An esteemed pioneering figure in South African photography in the 20th and 21st century, David Goldblatt's career spanned over 70 years. The Randfontein-born photographer, as an insider, witnessed and chronicled South African history. From the rise of Afrikaner nationalism to the apartheid regime and the new democratic era, he captured the moment through the country's landscapes, structures, and people.

Read MoreDavid Goldblatt's photography from the outset has been focused on defining the nature of the society he grew up in. Goldblatt was born to Jewish parents in the South African mining settlement of Randfontein. He grew up serving the Afrikaners and others working in his father's clothes business.

In 1963, after Goldblatt's father passed away, the budding photographer sold the family business to pursue a full-time career as a professional photographer. Over the next few decades, Goldblatt worked as an editorial photographer at magazines like South African Tatler, and later worked on current-affairs publications like Leadership and Optima. His images, however, often sought to satisfy a personal curiosity and mission.

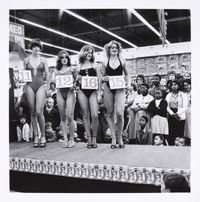

For David Goldblatt, biography and practice often overlapped. In his earlier photobooks such as Some Afrikaners Photographed (1975) and In Boksburg (1982), Goldblatt honed in on the kind of people he grew up with and served in his fathers shop. With these Afrikaners he explored the idiosyncratic contradictions between their apparent warm and down-to-earth friendliness and the extreme prejudice of the racist society they reigned supreme over.

Furthering that contrast, Goldblatt also documented life for the black and Indian populations, increasingly displaced while often working in areas 'reserved for whites.' The artist explained in an interview for San Francisco Museum of Modern Art that he hoped, through the reality starkly shown in these images, his South African compatriots might see the abnormality and madness of everyday life at the time.

David Goldblatt's apartheid photography is subtle in its protest compared to other anti-apartheid artists. It looked beyond violent events, instead expressing the social conditions behind them. As Goldblatt once explained 'During those years my prime concern was with values—what did we value in South Africa, how did we get to those values and in particular, how did we express those values?' This applied as much in the apartheid era of his work as any.

Through his photography Goldblatt examined how South African's values were expressed in both physical and ideological structures. In every bus shelter, footbridge, walled estate, shack, township, and monument, choices were made that reflected the preferences and values of those who made them. The artist sought to capture these choices.

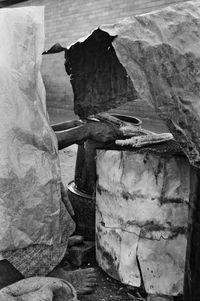

People and their bodies also came into this exploration of values in David Goldblatt's photographs. Books like Particulars (2003) present his efforts through photography to examine how these values play out even in focused images of parts of people's bodies, black and white. The fall of cloth on a thigh, breast, or hip, rough hands, the movement of tendons in a foot, or limbs in repose were political because the body is political.

The idea of capturing a society's values and identity through photographs of people, structures, and landscapes remained a focus in Goldblatt's post-apartheid work too. From 1999 to 2011 the artist travelled the country, taking colour photographs and documenting places of intersection—both physical and conceptual. Goldblatt also personally explored another aspect of modern South Africa—as well as England—in 'Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime' (2008–2015), meeting, photographing, and humanising those who committed the crimes.

David Goldblatt's documentary photography, while made with a South African audience in mind, has found international appeal. His work has been exhibited in major institutions and galleries world-wide, as well as international art events including Documenta and the Venice Biennale. Goldblatt's photographs can be found in major public collections including The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and the South African National Gallery, Cape Town.

The famed photographer's legacy extends beyond his own body of work. David Goldblatt continually supported other South African photographers, and in 1989 he founded the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg—an institution that has educated other South African photographers, such as Zanele Muholi and Musa N. Nxumalo.

David Goldblatt: 1948–2018, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney (2018); Structures of Dominion and Democracy in South Africa, Minneapolis Institute of Art (2014); TJ 1948–2010, Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris (2011); Intersections Intersected, New Museum, New York (2009); Intersections, Museum Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (2005); Fifty-one Years, Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona (2002); David Goldblatt, The Museum of Modern Art, New York (1998).

On Common Ground, Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg (2019); Apartheid and After, Huis Marseille, Museum for Photography, Amsterdam (2014); Figures & Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography, Victoria and Albert Museum, London (2011); History/Memory/Society, Tate Modern, London (2004); In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (1996).

Michael Irwin | Ocula | 2021