happening, and I believe that if conversation is not happening a lot today, then what's the reason for having a curator?

Because, why does an artist need a curator? My hope is that the attachés would add a certain depth through their own expertise. I would work with some of them in relation to an embassy—say if they've written a book about it. In a way the [having the] attachés is also so I don't have to quickly become an instant expert on a topic or place.

SSWhat about the artists? Tell us how some of the artists fit your embassies?

SRLet's start with the 'Embassy of Disappearance'. There are 20 artists in that embassy, one of your Singaporean peers is Charles Lim. Another Singaporean, Robert Zhao Renhui, is doing something about an animal that doesn't exist any longer on Christmas Island. This island was owned by Singapore but now belongs to Australia. It also examines how land is changing ownership and what gets lost in that change. There's also a Japanese artist called Yuta Nakamura who works with different bits of ceramics he finds all over Japan. He creates this postcard where he tells the story of that ceramic and the history of how it came to be broken.

That kind of work is related to the idea of memory and disappearance. It can also be the sun that is disappearing. Neha Choksi, an Indian artist, is making 50 different images of sunsets and she layers them over each other so a performer rips each poster off and at the end there are all these sunsets blurring into each other. There is Maria Isabel Rueda, a Colombian artist who documented the house of another famous Colombian surrealist painter, Norman Mejía. Normal Mejía did all these sexual surreal paintings and lived in a castle by the beach.

So people considered that he was using witchcraft. He eventually had to leave that house because he was threatened all the time. But he painted that house on the inside, so her work goes back and shows how he had disappeared from people's memory. There is also a group of artists in the process of doing a show in Fukushima, which is obviously invisible because it is in an exclusion zone. It is a work where the audio embodies that idea.

For the 'Embassy of the Real', Maaike Schoorel is in that. I am interested in developing the theme out of contrary things. There is the physical experience of the body—the performative or dance that I've always been interested in. The other one is artists who work digitally or on the internet, just to make that point that we live in this overlap, where you constantly meet each other on a physical but at the same time on a digital level. I feel that we're in a time where we accept that both are relevant now. I think five years ago there was still this anxiety that we're losing our bodies and no one is aware.

Now I think artists realise that we live on the phone, but being embodied (like having sex) is still important. So the question of this embassy is what does this do to our perception? The key piece here is Malevich's Victory over the Sun. I invited an artist to recreate that 1913 opera. I still want to explore how Malevich's black square is already talking about what the internet or cyberspace is—that fourth dimension. I'm intrigued to see in this opera where he developed the black square, that maybe everything is already there when we talk today of this kind of extension into an unlimited space like cyberspace.

Another artist is William Forsythe, who will make a new installation where you experience the gravity of your body, but also will create a kind of anxiety because it is a huge tube which is pushing you down. You will have to crawl under it, and you'll really feel your body in that you might not fit in comfortably ... Then there is Camille Henrot and also Cécile B. Evans.

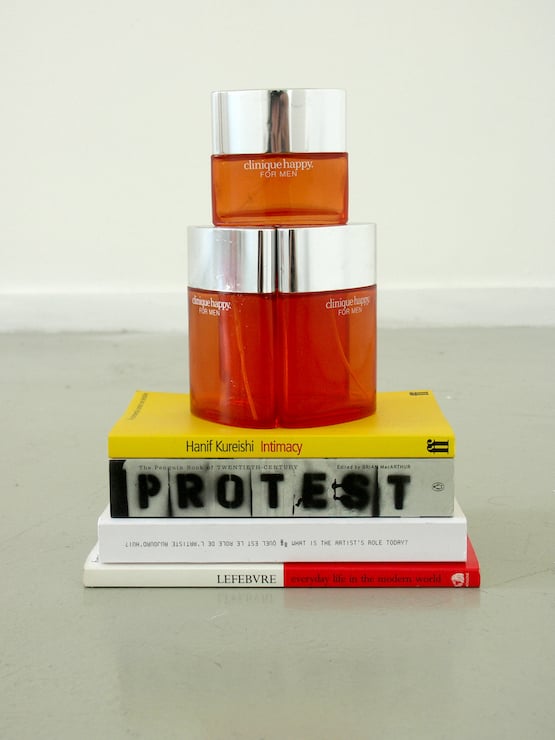

We are using a little bookshop in the Redfern area. There, Heman Chong has decided to do an 'Embassy of Stanisław Lem'. It's a very simple work, he asked the bookshop to only sell Stanisław Lem books in Polish and English. He wrote a little story that goes with each book. This is partly to suggest that the English translations are not great ... though I don't know how he knows. But what I like is that it is also something that is transformed from one thing to something else. So this 'Embassy of Stanisław Lem' on a quite literal level has a direct connection to the 'Embassy of Translation'.

