Come Together: Art Basel 2015

There was a celebratory atmosphere more often associated with Art Basel’s Miami edition: the parties were unbridled and sales were fast and furious

There was something different about Art Basel this year, and it wasn’t just the redesign of the first floor in Hall 2, or the reshuffle of Hall 1, in which Magazines and the Conversations sections were placed at the entrance preceding Unlimited. There was a celebratory atmosphere more often associated with Art Basel’s Miami edition: the parties were unbridled, sales were fast and furious; even the protests against the fair on the Messeplatz weren’t broken up by teargas.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Nikolaus Hirsch, Michel Müller and Antto Melasniemi, DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY. Art Basel in Basel 2015. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art BaselCertainly, the atmosphere was aided by the free food being served on the Messeplatz daily by Rirkrit Tiravanija, Nikolaus Hirsch, Michel Muller, and Antto Melasniemi and their team as part of the project—or social experiment—DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY: an outdoor kitchen from which visitors were served on the condition that they cleaned their own dishes (a new experience for some). This sense of camaraderie radiated out from the art fair, too, into such events as The State of Current Situations, a party held in a down-and-out space in Lehenmattstrasse in support of an off-space in Athens, Greece: a party at which it didn’t matter if you lost your friends, so long as you had the legs to dance. (Spotted guests included artists Anicka Yi and Vincent Fecteau, both exhibiting at Kunsthalle Basel.)

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Nikolaus Hirsch, Michel Müller and Antto Melasniemi, DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY. Art Basel in Basel 2015. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art BaselMaybe the buoyancy was in part due to the welcome return of Unlimited’s quality. The buzz was unanimous on the opening night: this was the best edition in some time. (Even if curator Gianni Jetzer’s obsession with walls proved too much for some—apparently Jetzer called for “more wall!” right up to zero hour, with the ever-wonderful artist, Sheila Hicks even commenting on Jetzer’s structural fixation during their Salon talk.) Perhaps the atmosphere had everything to do with Kenneth Anger’s monumental three-screen version of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, 1954-2014, positioned right at the entrance.

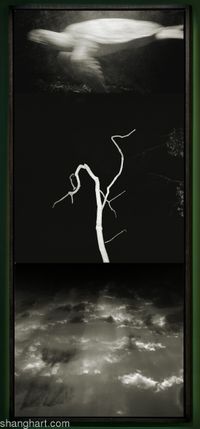

Kenneth Anger, Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, 1954-2014. Art Basel in Basel 2015. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art BaselThe 2014 version of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome is a short cut of the original 38-minute work Anger produced in 1954. It features a whole series of pagan idols, from Aphrodite, Kali to Pan, and pays homage to the philosophies of Aleister Crowley, and the concept that love is the law and one should follow one’s true will. The Unlimited installation was an immersive experience. Stepping into a dark room, the sounds of Electric Light Orchestra (added to the 1978 version of the work) mirrored the way male and female archetypes faded in and out of each screen during what is a rich and dense seven minutes. Sound and visuals build up to a crescendo of untold transcendence and expressive absurdity, recalling the fact that Anger was apparently inspired to make the film after attending a Halloween party called "Come as your Madness."

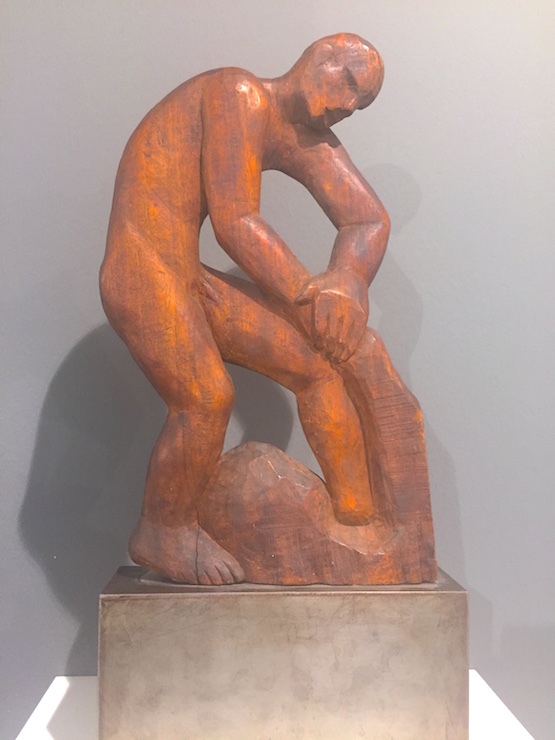

In this, Inauguration felt like a strange baptism. It coloured the way I viewed the rest of Unlimited, and indeed, Art Basel as a whole. Upon entering floor one of Hall 2, for instance, I was struck by the prevalence of the body as subject. There were a plethora of dirty drawings extracted from the oeuvres of masters: from a pair of penis-filled sketches by Yves Tanguy at Galerie 1900-2000, to Gustav Klimt’s Masturbating Girl (c1916) at Richard Nagy, who also showed a series of Egon Schiele drawings, including a woman with spread legs and a lady in a striped dress touching herself. Then there was a remarkable (and strange) Pablo Picasso gouache on paper drawing of a young boy—a young Picasso, maybe?—with his pants down. (Makes sense.) The latter study came to mind when I saw, at Richard Gray, a tender 1951 Lucian Freud sketch of Francis Bacon with his flies undone. (A work as unexpected as the 1927 wooden sculpture of a worker by Alexander Calder at Galerie Michael Haas.)

