Huma Bhabha’s Monstrous Humanity

The Setup, Huma Bhabha's first exhibition with Xavier Hufkens at the gallery's Rivoli space (9 September–16 October 2021), showcases new sculptures and works on paper expressing the artist's characteristic alien forms.

Huma Bhabha, Untitled (2021) (detail). Ink, gouache, acrylic, pastel and collage on paper. 60.3 x 87.9 cm. Courtesy the artist and Xavier Hufkens, Brussels.

Among them is the fleshy Open Door (2021): a puckered head with an amasunzu-like crown resting on a stretched neck. Made from clay, plaster, wood, acrylic, wire, and jute, the form appears both in a state of erosion and formation, finger prints and dents creating a surface that seems to melt and undulate.

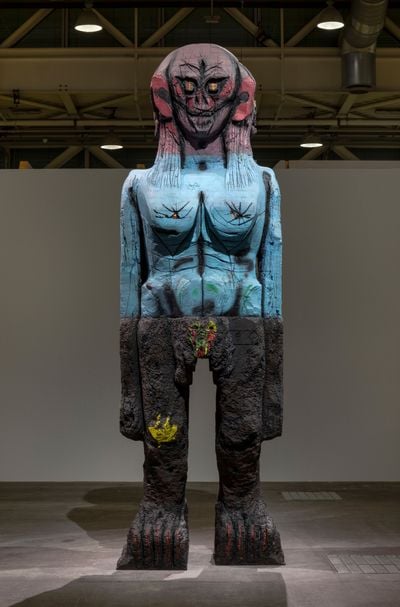

Often, Bhabha constructs her figures using rough materials before casting them into bronze; a classic example being We Come in Peace (2018), named from a line in a movie about an alien landing in Washington D.C., The Day the Earth Stood Still (2008).

Carved from Styrofoam and cork then cast into bronze, this 12-foot alien, Predator-esque kouros—with its many-faced red head, blue body, and black legs marked by sharp, expressive lines—was positioned on the Metropolitan Museum of Art's roof in 2018 as part of the Roof Garden commission that year. It towered over Benaam (2018), an 18-foot-long prostrated raw clay figure shrouded in an oil-black body bag.

Melded into these future forms—indeed, scratched, carved, and marked—are references running the gamut of art histories.

After snowfall covered the Met roof, Bhabha likened the scene to a Kurosawa film—had Kurosawa made a movie about an extra-terrestrial's arrival on earth. Bhabha put it another way in conversation with curator Negar Azimi: 'Think The Burghers of Calais meets a Marvel comics movie.'1

Movies, and in particular science fiction, infuse Bhabha's work—'science fiction lets me feel less alone in my paranoia', she has said2—even naming her 2019 solo exhibition at ICA Boston after John Carpenter's cult 1988 sci-fi classic about an alien invasion, They Live.

'One of the ways I like to approach the past is in a cinematic way,' the artist told Massimiliano Gioni, 'reimagining the past and projecting towards the future, just as movies often do.'3 This temporal fusion comes through in the title for another new sculpture, The Interlocutor (2021): a totemic figure carved from cork, with dark lines in acrylic, oil stick, and lipstick carving out details that seem to blend the forms of a neolithic stone figure and an owl.

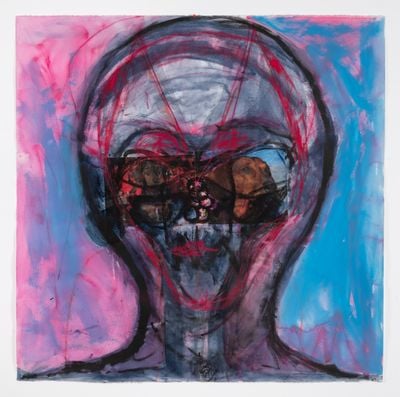

Melded into these future forms—indeed, scratched, carved, and marked—are references running the gamut of art histories. From classical antiquity, African sculpture, and the hybrid artistic legacies of Gandhara, to the 20th-century artistic canon, with Francis Picabia's overlapping lines coming through in portraits on paper that depict Bhabha's characteristically multi-dimensional alien faces.

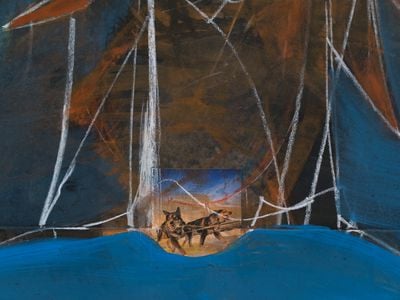

One ink, gouache, acrylic, pastel, and collage on paper from 2021, on view in Rivoli, presents a horned face built up from energetic marks that look to the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Georg Baselitz, its white-bone core popping out of a blue-brown ground. Layers of pigment build a sense of emergence—Bhabha's aliens are perpetually caught in a state of arrival and encounter—and fine lines at times create the illusion of fine fur.

Such otherworldly narratives cut to the heart of the artist's focus, which draws on her experience of living in the United States and having to contend with her own otherness.

First, as an undergrad at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she began incorporating found materials into her work, looking to Robert Rauschenberg and David Hammons, and as an M.F.A. student at Columbia University, where she graduated in 1989. Then, as a resident of Poughkeepsie, where she moved in 2002 as the so-called war on terror reached fever pitch.

But while there is an anti-war statement embedded in sculptures like We Come in Peace, Bhabha does not want her work to be limited to singular interpretations. 'It's the monster I connect with,' she told Azimi, who tracked the root of the word 'monster' to the Latin 'divine omen', and the Old French 'an animal of multiple origins'.4

In Bhabha's world, the monsters are more human than those who invoke humanity—say, human rights—in their wars.

'The monster, and other forms of the monstrous and grotesque, inspire me', Bhabha continued; which is a key to thinking about the terrifying forms she represents—beautifully rendered but menacing; powerful but delicate; monstrous but resolutely earth-born.

In fact, Bhabha's portraits recall those conjured by Pierre Huyghe's Mental Image works, created with a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) machine that scanned people's brains as they looked at pictures of life forms and artworks. Huyghe then fed the information into a neural network that compared them to an existing image database before rendering their own, uncanny interpretations.

There is a sense that these are the kinds of images that Bhabha creates manually; of a hybrid future that is horrifying for some and a comfort to others who are already living in that state of sheer complexity. Where structures and bodies can rarely be contained, because they never stay still for long.

Bhabha put it this way when she equated there being 'no such thing as one side of the line' in response to how her own life has fed into her mark-making.

She mentions apartheid South Africa, where her father was raised, and 1979, when Iran's revolution erupted and Russia invaded Afghanistan: part of a proxy war whose horrors reared their head amid the disastrous NATO withdrawal from the country after a 20-year occupation in August 2021.

'Notions of purity, nationalism, and patriotism are extremely disturbing and heinous to me', Bhabha has said5—something that has become ever more visible in a world of false idols. In Bhabha's world, the monsters are more human than those who invoke humanity—say, human rights—in their wars. —[O]

1 Negar Azimi, 'Work in Progress: Huma Bhabha', Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2019, Accessed 3 September 2021, https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2019/11/12/interview-huma-bhabha/

2 ibid.

3 Massimiliano Gioni, 'Interview: Huma Bhabha', Kaleidoscope (Summer 2016): p. 124–131.

4 Negar Azimi, 'Work in Progress: Huma Bhabha', Gagosian Quarterly, Winter 2019, Accessed 3 September 2021, https://gagosian.com/quarterly/2019/11/12/interview-huma-bhabha/

5 ibid.