Amna Naqvi

Amna Naqvi. Photo credit: AAN Foundation & Sakshi Verma Photography.

Amna Naqvi. Photo credit: AAN Foundation & Sakshi Verma Photography.

Amna Naqvi is a collector, philanthropist and gallerist who lives in Hong Kong.

She and her husband Ali Naqvi recently set up the AAN Foundation to further their ability to support, exhibit and disseminate information about contemporary and modern Asian art, with a focus on Pakistan. The AAN Foundation has plans to make their collection of over 800 works available to the public.

SAAmna, thank you for speaking with Ocula. Please tell me how and why the AAN Foundation came about.

ANThe focus of philanthropy and patronage in the developing world is mostly towards health, education and disaster relief. We had been supporting these initiatives, but almost ten years ago we realised that along with these we should support the arts, as it was such a huge part of our lives. Culture defines who we are, and if that is not shared, disseminated and hence preserved, it can be lost. Art and culture are susceptible to the rampant global homogenisation that is occurring today, and we felt that there were ideas, philosophies, voices and opinions that needed to be discovered and explored.

Many of the projects we initially supported were need based. One such project was Authority as Approximation by Shahzia Sikander, which Hong Kong art space Para Site wanted to undertake but did not have the funds to do so. After being approached, we discussed it, and decided to support it, as we liked the project's concept. It included a Pakistani artist and was happening in the city we lived in.

Once the parameters were broadly defined, we started receiving a lot of proposals that led to us support a number of projects, including: Acconci Studio + Ai Weiwei: A Collaborative Project at Para Site in 2010; The Rising Tide: New Directions of Art from Pakistan (1990–2010), a survey show at the Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi, in 2010; Lines of Control at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, 2012; Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi at the Asia Society Museum, New York, 2012; and Song Dong: 36 Calendars, an Asia Art Archive project that took place in Hong Kong in 2013.

A significant part of the AAN Foundation's aim is to provide support at the very initial/conceptual stages of projects that have the potential to become platforms for further strengthening the artistic space in their own areas and geographies. This focus has provided seed funding for the Faiz Foundation Trust, the Lahore Literary Festival, and the Lahore Biennale Foundation, among others. It has also supported institutions such as Asia Art Archive and Para Site art space in Hong Kong over the past ten years.

The role of the foundation will be to give support to a wide range of artforms with a particular focus on visual arts from Pakistan, in a sustainable and institutionalised manner. This includes offering platforms and support for exhibitions, private as well as public art projects, and publications. Geographically, the foundation is focused on enabling and encouraging art from Pakistan, South Asia and the Asia Pacific, locally as well as globally.

SAWhat lead you to set up the Foundation at this point in time?

ANInitially, we had been supporting projects very organically. And usually projects initiated by larger institutions, and by curators and directors who knew us personally. If we liked the idea or the project, we would get behind it. It was a more ad hoc process, as these things tend to be in the beginning. It came to a point where we felt we needed to formalise the process and work with institutions and projects on a longer-term basis. We thought that with a foundation in place, we could enable ideas, projects, spaces, and funds in a more sustainable manner.

SATell us about the art in the collection of the AAN Foundation.

ANWhat began with an impulsive purchase of an artwork in 1994, has led to a collection of over 800 works by over a 100 artists. The AAN Collection is composed of classical, modern, and contemporary art, including 3rd-century Gandhara sculptures, miniatures from the Mughal and Lucknow schools, and historical objects from the Tipu Sultan collection. There are works by Pakistani modernists, including Sadequain, Ismail Gulgee, Jamil Naqsh, Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Anna Molka Ahmed, and Ahmed Pervez. We also have works by Indian Moderns from the Progressive School, such as F.N. Souza, S.H. Raza and M.F. Hussain.

