Guadalupe Maravilla Connects Healing Practices from East to West

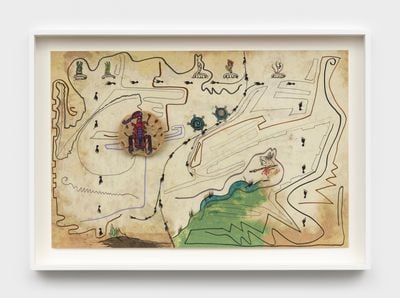

Guadalupe Maravilla. Courtesy the artist and P·P·O·W, New York. Photo: Steve Benisty.

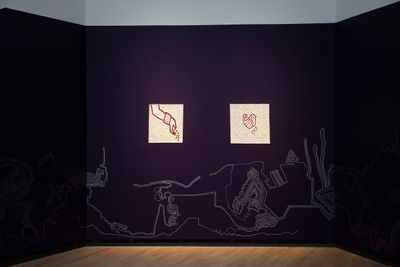

Guadalupe Maravilla. Courtesy the artist and P·P·O·W, New York. Photo: Steve Benisty.

Guadalupe Maravilla's practice and resulting artworks centre mostly on healing as an individual and societal tool to overcome trauma, drawing from his background as a child of war and experiences as a cancer survivor to build spaces focused on communal care and healing across generations.

At the age of eight in 1984, Maravilla fled civil war in El Salvador and arrived in the U.S. undocumented. As an adult, he overcame colon cancer, which led him to learn about global healing practices from cultures as far-reaching as Mayan and Tibetan, alongside standard medical treatments like radiation and chemotherapy.

Accordingly, his practice brings together often separate knowledge systems, from Western Cartesianism, which sees the mind and the body as separate entities, to non-Western and non-hierarchical approaches that look to nature and natural remedies for healing and tend to view humans as part of a wider cosmological system of equal parts.

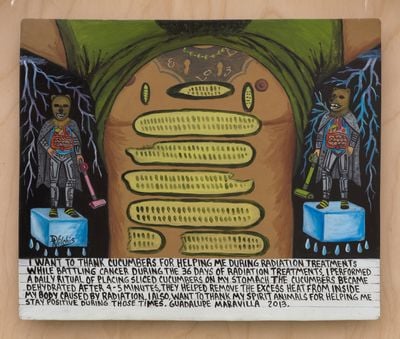

For Maravilla's first exhibition in Europe, and most comprehensive to date, Sound Botánica at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter (18 March–7 August 2022), over 30 works comprising monumental sculptures, drawings, a large-scale mural, and instances of activated sound baths fill the institute, including four major bodies of work: 'Tripa Chuca' (2016–2020), 'Embroideries' (2019), 'Disease Throwers' (2019–ongoing), and 'Retablos' (2021), which are devotional ex-voto, or votive paintings.

Speaking to the ethics of artistic creation, both the retablos and embroideries were made with collaborators specialised in such forms, co-authored, and fairly compensated—all of which are important to Maravilla and his wider way of working.

Sound Botánica unfolds over two main gallery spaces with the most captivating and monumental works on view being Disease Thrower #4, #6, #7, #8, #9 (all 2019)—totem-like sculptures that each incorporate a sound gong, assembled from plaster of Paris made by microwaving tissues and plastic that hold together objects collected during the artist's travels.

The most recent Disease Thrower #13 (2021) is an astounding work measuring over two metres high made from cast aluminium, moulding vegetation and nature into a constellation of organic forms, some related to the healing and nutrition during Maravilla's cancer treatment, with notable vegetable forms like squash placed besides real squash at the base of the sculpture.

In the conversation that follows, Maravilla speaks about forced migration, how trauma manifests in the body and the collective, and disrupting boundaries between art and life, with a practice led by a personal commitment to create a more equal and equitable world.

JDSome of your artworks, such as the series of monumental sculptures 'Disease Throwers', are activated through performative gestures. I notice they are made of materials like luffa sponges, anatomical models, gongs, glass bottles, and the invented plaster you create by melting tissues and plastic in a microwave.

These are hybrid, totem-like sculptures that draw from your experience as a child who migrated undocumented to the U.S. They also bridge Indigenous cultures with ritual, and speak to your cancer treatments, which have included modern medical techniques alongside healing practices.

How did you bring together these intersecting knowledge systems and develop an art practice centred on collective healing experiences, as the exhibition Sound Botánica at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter demonstrates?

GMI am interested in collective healing and the intersections between the Indigenous and the medical, and dismantling systems. My daily experiences are the core of my work. People often wonder how I can be so open about having cancer, being undocumented, and being a child of war.

I escaped the civil war in the south of El Salvador in 1984 and migrated to the United States, which separated me from my family; this is very common with migration. Somehow, I made it to the United States—I feel very blessed to be in this position, as an artist now exhibiting all over the world.

I have a teaching position as a professor and all these great things, so I think of how lucky I am, but I also think back to the kids who did not make it, particularly those who crossed with me. On the other hand, because I'm a cancer survivor too, I can make a direct connection between the trauma of the civil war and seeing violence as a kid and the illness that came to inhabit my body.

My approach to life is very simple, I don't force anything. I go with the flow and when things are difficult, I ask myself, what am I learning?

I believe intersections between conflict and illness exist, and a lot of the work that I do in community spaces centres on survivors, health, and political asylum, paying attention to people who are crossing the border into the United States and the trauma they carry.

These traumas can manifest as serious illnesses and severe mental health issues that are left untreated because people live in survival mode. They don't think about healing the trauma, or they cannot afford therapy and health care. Besides mental health decline, there's also physical health neglect, because people are trying to survive and feed their families.

