Heinz Mack

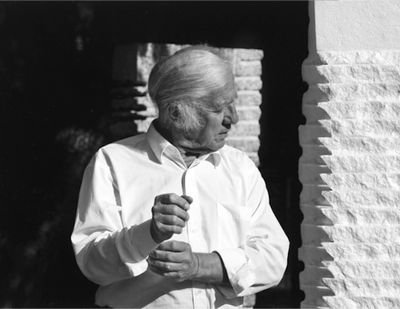

Heinz Mack, 2008. Credit: archive studio Mack.

Heinz Mack, 2008. Credit: archive studio Mack.

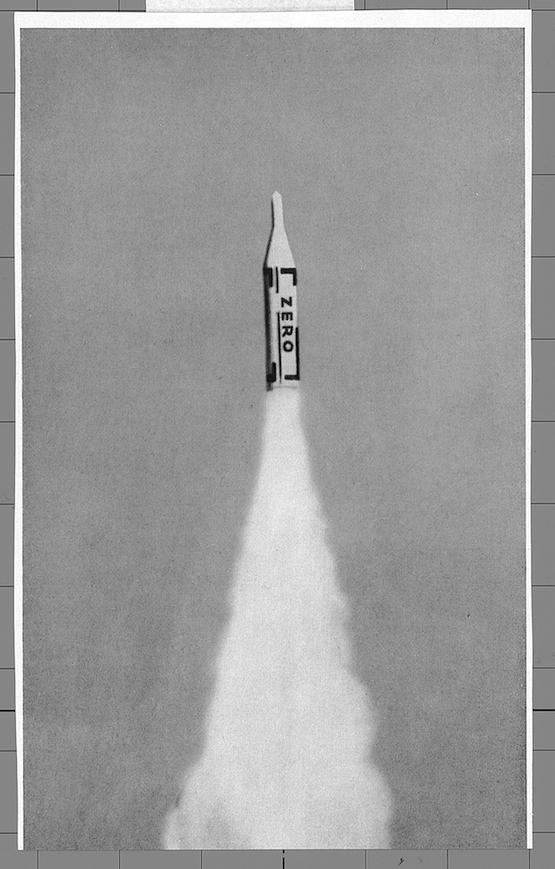

A pioneer of land art in Europe through his iconic 'Sahara-Project', Heinz Mack is one of the founders of ZERO, which he started along with Otto Piene, whom he met in 1950 when both were students at the legendary Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf. Mack and Piene became collaborators, co-founding the ZERO movement in 1957, by establishing a magazine while staging shows and happenings at their studio.

In 1961, Günther Uecker joined the group, which emerged out of post-war Germany and soon ZERO evolved into a network of artists from Europe, Japan, and North and South America, including Yayoi Kusama, Piero Manzoni, Almir Mavignier, Jan Schoonhoven, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely and Yves Klein. Officially lasting until 1966, the movement has since been the subject of a major exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York, ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s–60s, which was the first large-scale historical survey in the United States dedicated to ZERO (10 October 2014–7 January 2015).

The exhibition features more than 40 artists from ten countries, and explores the experimental practices developed by the extensive network of ZERO artists, whose work anticipated aspects of land art, minimalism and conceptual art.

In this discussion, Heinz Mack considers the contexts from which ZERO emerged, and remembers the vital meetings that took place, recalling how relationships formed, particularly with Yves Klein, Jean Tinguely and Lucio Fontana. He also considers the environment in which the movement unfolded: a vibrant time not only in Düsseldorf but also in the Rhineland in general, which saw a lot of artist traffic from those practising both within the region and abroad. Mack provides some colourful views of Nam June Paik and the first Fluxus festival in 1962, Joseph Beuys and the Capitalist Realists.

SBZERO began with a magazine you founded and worked on with Piene; you also staged shows and happenings at your studio, which is how you began to work with Günther Uecker, who formally joined the group as a member in 1961. Would you talk about the evolution of ZERO from the establishment of the concept, to the moment you, Piene and Uecker came together?

HMDominating was the reality of handiwork in our workshops. Each one of us worked alone, experimenting with colour and light, or, in my case, the concentration of space in its relation to the sculpture and vice versa. All this went along with recognitions, perceptions, ideas and some intellectual effort. Piene and I discussed our experiences and this led to a conception—a getting to the bottom of a kind of theory containing the principles of clearness, motion, vision, energy, pure colour and light, and their appearance in space as well as their reception in our eyes. Furthermore, instead of using the old-fashioned principle of composition, we developed the new principle of structures and serial interferences in a logical interflow of rhythmic elements. In the case of Piene and Uecker, these elements are points, while in my case I used lines in their parallel structure, which intercommunicated.

