Peter Halley's 'Conduits' Abstract Reality at Mudam

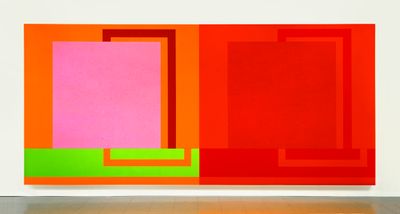

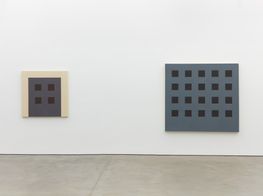

Peter Halley, Asynchronous Terminal (1989). Acrylic, fluorescent acrylic, Flashe, and Roll-a-Tex on canvas. 248.92 x 243.84 cm. Exhibition view: Conduits: Paintings from the 1980s, Mudam Luxembourg (31 March–15 October 2023). © Photo: Mareike Tocha/Mudam Luxembourg.

Rarely does a modernist painting exhibition of historical significance organised today resonate as powerfully as Peter Halley's Conduits: Paintings from the 1980s at Mudam Luxembourg (31 March–15 October 2023), curated by Michelle Cotton assisted by Sarah Beaumont.

The key to the relevance of this show is apparent in Halley's interview with critic Henri-François Debailleux, which describes the dialectics between the real and abstract that shape the artist's thinking and paintings, and, more specifically, his pursuit of being a realist in an increasingly abstract society.1

The exhibition opens with the muted colours of a large acrylic on canvas, The Grave. Painted in 1980, it depicts a dark grey landscape against a brown sky with a vertical light grey rectangle in the middle.

As Halley told writer and curator Trevor Fairbrother, aside from referencing the passing of his grandmother, the painting marks a response to his return to New York in 1980, where he experienced alienation and isolation amid the dizzying effervescence of the city's urban landscape, which would influence his entire career.2

In this sense, the 1980s marked, by Halley's own admission, the beginning of his journey towards working through personal loss while navigating and representing a new sense of enclosure.3–

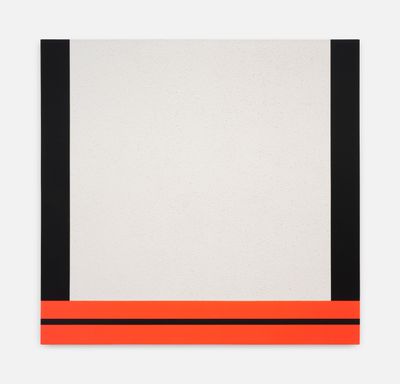

He began to create paintings whose hard-edge textural compositions recall electronic circuit boards and digital pixels of computer-generated, low-resolution imagery. Increasingly, his paintings became more colourful as he started painting with Day-Glo materials, which he describes as a method to intensify colours beyond their usual, common, and natural expression.

A Monstrous Paradox (1989) shows a double panel with the same composition painted twice. On the left is a circuit composed of a pink square against a fluorescent orange ground. It meets a green Day-Glo panel below, lined with an orange border at the bottom edge.

A red conduit emerges from the top of the square, turning 90 degrees down the orange backdrop to connect to the green base, where an orange line parallels the horizontal divide between the two.

...these visual codes create associations that fit into and construct a self-contained world with its own logic.

On the right panel, the composition is reproduced in shades of red with its central cells filled with Roll-A-Tex, a textured additive commonly used to smooth out imperfections in cheap houses. Like a metamorphosis of the same pattern, the latter panel acts as the former's virtual afterimage.

Despite being abstract, the repetition of visual elements across Halley's paintings—like cells, which appear as monochromatic squares or rectangular smokestacks—operate as concrete units of meaning. Functioning like words, these visual codes create associations that fit into and construct a self-contained world with its own logic.

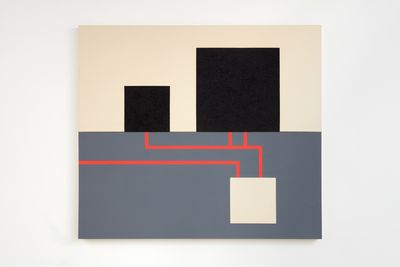

Take Cell with Smokestack and Underground Conduit (1985), which depicts a large yellow cell with a chimney painted against a black landscape. The canvas meets a grey panel beneath where a red line—a conduit—moves from the right side of the canvas up to the bottom of the yellow square.

The black lines Halley calls 'conduits' function as the connective tissue of every composition, dividing or cutting through the image plane. They also mark the distance between cells, which stand for dwelling or other social units.

Prisons are represented as cells that contain vertical bars to look like cell windows. These augmented squares subvert the supposed neutrality of minimalist geometric abstraction by transforming their characteristic neutral shape into a representation of confined spaces.

