Pauline J. Yao

Pauline J. Yao joined M+, Hong Kong's operating, but as yet to be housed, museum of visual culture in late 2012. Prior to joining the museum, Yao served as Assistant Curator of Chinese Art at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco and holds an M.A. in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago.

In 2006, Yao travelled to China on a Fulbright grant and subsequently co-founded Arrow Factory in Beijing, one of the city's important alternative art spaces. In 2007, she was the inaugural recipient of the Chinese Contemporary Art Award's Art Critic Award. She is the author of In Production Mode: Contemporary Art in China (2008), and co-editor of 3 Years: Arrow Factory (2011). And she is a regular contributor to Artforum, e-flux Journal, and Yishu Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art.

Anna Dickie sat down with Yao to discuss her path to M+, starting Arrow Factory, the M+Digital project, building the M+ collection, and what she looks for in an artist.

ADWhat is the earliest artwork you can remember?

PYIt would have to be something I saw at the Art Institute of Chicago. I grew up in Chicago and we went there a lot when I was young. There isn't one particular work as such but I remember the permanent exhibits of medieval armour and Buddhist sculpture.

I think what made me interested in art is that it exposed me to different things. It made me want to learn more and to pursue more about the world.

ADYour first major role in the art world was as an assistant curator at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. While you were working there the exhibition, Inside Out, toured America. I understand you were involved in that?

PYYes. I worked at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco for around six years in the late 1990s to early 2000s.

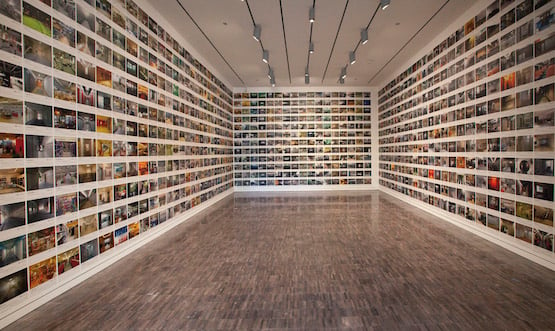

Inside Out was a very influential exhibition of Chinese contemporary art that traveled to America at that time. I was at the Asian Art Museum when the show came to San Francisco, and so was able to be involved in the installation of the show there. It was also one of my early encounters with contemporary Chinese artists. I recall helping Xu Bing set up his work Book from the Sky and seeing seminal works by Big Tail Elephant Group, Cai Guo-Qiang and Gu Wenda in person for the first time. It was a landmark exhibition for contemporary Chinese and Asian art in the United States.

ADIn 2006 you moved to China. What took you there?

PYI received a Fulbright research grant to go to China, and went there in 2006 to research modern and contemporary Chinese art. My area of focus was on the emerging generation of Chinese contemporary art collectors.

ADWhy did you choose to research the collectors?

PYThe reason I chose that topic was because up until about 2005-2006, collectors of Chinese contemporary art were predominantly not Chinese. There were collectors buying contemporary Chinese art, but they were mostly foreigners or people living outside of China travelling to China to buy things or those residing in China on a short-term basis. A shift began to occur around 2005 in which Chinese collectors took increasing interest in contemporary art. With my Fulbright I was interested to look at habits of collecting from a more localised perspective and to understand how Chinese collectors approached contemporary Chinese art.

For various reasons, most of them economical and political, there hasn't been much of a culture or habit of collecting contemporary art in China until very recently. But around the mid 2000s there were a few Chinese collectors who were starting to take an interest and they were beginning to buy contemporary art, and to get to know artists and go to shows and follow things. I was interested in researching this transition and upswing of activity. What made these new Chinese collectors interested in contemporary art? How were they approaching the idea of building collections?

ADTo what extent do you think individual collectors have influenced what is considered 'Chinese contemporary art' today?

PYCollectors have played an incredibly important role. Early on, many people outside China came into contact with 'Chinese contemporary art' through the eyes of foreign curators and collectors. The Ullens Collection and Uli Sigg Collection are but two examples. As time went on, the picture became more diverse but contemporary art in China—largely because of the lack of state support—has always been heavily reliant upon private resources and commercial art channels and therefore collectors are at the centre of this.

The shift in collecting towards the home turf can be witnessed in the growth of private museums being built in China, some of them by prominent private Chinese collectors. These museums do not solely display their own collections and also frequently host and organise other exhibitions. But it's still very hard to find any kind of regular or fixed display of contemporary art from China covering a vast period of time that could act as a type of historical overview or permanent collection equivalent to what we see in western museums.

To date there is virtually no museum where one could encounter the breadth and history of contemporary Chinese art over the past thirty (let alone fifty) years in the same way as one may find in other museums such as the Tate Modern collection, or MoMA. In China, one can only find very limited views. The National Art Museum of China (NAMOC) has occasionally presented grand surveys, but these are still usually an official story that doesn't stretch into the present. In terms of collecting, the historical narrative somehow comes to a stop in the 1980s with more recent examples being of the highly conservative variety.