In general, our studios were workshops, platforms for discussions and were used occasionally as gallery spaces, opening for one-night events, or used as meeting points for a few artists and friends. The first magazine was an attempt to publish our main ideas and to offer it to public discussions. All this happened after we left the academy in 1953.

SB1953 was the year you graduated from the Kunstakademie; after this you went to Cologne to study philosophy. What made you choose philosophy?

HMThe short answer is this: to be accepted as a teacher in a secondary school, the category of being an artist was not enough. You had to take the state examination for sciences, and philosophy was one of the offered subjects. You should take into consideration that ZERO started in 1957, so between state examinations and the beginning of ZERO, there was a certain period in which we were learning to become teachers.

SBAnd how did your work develop during this time?

HMAfter World War II, we were in what you might call a vacuum: nothing was left—we had been left absolutely blind. Even in the library of the well-reputed Academy in Düsseldorf, there were three or four old books left; there was no information at all! To give you a simple example, because I worked quite hard as a student, I received a scholarship from the state—just enough money to go from Düsseldorf to Paris by train. I was so happy and so excited to see, at the Grand Pavilion, paintings by Picasso, Miró and Matisse for the first time. When I came back a week later to my academy in Düsseldorf, I told my friends about a very strange artist I'd never seen before, Miró, and nobody, not a teacher or a student, had ever heard his name!

Then there was of course something I would like to state as fact: in the 1950s, the CIA started to sponsor American artists worldwide by sending their works to embassies and museums, so all these countries got a chance to look at the works. So the very first paintings I saw by Rauschenberg and Lichtenstein, for instance, I saw in the American Embassy in Bonn; and these were nothing like the European works being shown in the galleries or museums at the time.

What I perceived between this very high level of communication, publication and information, sponsored by the CIA on behalf of the USA, was in huge contrast to our situation: we were poor and didn't know much about anything. Of course, it is important to mention this: the epicentre of American Pop and conceptual art collections was gathered in Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, by collectors such as Peter Ludwig, who founded the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, because money was not an issue and he bought whatever he could get, with a high sensitivity for quality. Soon, you had artists like Lichtenstein complaining that their best work was ending up in Germany! During this time we were also influenced by what was happening in Paris, because then Paris was the capital of Modern art, and the centre of Art Informel.

SBHow did your work evolve during this period?

HMAfter World War II there was a deep depression, and this was conquered by intellectual discussions. Whatever has been done by German artists who are now celebrated: Richter, Baselitz, Neo Rauch or Kiefer, for instance; they are all fighting with the problems of World War II, somehow. Yet, the Americans seem fascinated by German expressionist-artists who act like wild beasts: this fits with this judgement and trauma that the Germans are wolves—even German Expressionism of the Golden Twenties was dependent on the First World War. It's very typical, too, that some people would develop their own mythologies around this, like Joseph Beuys, who I once told not to expect me to have any interest in his private mythologies, though he was free to have them. He said that it made sense that I would not understand it, to which I replied, 'I was lucky that I didn't.'

So I remember for one summer, I painted like a violent man. This was followed by a deep depression and I don't hesitate to mention this, too. During this time, I asked myself: 'What could I do to find a new approach?' This was really a moment of desperation and for a while I thought about giving up on this kind of art. This was in the 1950s, and it was then that I went to Paris to find the studio of Brâncuşi, which I found with the assistance of Jean Tinguely, whose office was next to Brâncuşi's. When I got there, the door wasn't really closed, and for me, it felt like discovering Tutankhamun's tomb, standing absolutely alone in this huge studio as Brâncuşi had left it before he died. It was dusty and dirty, but everything was in its complete original state. I was so impressed. This is when I started making the move towards being more of a sculptor than a painter.

SBHow did ZERO relate, or not, to what was happening in the region and particularly in Düsseldorf, from the Kunstakademie and its faculty and students, the influence of Nam June Paik and the first Fluxus festival in 1962, to the happenings of Beuys at the gallery of Alfred Schmela, for instance, or the work of the Capitalist Realists: Polke, Richter, Kuttner and Lueg?

HMAt this time, informal art was becoming famous, and the Fluxus festival in 1963 showed up with some background noise and theatrical nonsense à la 'Dada.' Informal painting seemed to be a last reaction to the ruins of World War II: sloppy paint and full of pep and wild gestures and filthy wrinkles and antique oxidations—all of this was hated by Piene, Uecker, our ZERO friends, and myself.