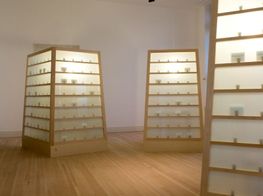

It is literally about how in the act of translation something gets lost, and in the 'Embassy of Translation' we deal with this in an abstract way. How can we recontextualise something nowadays and artists are interested in this. It will be in a mortuary station. It's a place where coffins were transported from the city to the cemetery. Today the station is in the centre of the city and it's not used any more. It's a beautiful building so it's a great venue.

There will be things happening across the city, hopefully we'll be able to realise a work which will outlive the biennale time of three months and it'll be a trace left in the city. Agatha Gothe-Snape will work with different performers and choreographers and explore different parts of Sydney to create a language and this will then be implemented either on the buildings or street. Hopefully this will create a kind of memory. I imagine there is a kind of spontaneous popping up of an event, instead of leaving large sculptural works that clutter a city ... [smiles]

SSI see that it is a massive show, there are some 15 or so venues. What is it like to curate 84 people into 15 venues?

SRFor me that's the joy of it. It's not in one place, so you have all these different aspects of it. It is a little bit stressful. I am enjoying not working within one institution. It's also very dynamic, in that sense it's earlier, because I can't do the nitty gritty things. I really have to keep conversations with the artists, we discuss the concept then someone else takes over. Working on such a big scale, a lot of the things I usually do I have delegated like sourcing of materials and all these tiny details. I really just like doing the content. I only really get involved if, say for example, something doesn't work with the venue. I'm getting a massive amount of emails, I read them, but only get involved if I have to.

SSDo you have a lot of people working with you?

SRIt is an extremely efficient team. The Biennale of Sydney is very well organised. Not all of them have done many exhibitions but they have done many festivals and big productions. Cockatoo Island is a massive industrial building, not necessarily ready for artworks, so the team had to deal with other things as well. All the places in the city, it was quite nice to have the opportunity to explore with works.

So it's quite nice, instead of having to go to an office and having meetings, basically here it's much more working and meeting from wherever I want to work. It's much more of a freelance curator's experience. It is very different from working in an institution. Here I am just dealing with the vision, there is less to do with fundraising and things like that to worry about.

SSI'd like to ask you again about the performative. I notice that there are a lot of object makers, but I wondered if there was a more performative component given your background?

SRIt's not as much as I had hoped. For instance, with my performance and dance background, I was really interested in integrating a public programme more into the biennale. But in fact it is a very straight forward public programme. In the end there was not enough time ... However, there is a very performative aspect at the beginning, but it's not as many works as I hoped, so what I did instead was to arrange more things in the first week, performances in the day or the evening. And then you have works that are performative in the sense that they change and transform.

Or the performance is happening in the sense that the works change over three months. Finally, there are fewer pieces where the visitor becomes the performer, which I'm usually very interested in ... it's just the one piece by William Forsythe, Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time (2015), which is a beautiful one with the pendulums, where people can go in and dance with the candles.

SSAnd some things will change over the period of the biennial?

SRYes. For example there is a work by Neha Choksi, and it's a work where she programs/photographs the sunset in different places several times and then she presents the digitally composed or painted sunset all on a huge wall. Basically they are wallpapered over each other, then over the run of the show they get torn off, so each week the work looks different. Lee Mingwei's Guernica in Sand in which he's recreating [Picasso's] Guernica in different coloured sand and then he's brushing it off. It becomes an abstract painting.

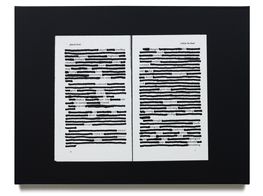

Germaine Kruip who does a performance, A Square, Spoken. It involves a one to one conversation: you book in and then a performer will tell you all the different quotes about the black square. It is a performance based on the collection of the museum. I think it's an interesting one. We also spoke about Justin Williams and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, who are doing a recreation of Malevich's Victory over the Sun. The score is actually by an English composer, Huw Belling, and Pierce Wilcox wrote the libretto.

SSSo to sum up?

SRI also think a biennial serves to introduce people to contemporary art who haven't been engaged before. Why I was excited to do it is that it allows me to show works beyond public institutions. This biennial has a long tradition of being in public institutions, so I am trying very much to get away from that as much as possible. I think it's different going to a museum to see a biennale than falling over it in the streets. So we're really trying to extend it quite a lot in different areas, well, actually to try to have a balance.

Because the Sydney Biennale is free, you can just walk down the street as a 13 year-old and see something and think, 'Wow! This is nice and I want see more!' But I also feel that you need to connect to the people who live in the city of the biennale. To invite artists from Australia is just a way to create a connection with those people who live there, and at the end of the day these are the people who we want to come and see it. There is a bunch of people who will come to the opening and maybe just after, but at the end it is really for the audience there. I enjoy the thought that this is possible—to connect with the people in the city—for me, that's a big purpose for biennales still.

SSThe aim is to get a different kind of audience?

SRYes, the people who travel to museums are already a certain kind. I like the thought that with a biennale you look slightly differently. That art can make you look at the place differently. And you get someone who has ten minutes and stumbles into a work in a bookshop—and there you have a different approach. —[O]