It is so important to have a museum that can narrate the more recent histories of what has been happening in terms of not just contemporary Chinese art but of the development of contemporary visual practices in Asia as a whole.

ADM+ has taken on that mantle of being such a museum for Asia. But let's talk first about the non-profit that you founded in China, Arrow Factory, and then M+. How did Arrow Factory start?

PYArrow Factory came about as a result of a confluence of factors occurring at the time. It was Beijing's pre-Olympic moment, and the art market, as well as the whole national economy, was in full swing. There was a lot of energy and a lot of capital flowing into Chinese contemporary art: 798 in Beijing was blossoming, with new art spaces opening, and several new overseas galleries setting up shop. The period was filled with aspirations about growth and expansion and desires for everything to be bigger and better.

Against this background, myself and a couple of artist friends of mine started talking about the possibility of doing something small, something that would go totally in a different direction. It was already clear that artists were being pushed to produce their work in big and more spectacular ways. Making big artworks can be easy if one wants to throw money at something. But it can actually be much harder to work small. We started talking about abandoning the reliance upon scale and powerful visual effects and going for something understated and tiny. So we came up with the idea to do shows in a small place and to do something that would push artists to work in a really small or intimate way.

Along with this was the desire to work outside the confines of the art district. It became important for us to find a space that was embedded in the urban fabric of the city, and immersed in a neighbourhood, away from the manufactured district that 798 started to feel like—it was overpopulated with galleries, museums, and cafes.

Above all, we wanted Arrow Factory to be a location where people who weren't really planning to see a show, or were not really thinking about art, would suddenly come across something by accident. We ended up finding a modestly sized storefront space inside a small alleyway that was sandwiched between fruit sellers and noodlemakers in a residential neighbourhood. A two-year lease was signed and we began to do projects there in Spring 2008. It's now been seven years. Hard to believe! When we started I don't think any of us thought it was going to last beyond a year or two.

ADYou are now a curator at M+, what do you think your experience with Arrow Factory brings to your role with the museum?

PYI think most people see what I did with Arrow Factory, a tiny 'alternative art space' and what I am doing now with M+, a massive government-funded institution, as being totally and utterly different. Certainly, going from a super small, artist-run, low budget, non-profit, non-commercial, spontaneous kind of thing to a mega-institution with highly professional operations comes with some adjustments but the difference is not as radical as it might appear.

Lars [Nittve] has a phrase he often repeats which is that "a museum is not the same as the building". It means simply that a museum is more than a building, it is fundamentally about facilitating encounters between art and a public. In this sense, M+ and Arrow Factory are actually not so far apart. With Arrow Factory we were also trying to facilitate interactions between art and the immediate surroundings or local residents, and the location we chose allowed us to reach what we felt was a more diverse public in a more direct, unmediated way. The experience we hoped for was one that wasn't framed by an art district, or knowledge about the art world, and didn't require the necessity of having to go into a museum or gallery space. We were trying to create unique and unexpected encounters for the everyday average person, not those already educated or specifically interested in art.

Of course at M+ the scale is bigger and what we do involves much more curatorial research and planning—not to mention bureaucracy!—but at the core we are a public institution there to serve a public and in this regard we have to think about interpretation, and accessibility. In both instances—with M+ and with Arrow Factory—the task of working with artists is not contained in lofty intellectual debates but also in thinking about how the work interacts with its space, what lies outside the space and how these things can be made relevant to a multitude of audiences.

ADTell me about the M+ art collection and how it is progressing?

PYThe collection continues to evolve and develop in myriad directions. In terms of visual art, we are building on the strengths of the Uli Sigg collection, and we're developing the collection further in terms of Japan, Korea, Taiwan, South East Asia and beyond.

M+ is a museum that has this mantle of being a museum for Asia, but it is also a museum for Hong Kong. I think it's incredibly important for us not just to collect the work of Hong Kong artists but to work on understanding how Hong Kong sits within the bigger context of Asia.

My work on the collection spans from China, Taiwan, Japan, to Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines and as well to Europe and America. In terms of timeframe, it reaches from the 1960s to the present. Increasingly, I am working with so-called Asian diaspora artists—those artists born and raised in Asia who settled elsewhere or Asian artists who reside overseas. So yes, it's a pretty big area to cover but of course I am not the only one working on this. Since the curatorial areas at M+ are not territorially or periodically defined, we have a lot of overlaps and I move freely between artists of different generations and regional backgrounds depending on what is needed.

ADIn terms of your role at M+, I understand you are very involved with M+Digital. Can you please tell me about this project?

PYSure. M+Digital is an ambitious multi-layered, curatorially driven online platform that will serve as an arena in which to experiment with and implement new digital strategies for the future physical museum.