Nam June Paik seemed on the one side to be a complicated compound between Dada jokes and intellectual humour; on the other side he was seriously fascinated by technical inventions related to music, television and poetry. In those days he was not more known than we were; very few people knew about his work and experiments.

Beuys was a kind of highlight of all provocative events, which we did not like at all. He seemed to appeal to a kind of Tibetan or Indian occultism, clothed in a private myth, devoted to and admired by a lot of disciples and pseudo-religious followers. He transformed banal relics of daily life into sacred objects, like symbols of salvation. His philosophy was preponderant, confusing and presuming. Nobody of the ZERO gang was influenced by Beuys and the Capitalist Realists. They did not feel holy like Beuys: rather, they preferred to provoke prude bourgeois behaviour and civilian attitudes by ironic reflections. For a certain while there was some connection between Uecker and Richter: they made jokes with each other and their surroundings, the way students do.

SBSpeaking of influences and non-influences, I'd like to discuss Yves Klein's relationship with ZERO ...

HMActually, it was Jean Tinguely who asked me if I'd ever heard of Yves Klein, and it was Tinguely who took care of it so that I met him [Klein] in Paris. It was exactly the time Tinguely produced a construction with a little motor on top of it that could spin around, on which Klein added a little disc of paper—a coaster—on it, coloured monochrome-blue. Tinguely and Klein told me proudly that this was what they had been collaborating on, and they asked what I thought of it. When they turned it on, immateriality was the main thing that stood out for me: the colour of this rotating disc became completely immaterial, like a blue cloud at once spinning but seemingly static. They were so happy that I immediately discovered the sense of it! This was a very important meeting.

After this, it was just a matter of weeks until Mr Alfred Schmela asked Uecker and myself about how he should start his gallery, and with what exhibition he should launch. During this period, Norbert Kricke, a very good sculptor in Germany, met Klein and suggested to Schmela that he show the monochrome works in Düsseldorf. I supported this, which resulted in Klein's 1957 exhibition,Yves, Propositions monochromes. So you see, things kind of happened almost by accident; everyone was influencing and impressing each other at the same time and reaching out in different ways. There was no hierarchy: it was really more about equivalence between artists.

SBWas this the case with Lucio Fontana? I am thinking here of the kinetic sculptures you presented at documenta 3 in 1964, now a permanent part of the Museum Kunstpalast Museum collection. As this installation was inspired by Lucio Fontana, I wonder if you could elaborate on the relationship you had with him?

HMThe same thing that happened in our friendship with Klein happened with Lucio Fontana. Fontana was a kind of colleague who supported and inspired us, giving us this affirmation and awareness that we were on the right path. Of course, he was old enough to be my father, but you never got this feeling from him. And his work was so useful to us; so near to what we were doing. When I had my very first exhibition at Iris Clert in Paris in 1957, which was shortly after Klein and Tinguely's joint show at the same gallery, I put a little relief sculpture of the desert in front of this little window—the show was a chance to present my 'Sahara-project'—and nothing sold except for this one little work. One year later or more, I went to Milan and I met Fontana in his studio for the first time. When I entered, I couldn't believe it: on top of his shelf there was my little relief sculpture! When I asked him how he got this he told me that he bought it from that show.

This is a really symptomatic example of the connections between the artists that formed during this time: artists sponsored each other by exchanging and discussing their work, their ideas and the problems of the world. It was a really exciting time: more and more artists working in different parts of the world were working with similar ideas without knowing what was happening in other places. This is a phenomenon that you cannot explain; that from Düsseldorf to Rio de Janeiro, all these artists had an idea that there was a new direction to participate in and follow. This was completely different to what happened in New York.

SBThis also relates to the ZERO aesthetic and the desire to move on from the legacies of World War II, while moving away from the tendencies of Abstract Expressionism ...

HMWhatever we had learned, we decided to forget, which is very complicated: to make a declaration to yourself to forget about everything and let go of everything you had done. And this came with a deep and almost unconscious desire to start from the real beginning. Actually, I had experienced this kind of discipline, as you might call it, perhaps also unconsciously, by taking piano lessons when I was younger. I had been encouraged to become a pianist, but I didn't do it. Trying to perfect a complicated work by Schubert with ten fingers, for example: nothing was perfect. There was always a moment that didn't work. And in those moments, I remember one teacher telling me to start from the beginning, with just one finger. A little of this spirit happened to us when we started ZERO: standing in front of an empty canvas and facing this horror vacui. We did this because we didn't want to follow Art Informel, nor did we want to follow Pop art or Abstract Expressionism.