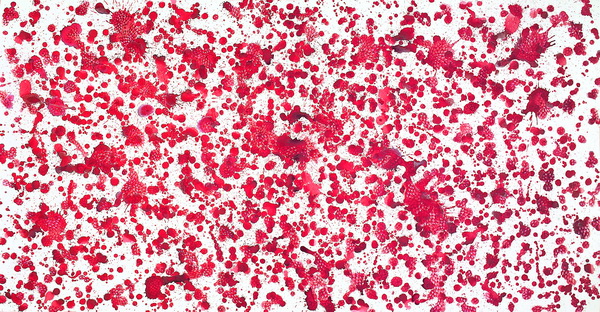

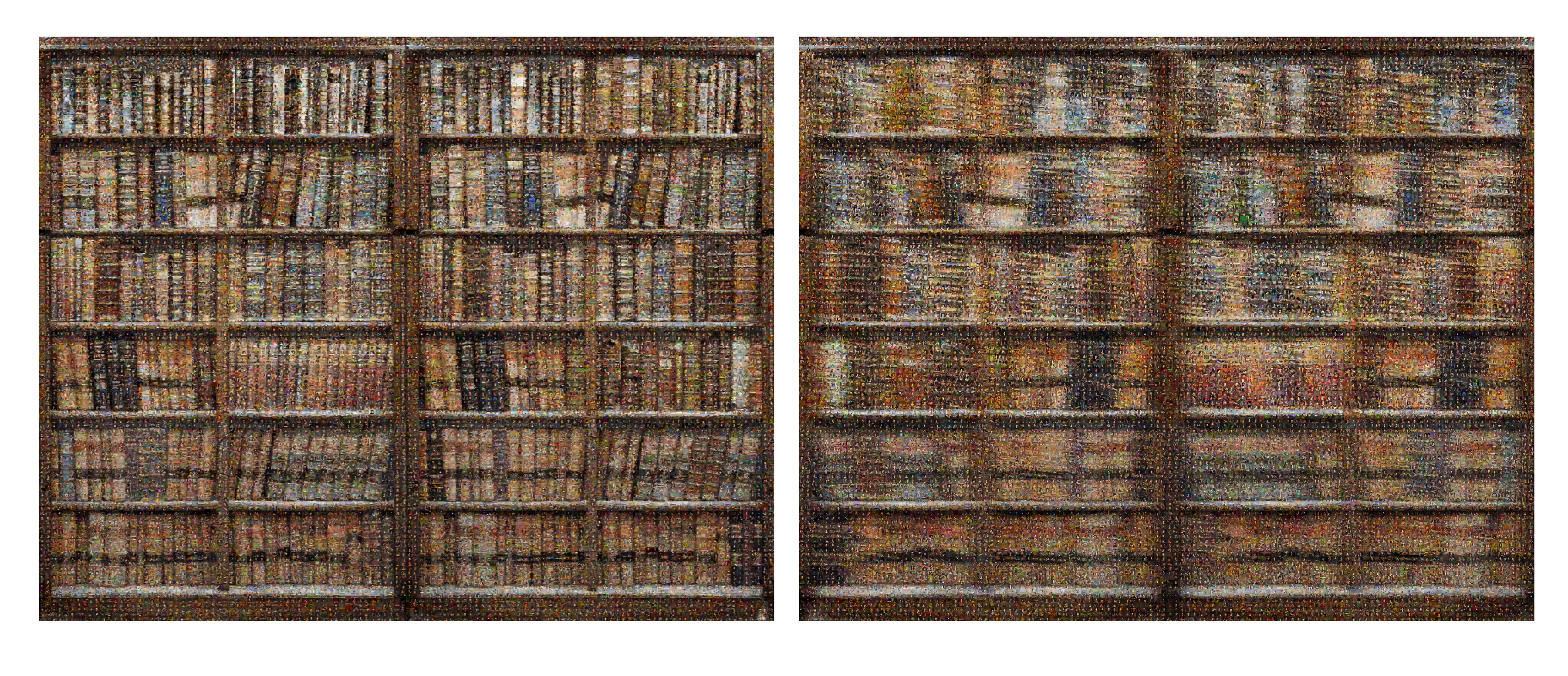

The heart of the collection is Pakistani contemporary art, though there are nods to contemporary art from China, Japan, India, Korea, Bangladesh, Taiwan and Indonesia. Among the Pakistani artists there are in-depth collections of work by Rashid Rana, Imran Qureshi, Shahzia Sikander, Khadim Ali, Aisha Khalid, Naiza Khan, Bani Abidi and Faiza Butt, to name a few.

The collection has been shared with a broader audience through extensive loans of the works to museums, public and private exhibitions/projects, and through publications including books and periodicals. Over the last 10 years works from the collection have been on loan to over 40 museums and public art spaces, including: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Asia Society Museum, New York; the Sharjah Biennial; the Venice Biennale; the Singapore Art Museum; and the Mohatta Palace Museum, Karachi.

The collection is composed of various media including sculpture, work on paper and canvas, photographic work, video installation, light box, and other new media. Until 2015, the largest work was Desperately Seeking Paradise (2010–11), by Rashid Rana; a cubic sculpture that is approximately 3 metres in height. Shahzia Sikander's animation Parallax (2013), is now the largest and most challenging work in the collection, at 3.5 x 20 metres. The smallest works are contemporary miniature portraits by Ahsan Jamal. Another interesting work is Aisha Khalid's Page to Page (2007), which is a re-creation of the Mughal album.

Twenty paintings have been bound in the form of a codex and can be viewed as historic miniature paintings were originally meant to be enjoyed—by holding the album in one's hands. The process of perusal is unique as the paintings are not imprisoned by glass and the viewer can appreciate the fine details in the painting. Other works include a 7.5 metre-long untitled calligraphic artwork on jute fabric by the modern artist Sadequain, and an installation by Risham Syed, History as Representation 2, 2014, composed of an antique camera stand, a vintage fur shawl and contemporary painting.