Alexander Calder at Galerie Michael HassGenitalia abounded at Art Basel this year, and I wasn’t the only one to notice. Even Kim Gordon’s Pussy Galore (2009) at 303 Gallery took on new meaning within the somatic din. There was a noticeable feminist slant to the bodily focus, too. In Jana Euler’s Under this Perspective, 1 (2015) at Galerie Neu, a body is compressed to a penis (complete with a little head for an eye) and a pair of feet, while Judith Bernstein’s suite of peen-filled works at Karma International in Features, included works with titles like Jackoff Flag and Crying Cuntface.

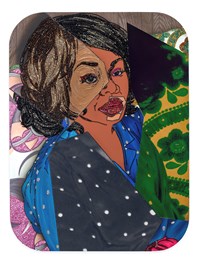

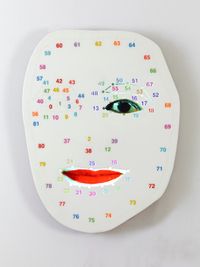

Judith Bernstein at Karma International. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art BaselThe female bodies which appear in the work of Matisse, Schiele, Klimt et al were countered in the Features section, where a number of feminist practices were presented to great effect. There was the excellent Ketty La Rocca presentation at Galerie Kadel Willborn, and Carrie Mae Weems at Jack Shainman. Weems explored the role of the female body in art history through images paired with captions including: “IT WAS CLEAR I WAS NOT MANET’S TYPE. PICASSO—WHO HAD A WAY WITH WOMEN—ONLY USED ME & DUCHAMP NEVER EVEN CONSIDERED ME.” These statements found further resonance in Galerie Barbara Thumm’s solo focus on Teresa Burga, whose work has, since the 1960s, engaged with the way the body—and more specifically, the female body—has entered into processes that, quoting the gallery, “seek to standardize the subject.”

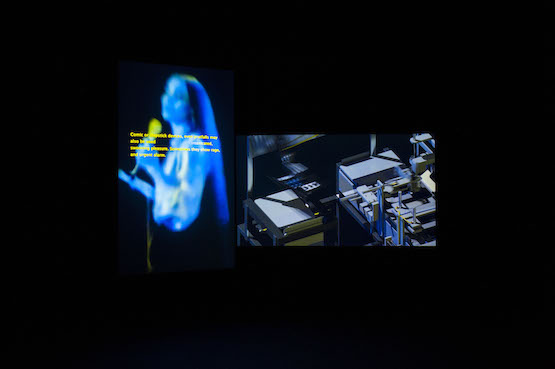

Carrie Mae Weems at Jack Shainman. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art BaselThis idea of subject standardisation was encapsulated to full effect in Elizabeth Price’s Unlimited work: the two-screen video installation K (2015), in which Price presents the story of professional mourners known as “The Krystals.” These male and female performers, rendered from archival footage, move to a soundtrack pregnant with affect; their movements are edited alongside footage depicting the mechanical process of producing pantyhose. Thinking back to Burga, the work articulates the “standardization” that occurs when bodies, capable of profound feeling and expression, are absorbed into machine processes—an interesting premise in the context of Art Basel, itself a standardising space.

Elizabeth Price, K, 2015. © Art Basel But there is a hope in Price’s work, as expressed in reference to the sun’s illuminating light, and the notion that we can all make our own illuminations. Price presents man and woman as equal, too—in this work, we are all “Krystals,” each capable of absorbing and reflecting a collective loss. This highlights another curious aspect to the 46th Art Basel. Despite all the tits and ass, the fair did not invoke the orgy of Andreas Slominski’s Erotic Vol. 63281 (2011) at Galerie Bärbel Grasslin, in which a “SPECIAL PRIVATE VIEW, GALLERY VERNISSAGE” looks more like a swingers party than an exhibition opening.

Rather, the subtext of the bodily focus was perhaps best encapsulated by Leigh Ledare’s titillating-yet-fraught study of his ex-wife, Meghan Ledare-Fedderly, in Double Bind (2010/2012): a collection of photographs Ledare took while staying in a cabin with his ex—the same cabin she would later stay with her current partner, whose images are also used in the installation. The juxtaposition of gazes—of the ex and the current lover—provided a meta-view of platonic and erotic love, further complicated by the gaze of the outside observer.