M+Digital is comprised of several key building blocks, one of which is an online journal that will be released three times per year and headed by an editorial team based primarily in Hong Kong. The journal will cover critical writing on visual art, design, architecture, and the moving image. Its aim is to be semi-academic, and for the more advanced or specialised reader. We will be including commissioned texts, reprints and some shorter-form essays and all of the content will be bilingual in Chinese and English. Doryun [Chong] and I will be the editors for the first two years.

ADThe proposed M+ e-journal very much relates to a passion of yours: critical writing. In 2008, you wrote a paper for the Asia Art Archive in which you questioned the status of critical thinking and writing in China, and in Asia generally. How much has changed since you wrote that paper?

PYPeople seem to remember this article more frequently than I ever imagined! Maybe because it was hard-hitting, but at the same time, I think those things needed to be said. Many things have changed in China since I wrote that: new publications and journals exist now and overall the standards have increased dramatically. However, the language divide in the field of contemporary Chinese art is still very pronounced. This means there are often separate conversations going on in different languages and not so much communication across the English-speaking and Chinese-speaking art worlds.

Naturally, like throughout the rest of the world, the published word holds less weight than it used to. Online platforms and social media dominate the landscape and the way people get new information is not from print publications so everyone is adapting. The unfortunate result is more emphasis on short-form writing and news reporting rather than encouraging longer, in-depth discussions.

ADThe CCAA Art Critic Award you received in 2007 ultimately resulted in the book,In Production Mode. Tell me about this book?

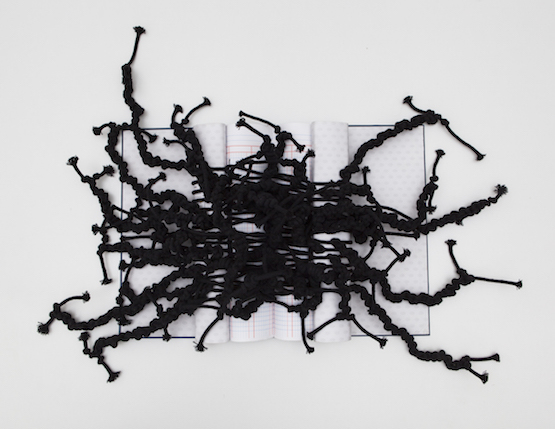

PYThe book was an attempt to unpack the current environment and landscape of art making in China. I was looking at methods of production—mostly artists who were working in studios with assistants to help them realise their work—and how these methods intersected with questions of labour and authorship. We are familiar with artists working with assistants but I felt the situation in China was slightly different because the assistants being hired were frequently manual workers who had no connection to the artworld whatsoever and whose involvement was intrinsically tied to the economics of wage labour. I was interested in investigating the ways in which these forms of labour brought new meaning to the works of art being produced.

The research and topic were also tied to a particular moment in China's recent past—a moment of pre-Olympics hype and fast-paced expansion. At that moment many artists were ramping up production to meet the demands of the art market and I grew interested in exploring how artists were doing this on a material level. The spectre of production was everywhere at that moment—China was producing its image to the rest of the world via the Beijing Olympics, and the book became about how contemporary artists, for better or for worse, were also caught up in the spirit of making, building and producing.

ADIn terms of China, you wrote an article for e-flux where you identified one of the enduring dilemmas as being related to the government's own directives which consciously limit the interaction of art with society. Obviously Arrow Factory was a way of circumventing this. How are artists working to interact more with society?

PYRight. That article also came out of my observations about how contemporary art was developing in China in the mid-late 2000s. This period witnessed great advances in terms of the art market but at the same time art practices and art exhibitions were becoming increasingly sequestered in art districts and divorced from the space of everyday reality. Today, as younger artists strive to reach international recognition, I also wonder if the work too easily lends itself to prescribed formulas and methodologies. Finding artists or art practices that solicit sustained engagements with society or the local surroundings is not easy simply because it does not merge well with the demands of the Chinese art market. Take an artist like Zheng Guogu, for example. His daily life and artistic practice are fully merged into one so they become almost indistinguishable. But such ways of operating are hard to come by in bigger cities where one is forced to follow the tendencies of the art system.

Also, for someone like Zheng, the material of life becomes the subject and space in which to create art. As John Cage said, "Art is a sort of experimental station in which one tries out living". This is different from what many visual artists do today which is to borrow or draw upon aspects of daily life—events, narratives, objects, experiences—and use these as fodder for making a work of art.

ADHow would you define artists you are interested by?

PYTough question! I would have to say that I am most interested by artists who make the familiar unfamiliar, who can skilfully craft questions that interweave personal narrative with the various social and political contexts of the day, but do so with an air of utter conviction and precision. As John Baldessari said, "Great art is clear thinking about mixed feelings." As the landscape of contemporary art broadens and becomes harder to define, I find myself drawn to artists who are prone to investigating these ambiguities and questioning perhaps the biggest ambiguity of all: what it means to be an artist of this generation and what role an artist can play today. —[O]