Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven: The Dada Baroness Who Shook the Art World

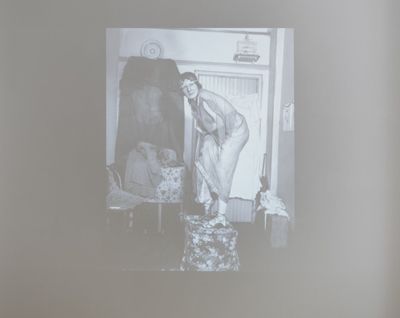

Projection of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven Working as Model (7 December 1915). From digital scan of a photograph. © International News Photography Bettman / Corbis / Magma Getty Images. Exhibition view: The Baroness, Mimosa House, London (27 May–12 September 2022). Courtesy the artist and Mimosa House, London. Photo: Rob Harris.

How could history forget the eclectic, mesmerising Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven—radical protofeminist, performance artist, and living, breathing artwork?

Von Freytag-Loringhoven, whom Duchamp called the future, was a visionary, even by today's standards. She ran in New York's Dada circles in the late 1910s and 20s, arriving at the readymade years before her peers with works like Enduring Ornament (1913).

The artist sighted the rusted metal ring the size of a child's bracelet on the streets of New York City en route to marry her third husband, Baron Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven.

The ring was declared the symbol of a lasting alliance, two years before Duchamp coined the term 'readymade'—a point that resonates with the disputed rumour that von Freytag-Loringhoven was the brains behind Duchamp's original urinal-turned-Fountain (1917).

Born Else Hildegard Plötz in 1847 in Świnoujście, the Baroness left home for Berlin at 18 to perform as a vaudeville artist. She married, modelled, and had affairs in Berlin, Munich, and Italy, before landing in New York's Greenwich Village in 1913, where she met the Baron.

While penniless, the Baron's title provided authority and became the foundation for the artist's life in New York, where she posed for other artists like American painter George Biddle, photographer Man Ray, and for classes at the New York School of Fine and Applied Art.

Biddle recounts their studio session in 1917: the Baroness arrived to pose nude, only to reveal her breasts covered in tomato tin cans, a caged canary around her neck, cropped vermilion hair, and a sleeve made of stolen shower-curtain rings.

Unsettling the expectation of the female nude, she extended an image that could not be mused over. Among other body-art assemblages, is the delicate earpiece Earring-Object (c. 1917–1919). Inside a glass container, a small pearl hangs from a curling steel watch spring.

Biographer Irene Gammel refers to the artist's commitment to an 'artistic law' of her own as a counter-resistance to the prescriptions of 'patriarchal law'. She abided by this law throughout her life, fighting for women in art and an art beyond the aesthetically pleasant.

One photograph from 1920 appears to officialise this self-contracted promise. The artist is seen in profile, aged and solemn; a crown has been drawn over her head, and her name is signed at the bottom as a vertical poem in carved letters.

Elsa, Baroness von Freytag-Loringhoven, Shaving Her Pubic Hair was filmed in collaboration with Duchamp and Man Ray the following year. Unfortunately ruined during its development process, a surviving still shows the artist's boyish frame posing nude, one toned arm flexed.

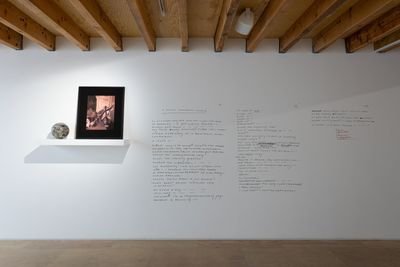

For the first time, von Freytag-Loringhoven's tenacity and enduring spirit are brought into conversation with 11 contemporary artists, poets, writers, and one collective in The Baroness at Mimosa House in London (27 May–17 September 2022).

Curated by Daria Khan, works by Libby Heaney, Dr Nat Raha, Nora Gomringer, and Reba Maybury, among others, respond to sculptures, images, and poetry from von Freytag-Loringhoven's prolific practice—among them, Earring-Object and Enduring Ornament.

On the wall by the entrance, two digitally incised giclée prints by Sadie Murdoch, Pathway Where-To and Pass-Way Into Where-To (both 2021), form portals through time. In each prints the Baroness' ghostly form is incised into the backdrop of a New York City apartment, where she posed in 1915 in a slew of outfits.

Contained within her form is a photograph of the door to Berenice Abbott's Paris studio. Abbott was a contemporary and close friend of the Baroness who photographed avantgarde figures like surrealist Jean Cocteau and novelist James Joyce, but never von Freytag-Loringhoven. (When Abbott left for Paris in 1921, the Baroness declared herself 'forgotten'.)

Von Freytag-Loringhoven, whom Duchamp called the future, was a visionary, even by today's standards.

In 1915, one New York Times reporter did photograph the Baroness, then known as the 'mysterious model' from the New York School of Fine and Applied Art. Posing in her apartment wearing a feather headpiece, patterned camisole, and striped trousers, the artist's body spreads across the frame, one arm and leg forward, the other two back; neck contorted.