Such a triangulation was articulated in clear terms in David Shrigley’s own Unlimited offering—Life Model: a three-metre high sculpture of a naked male figure positioned in the centre of a space set up as a life-drawing studio open to all visitors.

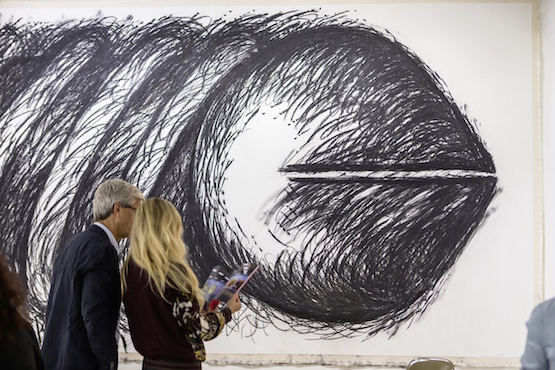

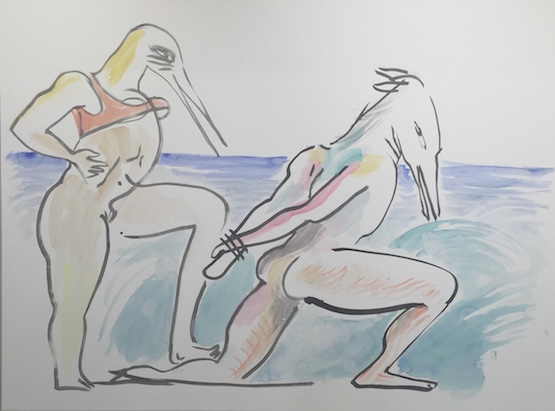

David Shrigley, Life Model, 2012, at Stephen Friedman Gallery. Image courtesy Art Basel. © Art Basel Relation, in this sense, came to stand for much more this year than the coupling in Louise Bourgeois’s Couple (2009) at Richard Gray, in which an erect member emerging from the male form is pointed straight at a pregnant woman. It became more than the perversion of Tobias Rehberger’s ongoing installation series in which pornographic scenes are presented as pixelated mosaics at neugerriemschneider. In some ways, it was encapsulated in Camille Henrot’s unexpected series of gorgeous paintings taken from the Tropics of Love series at Galerie Kamel Mennour, in which bodies with animal heads engage in light bondage.

Camille Henrot at Galerie Kamel Mennour, Art Basel 2015The sense of ‘coming together’ reached a pinnacle in the presentation of Ulay works at Features, in which his face is juxtaposed against that of a woman, Joe Bradley’s Hermaphrodite at Mitchell-Innes & Nash, and Zoe Leonard’s Pin Up No. 1 (1995/1997) at Gallery Gisela Capitain: an image of a bearded lady reclining on a bed with red sheets. These works recalled Wu Tsang’s sensitive video installation Damelo Todo // Odot Olemad (2010-11/2014) at Unlimited. In the piece, based on a short story by Raquel Gutiérrez and on Tsang’s documentary chronicling the world of Silver Platter titled Wildness, we watch as Teodulo Mejia performs in drag on a front facing screen. Behind this, on a screen facing the back wall, we are granted a view into the dressing room of the Silver Platter, where bodies are transformed, and even transcended through sheer will.

This brings us back to the Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and the philosophies it espouses. On the night of the Unlimited opening, someone pointed out: “Love is a big theme this year”—a reference to an exhibition at the excellent non-profit space SALTS titled What’s Love Gotta Do With It, held concurrent to the fair, in which curators Samuel Leuenberger and Elise Lammer invited artist couples to collaborate. What’s Love Gotta Do With It is an exploration of the potential inherent in the intimate act of collaboration: when bodies come together so as to produce a third space created out of pure, honest, conflicted, and—at times—confused relation in which two does not become one, but more and/or less.

Indeed, when asking Petrit Halilaj and Alvaro Urbano what love has to do with it, they replied, “everything.” (The Museum of Broken Relationships, perfectly installed at the Historisches Museum Basel, made this abundantly clear with a collection of objects and texts that articulated just how powerful an impression love can make.)

In the year Marc Spiegler openly admitted that the line between art and finance is becoming increasingly blurred, it seems fitting that the blurring boundaries between bodies occurred both within and without the fair. (There was Gauguin and Dumas at the Beyeler Foundation, too, which included Gauguin’s hauntingly titled work: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?) As Lammer noted on the SALTS exhibition, the reason behind conceiving a show that considers love and collaboration during Art Basel was to consider our interactions beyond the measure of a transaction. This is something DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY also considered by placing a free kitchen right outside of Art Basel’s halls. Maybe that was the difference.—[O]