Morocco’s Iconic New Wave: The Casablanca Art School

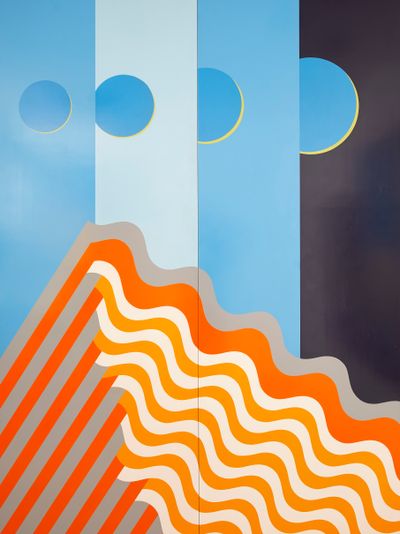

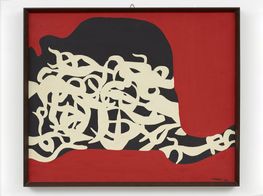

Mural by Mohammed Chabâa at Asilah Cultural Festival (1978). © M. Melehi archives/estate. Photo: M. Melehi.

History is often made when the right people end up in the right place at the right time. That fateful alchemy defines the story of the trailblazing artists who revolutionised modern art in post-colonial Morocco.

The locus of this movement was the Casablanca Art School (CAS), which underwent radical changes after artist Farid Belkahia took on the school's directorship in 1962 at age 28, six years after Morocco gained independence from French rule.

Returning from his studies in Paris and Prague, Belkahia approached the practice of pedagogy with the spirit of transnational activism that infused his artistic practice—early 1960s paintings recalling the figurations of Klee and Dubuffet supported Algerian independence and the Cuban Revolution.

Determined to break the French colonialist grip on arts education in Morocco, which diminished the importance of traditional crafts, Belkahia revolutionised the school's curriculum and structure to synthesise regional artisanal skills with modern applications. As he famously said, tradition is the future.

Soon rejecting canvas and paint in favour of contextual materials like copper and animal hide, Belkahia opened classes to women and brought in teachers whose approaches to fine and applied arts integrated traditions that define Morocco as a trans-cultural space.

Art historian and anthropologist Toni Maraini joined CAS in 1964 to devise Morocco's first modern art-history course, which was attuned to the contextual specificities of Morocco as an international region bridging the Mediterranean, the Arab world, and Africa. The same year, Mohamed Melehi became a visual arts professor at the school, followed by anthropologist Bert Flint in 1965, who led classes on Arab, Amazigh, Islamic, and Mediterranean heritage. Artist Mohammed Chabâa came on board in 1966.

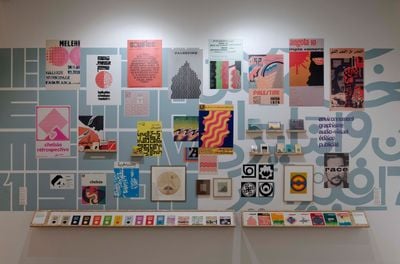

These five figures form the locus of The Casablanca Art School (27 May 2023–14 January 2024) at Tate St Ives curated by Madeleine de Colnet and Morad Montazami in conjunction with Tate St Ives Director Anne Barlow and assistant curator Giles Jackson: the first museum show in the U.K. to explore the legacy of CAS organised in collaboration with Sharjah Art Foundation.

Artworks by 22 artists associated with CAS—among them Chaïbia Tallal and Abdelkrim Ghattas—span paintings and murals, craft and graphics, interior design and typography, with archival images and documentation contextualising a transnational movement that was anything but provincial or derivative.

...Belkahia revolutionised the school's curriculum and structure to synthesise regional artisanal skills with modern applications.

Of the group, the most internationally renowned is Mohamed Melehi, whose brightly coloured, hard-edge minimalist paintings rendered in cellulose paint on wood board drew from the geometric patterns of Imazighen carpets, among other influences.

In Melehi's distinctive compositions, bold, dynamic stripes and waves line up in and against complementary and contrasting colours and grounds, as is the case with one untitled 1983 painting.

An irregular swell composed of orange, yellow, grey, and purple stripes cuts horizontally across a lime green ground sectioned by a thin, central column of blue and white stripes that extend outwards once they reach the image's top and bottom edges.