In Prison with Conduit (1981), a prison cell is positioned in the middle of a white, Roll-A-Text-textured background, as a fluorescent acrylic red strip forms an underground chamber containing two black conduits below.

Underground chambers are a crucial visual element that emerges in 1983 paintings like Two Cells with Conduit and Underground Chamber, which consists of monochromatic squares and rectangles on the lower panel.

According to Halley, this deployment of the underground chamber represents the prominent role of models in infrastructure construction within the larger world, to which his paintings refer.4 Reversing the complexifying trajectory of capitalist aesthetics in a decade marked by the rise of cable television, MTV, video games, and other visual technologies, the simple elements of Halley's visual vocabulary gradually become diagrammatic.

But the diagrammatic significance of his paintings emerges gradually for Halley, while making deep observations of his work through his own writing. This led to the artist's conviction that the evolution of abstract art parallels that of the social sphere. Abstract art, he writes, tells 'the history of the organisation of the compartmentalised spaces and the formal systems that make up the abstract world'.5

Halley sees his practice as arriving at a moment of awareness of the crisis of geometry and its formalist project.

Thus, his painted diagrams not only function as concrete abstractions of reality. They can be interpreted as forms of digital realism, albeit in low resolution, utilised to grasp the concepts and components shaping social conditions in the information age.

Halley sees his practice as arriving at a moment of awareness of the crisis of geometry and its formalist project. Neither interested in critiquing particular forms nor longing for a past where geometry contained a certain radicality, his paintings contrast but stand in direct dialogue with Frank Stella's minimalist works and Richard Serra's monumental sculptures.

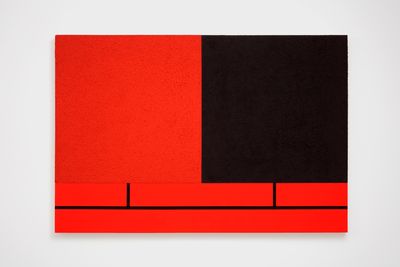

Take Cell with Smokestack (1987), composed of a black landscape and cell with a chimney on a bright orange ground. Here, squares and rectangular cells are the building blocks of post-industrial society.

For Halley, what is at stake is not the mesmerising impact of geometry. While holding a position within the tradition of geometric abstraction, his paintings represent a unique endeavour. They link the cybernetic foundations of the information age's political order with its structuring of forms of economic abstraction, facilitated by the increasing flow of informational signals that shape the social and cultural landscape.

In this sense, Halley's diagrams are not only abstractions of reality in dialogue with the long-lasting question of abstraction in art history but also the outcome of a procedure that lays bare abstraction's unconscious reproduction, whether through the practice of painting or the process of cybernetic world-making.

Though in Halley's work, these insights are never confined to mere commentary. By doubling down on the ubiquity of geometrical signs, Halley confronts the increasing 'geometrification' of society in its content, structure, and outer form. He refuses to tackle any kernel of being—including intuition and experience—as untouched by the rapid transformation of social order. Nor does he resort to mediums such as oil painting that might re-enchant our current world.

Among works in the artist's Mudam exhibition is a series of Kodalith prints, which feature short-form text reminiscent of Twitter, but made almost two decades before the digital platform's foundation.

Measuring 64 by 75 centimetres, each frame features a Kodalith film surface with isolated fragments of language—such as 'One world or none'—that are taken from advertisements and media, cut out, and placed on top of white matt boards.

Two features of this series are striking. First, the reflective surface of the Kodaliths resembles the black mirror of a turned-off screen. Second, the placement of the letters in front of white boards lends some engraving-like depth to the texts. As a result, visitors can see their reflections etched within the phrase of each piece.

Driving. Voting. Raising a Family. (1988)—the only Kodalith featuring a cell with a chimney—bridges Halley's Kodaliths with the language deployed across his circuit paintings. While Way Out/No Exit, a print diptych from 1988, signals 'Way Out' against a black ground, suggesting the possibility of exiting to be illusory.

That hypothesis of 'no exit' recalls Mark Fisher's capitalist realism, a concept diagnosing the lack of alternative models to neoliberal capitalism, and circles back to Halley's conduit paintings, which effectively describe closed circuits.

Halley's only video work in the Mudam exhibition is Exploding Cell (1983). The animation showcases the construction, connection, and transmission process of the cells usually deployed in his work. Except in the case of this time-based work, the rising smoke from the cell culminates in the explosion of the entire closed system.

To contextualise Halley's understanding of the social history of computers within our ongoing technological revolution, I asked him during the Mudam exhibition's press tour about his feelings regarding the emergence of AIs like Chat GPT and the effects they have on our social structures and the language we speak.

While looking around at guests with a sense of despair, he said: 'I think humans are inevitably on their way to becoming electromagnetic signals themselves.' —[O]