So it was a matter of mediation and concentration: of feeling completely alone, with no one around assisting you. You became aware of the fact that whatever you did should be a document of your own existence; therefore it should not be a kind of entertainment, but something that gives you a certain reason for doing art at all. This idea of doing things 'just for fun' did not fit. There was a real awareness of the fact that everything had been destroyed after the war—his was not only the destruction of the material world, but also of the intellectual world. It was really this pure emptiness, which goes along with philosophy, of course. We were really impressed by the philosophy of Husserl; existentialism became so important, and it started with Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche, and then it became actual by Sartre and Heidegger; Albert Camus was very important for us, as was Kafka.

One of the philosophical views we worked with was that there is no heaven and there are no angels. Whatever should be done in your time and your existence in this world should be done here on earth: you are dependent completely upon yourself. And what you develop in your personality you cannot leave up to a teacher or a colleague, but you have to do it on your own. In another sense, it was important to think that other artists had the same feelings and were engaging in similar actions and approaches to working with all these problems. This goes along mainly with the philosophy of Karl Jaspers and existentialism: Jaspers made clear that each person is alone, individual, completely isolated, and at the same time there are also other individuals around who can reach out to each other. This could then be raised to a group mentality of community and interaction. Nevertheless, you are not to forget for a single second that you are alone: friendships happen between singulars.

SBWhich relates to the concept of ZERO as a networked movement ...

HMThis is something very important that I would like to mention. There is a special aspect to ZERO, completely unknown in some respects, and as long as I am alive, I will try to inform people. Through this experience of development, we formed what we call nowadays a network. I think it makes more sense to use this expression, 'network,' if you consider how ZERO is often seen as the last European avant-garde, or how it is perceived as a historical movement. But at the same time, since all these artists in different countries had been at one stage in connection to one another, this word 'network' goes along with the fact that a net can capture everything, and can hold things together that might be lost if they are alone. I think this is very important to keep in mind.

SBWhat characterises the artists of ZERO?

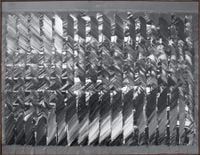

HMThe main thing is that all the artists that were or have been involved in the spirit of ZERO in general are working with structures. These artists are making concrete not realistic work: it's just structures—and behind these structures is the idea of light, space and movement.

SBHow does your work fit into this?

HMFor me, light is immaterial, and in my case, I prefer to make works that are instruments for light. My sculptures do have a kind of function: of making light visible. If you look at some examples, of course there is a certain similarity to what you can see if you look at the sea and if the sun is shining on the sea and there is a wind that makes the waves reflect the light in a particular way—there is a certain similarity to what happens in nature in the work, but it's not comparable with nature. It's not an illusion of nature: it has its own reality.

SBThis reminds me of The Sky Over Nine Columns, the installation you presented parallel to the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, in which you installed a grid of nine seven-metre-high golden columns in the waterside church square on the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. You said that the column represents man standing upright with dignity in space ...

HMYes. That means a lot to me: humanism, the community of man.

SBWhich recalls one of the tenets of ZERO: to produce work that was void of emotion in order to give space to the viewer; to allow space for reflection, or what you might call a philosophical garden, or as Otto Piene called it, a 'zone of silence'.

HMRight: to give space to emotions. Whatever I told you should be considered in a dialectical way because I explain what I can describe by words but there is another world belonging to what I want to explain which you cannot describe with words. This is very distant to conceptual art that depended completely on reason and wanted to control everything, as in mathematics. I told them they were poor, because the world is far richer. But there was a certain anticipation of what went on with the reduced world and conceptual art.

I am an older man—almost 84—and I can say that whatever I have done, more or less, was made for nobody as well for everybody. I don't accept this mentality that art is only available to a very small section of society that can afford it as a kind of luxury entertainment. Of course, we must not complain, but it's a fact today that art has become a stock. I cannot follow this anymore. Many things are going on in the arts, which might be interesting in terms of psychological behaviours. Many people have problems with themselves and they want to express it. But what is important about the work done by ZERO was this readiness to take responsibility for things in a very personal way, so that subjective behaviour becomes objectivised. Objectivism is so important: it is a condition that allows everyone to at least grasp what is being expressed: to touch it. —[O]

This interview was conducted with the kind support of the Arts Foundation NRW.