Melehi was a quintessential cosmopolitan, much like his Casa Group contemporaries. After studying in Spain, he went to Italy where he met artists Carla Accardi, Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, and Jannis Kounellis, and saw works by Jackson Pollock for the first time. He was also introduced to Zen philosophy, which Melehi associated with Islamic Sufism and described as the prism through which he read Pollock's paintings in association with jazz.1

'I went to the West to learn Western things, but at the same time I came upon Eastern things,' Melehi said, citing Japanese cinema, especially Akira Kurosawa's film Rashomon (1950), as a key influence at the time. 'This drove the evolution of my view on things.'2

Moving to New York in 1962, where his studio was located in the same building as Pop artist Jim Dine, Melehi participated in Hard Edge and Geometric Painting and Sculpture at MoMA in New York and Formalists at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art in 1963. The next year he returned to Morocco, where he would reconnect with Chabâa at CAS.

Chabâa and Melehi were well acquainted. They studied at the National Institute of Fine Arts in Tétouan, graduating in 1955, and saw each other in Rome, where Chabâa enrolled in the Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma and apprenticed with engineer and architect Pier Luigi Nervi.

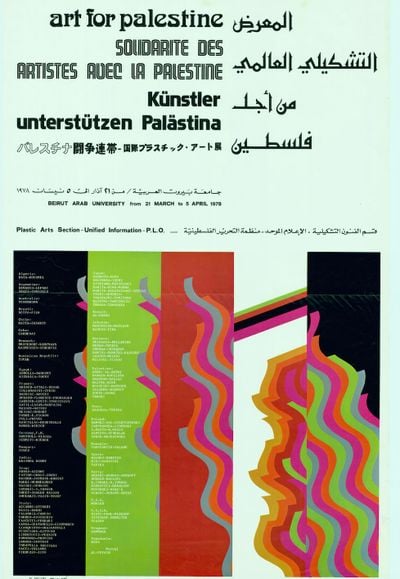

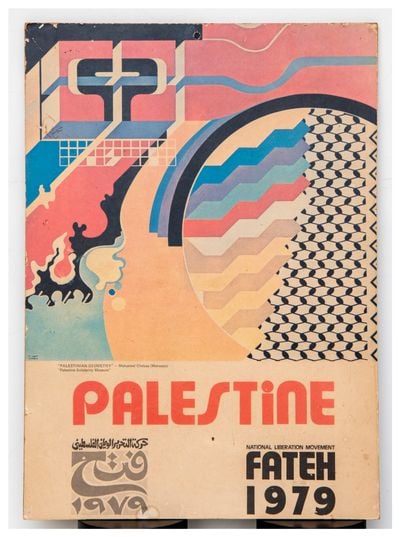

Indeed, they co-designed the democratic and decolonial cultural journal Souffles, established in 1966 by Moroccan poet Abdellatif Laâbi and banned in 1972, when Chabâa was imprisoned as a Marxist activist and Laâbi for cultural activism. They also designed the invitation card and poster for the 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine, organised by the Palestine Liberation Organization in Beirut.

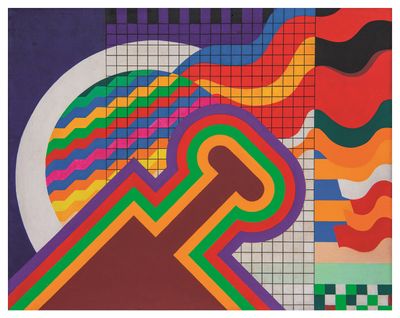

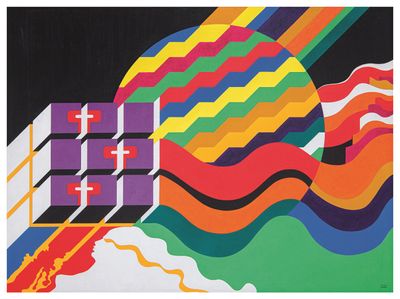

The connections between Melehi and Chabâa are striking in their resonant yet distinctive aesthetics. Also employing bright colours shaped into curves, waves, and stripes, Chabâa's compositions are more complex than Melehi's, if not more irregular in their geometries.

Two untitled acrylic-on-canvas works by Chabâa from 1977, for example, depict an intersection of distilled patterns that recall Wassily Kandinsky's exuberant jazz-age abstractions, only this time filtered through a singular, graphic hard-edge pop sensibility.

The connections between Melehi and Chabâa are striking in their resonant yet distinctive aesthetics.

In one, a three-dimensional block with a purple face sectioned like a Rubik's cube, shoots out from the bottom-left corner into the side of a two-dimensional circle filled with zigzagging lines of blue, yellow, pink, green, red, orange, purple, and white. Larger multicoloured waves emerge from the cube's side, before meeting a white wave at the bottom of the canvas whose outline reveals a woman's profile.

Chabâa, who described the poster as 'a painting that is accessible to all', incorporated Arabic calligraphy into classes exploring typography, graphic design, craft, and interior design. His approach reflected the cue that Casablanca Art School took from both the Bauhaus school and Maghrebi artisanal traditions, collapsing distinctions between art and design.