This photograph is projected in a slideshow with other photographs of the Baroness on the gallery wall facing Murdoch's prints. On the adjacent toilet door is a projection of the famed urinal known as Fountain. Printed beneath the projection is a confession of the artist's former infatuation for 'Marcel Dushit', back when she was 'foolish'.

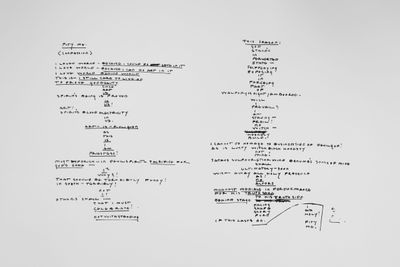

Poems in the artist's handwriting are also printed along the walls, dismembering language into sounds and breaths: short one-word verses punctuated by copious dashes.

Reading von Freytag-Loringhoven's ubiquitous use of the em dash as a symbol of castration and breathwork, artist Astrid Seme recovers the latter in Baroness Elsa's em dashes (2019), with enlarged vinyl em-dashes plastered along the walls to connect and disrupt other works.

But while Seme's vinyl prints remain quiet, the recording of the female voice narrating 'A Dozen Cocktails—Please', a 1927 poem by von Freytag-Loringhoven, reverberates through the gallery.

'WE HAVE ... NO BANANAS', the voice in the speaker reads; 'I GOT LUSTING PALATE–– I / ALWAYS EAT THEM.' The Baroness describes 'dandy celluloid tubes' of 'all sizes.' Words like these may explain why The Little Review, among the experimental magazines where von Freytag-Loringhoven published her poetry, came under attack for featuring the artist's sexually explicit writings.

Von Freytag-Loringhoven would often be dismissed as an eccentric in her lifetime—condemned perhaps, for being expressive in ways that exceeded even the avantgarde. In the undated poem 'Pity Me (Confession)', she speaks of the burden of her endearment towards life and her aesthetic consciousness. 'I LOVED WORLD', she writes, 'BECAUSE I COULD DO LOVE IN IT'.

With a distaste for the art market, the Baroness lived in poverty for most of her life and never sold a work. Sculptures were passed on to friends or dissipated into nature. In her poetry, art, unsurprisingly, is termed 'god' and 'religion', and she its 'priestess', while business is the 'devil'.

In a climate of post-war disillusionment, von Freytag-Loringhoven approached art and politics with matter-of-fact sincerity at a time when others turned to irony and conceptual distance.

Echoing this reality is the third and final sculpture by the artist featured in The Baroness. Placed on a shelf, the small tower-shaped Cathedral (c. 1918) contends with the fragility of modern faith. A thin fragment of wood with jagged edges supported by wire, it recalls New York City's skyscrapers and the promises of urban development.

Nearby, Linda Stupart's rescued-wood assemblage Cathedral (2022) forms a portal of intersecting branches spanning wall-to-ceiling, made from wood gathered along the River Cole in Birmingham, where the artist lives.

Considering nature as part of the already-there, if not the collateral damage of a post-industrial age, Stupart writes that her installation gathers 'cathedral fragments of the riverbank ... threatening to burst; like I am, like we are.'

Stupart's blunt, poetic statements echo those of von Freytag-Loringhoven's—words like the twisted drainpipe sculpture God (1917) that the artist ripped from photographer Morton Schamberg's studio, who was then credited for it.

Von Freytag-Loringhoven would stand her ground regardless of such erasures, asserting herself in what was predominately a man's world. In a portrait shot by Man Ray in 1919, she adopts a distinctly masculine demeanour, with hair tucked behind a large hat, a checkered jacket, and an austere expression.

Zuzanna Janin's 'Femmage a Maria & Elsa' (2018–2020) pays homage to this enduring legacy with three semi-transparent epoxy-resin orbs referring to the 'Maria Anto & Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven Art Prize' for women artists, conceived by Janin. Cut-outs of artwork images, portraits, and text fragments by Anto and the Baroness are enclosed within each.

Upstairs, two more resin works by Janin from the 'Home Transformed Into Geometric Solids' series (2018) recover scraps from Janin's former home in Poland, rebuilt following a 1944 bombing with bricks from the town neighbouring Świnoujście, where the Baroness was born.

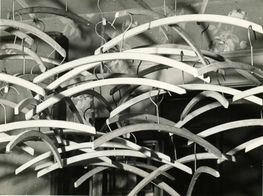

Surrounding the latter, four amautiit parkas—traditional Inuit outerwear with front pouches to hold children—hang from the ceiling like spectres. Forming Taqralik Partridge's Build My Own Home (2021), each garment is bricolaged from newspapers, tarp, dental floss, and tape, evoking both the 'homefulness' of building with simple materials and the homelessness of Inuit communities in northeastern Canada.

In a separate space, a seating area framed by three screens and curtains made from clothing present Liv Schulman's six-episode video installation, Le Goubernement (2019), a fictional re-imagining of the lives of lesbian, queer, and non-binary artists in Paris from 1910 to 1980.

On the central display is episode three, where an actress playing the Baroness is seen strolling down the streets of Montparnasse. She is asking: 'Do you see me? Masculinity is a Dadaist performance.' —[O]