Back to your question, I connected my experience of war to how my trauma manifested as a cancerous tumour in my gut, which developed into stage-three colon cancer when I was 35. Now I see it as a blessing; I wouldn't be the person I am today without having survived that experience, or making the work I'm making now—I wouldn't be able to help at all.

My approach to life is very simple, I don't force anything. I go with the flow and when things are difficult, I ask myself, what am I learning? What am I supposed to learn? I took this approach when I had cancer and learned from healers all over the world, from Tibet to Korea, China, Israel, and the Americas, as well as Indigenous people from Mexico and Central America—Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Colombia.

I see life as an entire cosmology, so it's important for me to represent connection rather than separation.

I learned about plant medicine, sound healing, and natural healing from medical cancer treatments like radiation, chemotherapy, and surgeries. I learnt all these different ways of healing and confronting deep trauma, and this is what I'm teaching now, which is based on my lived experience.

JDSo for you, healing is a collective act?

GMYes, but everything I do and teach comes from lived experience. I don't believe in healing anyone with a magic wand and I'm not the type of healer that's going to take credit for anyone healing. I believe that everyone is their own medicine and we all have the tools to heal ourselves.

JDWalking through the exhibition, I noticed different symbols and references to medical and traditional objects, including hands, feet, bleeding hearts, recurring across bodies of work, from the 'Disease Throwers' sculptures to the 'Embroideries' series and the Tripa Chuca mural, which references the Salvadorian game you played growing up and during your migration to the U.S.

To me, these speak to a dual position between presence and absence of the body, and inside and outside, whether through anatomical models of organs, or the language of embedded bodies in animism, both human and non-human.

JDWhen illness inhabits the body, the relationship changes and the body, or the Western notion of Cartesian wholeness, in a sense becomes undone. Could you speak about the making and unmaking of this idea of the self from the perspective of a trauma survivor? How does one find alternatives to practices of wellness informed by capitalist incentive, which can also be exploitative?

GMGreat question! The references and symbols in my work vary and present a constellation of meanings. I take the same approach to healing as I do to art-making and think of different ways of connecting migration to health, as I see a direct connection.

For example, in the drawings and embroideries, there's a recurring use of Indigenous hand symbols from Mayan culture. The ice cube held by the hands references I.C.E., which stands for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement, while the found objects come from markets throughout Latin America, as I go back and retrace my migration. Some are also connected to healing practices and rituals from their places of origin.

I see life as an entire cosmology, so it's important for me to represent connection rather than separation. As an artist, I am first a human in the world, so it's crucial to not separate who I am from my art. The way you behave in society and the world is not separate from being an artist, either—you can't be a jerk and make work and expect people to like you.

JDCollaboration is also central to what you do, in the layering of thoughts but also the collective making. Could you speak about a body of work in this exhibition that represents a significant coming together of ideas in the making process?

GMThe collaborators are important and there are many different layers, so different factors and types of collaborators naturally come into the mix. For the 'Tripa Chuca' series, the person I collaborated with was formerly undocumented; she's going through the process of getting her citizenship now.

She was able to travel with me to Oslo and make the drawing with me, which has been a beautiful experience for her, as she hasn't travelled much since she arrived in the United States as a child due to her undocumented status.

JDYou also worked with a fourth-generation retablo painter for I want to thank these magnificent fruits Retablo, I canceled my performance Retablo, and Fire Ball Retablo (all 2021), which are works that incorporate retablos, or devotional ex-voto painting.

GMIn the journeys I've made retracing my migration or looking for objects, I often get into conversations with people and one of these was in a market in Mexico City, where I got talking to someone who made retablo paintings passed down from his family line.

His name is Daniel Vilchis, he's in his 30s—I hired him to make the first painting and now we have a beautiful collaboration where I send him digital sketches and he translates them into paintings. The composition and colours are entirely his and he signs the works.

I'm always looking for different ways to collaborate with people and create this microeconomic model around art practice that shares and distributes resources.

I recently met someone who carves objects out of volcanic rock, in another market on my travels. I am now working with him to respond to my drawings via this volcanic rock medium, which symbolises the volcanic landscape of El Salvador.

JDWhere do you situate ethics within your practice, in the collaborations, and how do you co-create across geographies? During the exhibition tour, you mentioned the preservation of handmade traditions that are passed down from one generation to the next.

I ask because there can be overarching power dynamics within collaborative work, or at times, a lack of clarity around authorship, an erasure of so-called artisans, and so on.

GMEthics are really important to my work and collaborations, which is why they are signed by the makers and credited. This is expressed in my exhibitions, but I'm also terrified of the erasure of skills that have been practiced for generations.

With the pandemic's effect on tourism, David, the fourth-generation retablo painter will have to stop painting eventually. He was someone I kept working with during the lockdowns, who was really active. I also pay fairly and continually think about paying in line with U.S. rates, as opposed to cheapening his labour because he lives in Mexico.

JDHow do you negotiate bringing healing practices from your experiences into an institutional space, considering you work very communally and with communities at the centre?

GMThere are many challenges, but I don't see the work I do as strictly for museums and institutions. I work with many groups of undocumented individuals in various spaces, and a lot with the cancer community. I don't really charge for healing either.

I make money by selling work and teaching so that eventually I can open my own temples that would serve as community centres and healing spaces, especially for marginalised communities.

These spaces are going to be free from the state, governmental forces, the church, and other institutional spaces. I'm building my reputation as an artist with this profile to get there and I have a few years of planning and working towards this goal. —[O]