At Tate St Ives, the connections between Melehi and Chabâa are striking in their demonstration of a resonant yet distinctive aesthetic.

Both Chabâa and Melehi's influence can be seen in the work of CAS student Malika Agueznay, who participated in the 1968 annual Casablanca Art School exhibition, a landmark show that demonstrated the impact the new Casablanca Art School was having on its students.

Agueznay presented six painted wooden panels totalling around 3 by 4.5 metres, with surfaces covered in the artist's characteristic Matisse-like seaweed motif painted in burnt orange and dark blue against a light blue background.

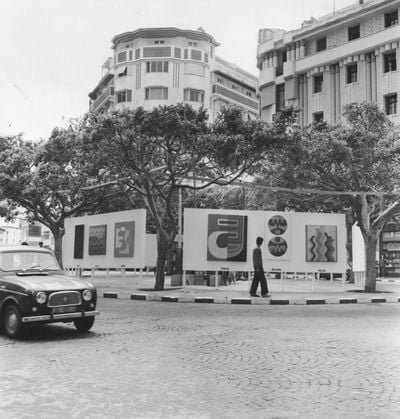

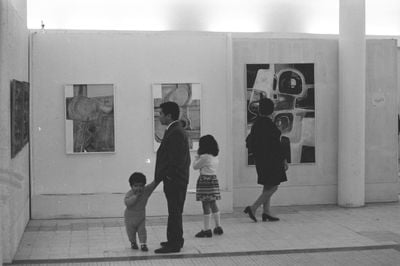

What followed in May 1969 was Présence Plastique, an outdoor exhibition staged in Marrakech's Jemaa el-Fna Square, an ancient trading crossroads, showing works by Belkahia, Melehi, Chabâa, and recently appointed CAS professors Mohamed Ataallah, Mustapha Hafid, and Mohamed Hamidi.

Recalling the 1863 Salon des Refusés, an exhibition showcasing works by artists—among them Gustave Courbet and Paul Cézanne—rejected by the Paris Salon, Présence Plastique protested the French-founded Salon du Printemps exhibition in Morocco, which classified Moroccan artists as naïve. In a joint statement, the artists said they wanted to engage people outside the galleries and salons they had never entered.

Présence Plastique travelled to 16 November square in Casablanca in June 1969, followed by showings at two girls high schools in Casablanca in 1971, further extending the Casablanca Art School's ethos that art was part of daily life.

This vision was extended by collaborations with architects like studio Faraoui & de Mazières, who designed interiors for Casablanca's National Bank for Economic Development and the National Tourist Office, among other sites, with interior interventions by CAS artists and those they invited to participate.

Among the artists included in a section exploring these architectural interventions at Tate St Ives is Carla Accardi, whose interrogation of calligraphic scripts through the lens of Abstract Minimalism resonates deeply with Agueznay's work and those of her CAS contemporaries.

In 1974, the final year of Belkahia's CAS directorship, the first pan-Arab Biennial took place at Baghdad's Museum of Modern Art in Iraq. Works by 14 artists related to CAS stood out among more than 600 artworks on view, announcing Morocco as the centre of a new wave in Arab modernity. In keeping, CAS artists became key protagonists in organising the second pan-Arab Biennial held in Rabat, Morocco, between 1976 and 1977.

Although many teachers associated with Belkahia's tenure had left CAS by then, the influence of the pedagogical revolution in Moroccan art that he and his colleagues instigated extended well beyond the school itself.

In 1978, Mohamed Benaïssa and Melehi co-founded the Asilah festival, which sought to instigate positive and sustainable development in northern Morocco, through street and gallery exhibitions, community mural projects, lectures, and concerts involving artists from Africa, the Arab world, Asia, Europe, and the United States.

Toni Maraini led children's workshops for that first event: 'We wanted to reach the general public where they live, in a casual and accessible way,' she explained.

Benaïssa later became Morocco's Minister of Culture, among other appointments. In 2004, he recalled the children who experienced the festival's launch, who had by then reached their thirties. This was 'a generation who has opened its eyes and has been influenced by art,' Benaïssa said, 'as a medium to enjoy life, and also to mobilise the resources of imagination and creativity.'3

In keeping with the fusion of art and life that CAS encouraged, the festival continues to this day. —[O]

1 Morad Montazami, 'Mohamed Melehi in conversation with Morad Montazami', Third Text, 12 February 2021.

2 Morad Montazami, 'Mohamed Melehi in conversation with Morad Montazami', Third Text, 12 February 2021.

3 Pat Binder and Gerhard Haupt, 'Mohammed Benaïssa: Asilah Festival', Universes in Universe – Worlds of Art, June 2004.