SAHow do you ultimately see the works being presented? And where?

ANAs the collection's profile increases, we get asked this question more frequently. We have been grappling with these thoughts and questions ourselves. There has been a great deal of talk of housing the collection in a permanent space (museum). While this is an obvious solution, we are not sure whether, in the current age of geographic and technological mobility, a permanent museum alone is the best way to broadly share the collection.

In addition to loaning works in the collection to institutions, the Google Cultural Institute has become another vehicle for sharing the artworks. Google Cultural Institute Pakistan was launched last year and the AAN Collection was selected as one of its six partners. The other institutions selected are mostly repositories of historical objects or keepers of historical sites, so the AAN Collection is the only contemporary and modern art collection to be part of the initial launch. As a way of viewing art, it does not replace or diminish the process of standing in front of an actual object or work of art, but, in terms of access, it is incomparable.

SAPlease tell me about bringing the Asia Society's Shahzia Sikander show Apparatus of Power to Hong Kong.

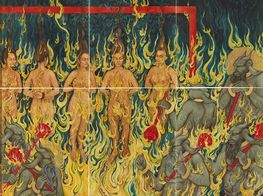

ANTo define Shahzia Sikander's practice is a colossal task, as it not only spans the period of her artmaking, but rather it crosses and transverses both historical and geographical boundaries. The miniature tradition in which she has honed her skill is almost four centuries old, while the animations and paintings she creates, drawing upon this ability, are contemporary in form and idea.

The narrative and images drawn upon are from historical Lahore and Laos, from contemporary Sharjah and New York, and include deities, animal motifs, fantastical creatures, portraits of royalty, maritime trade routes, ideas about imperialism, de-constructed calligraphy, shapes such as the circle and rectangle, poetry, oil wells dressed as Christmas trees, and objects as mundane as soccer balls. As varied as the subjects are, they are tied with a certain singularity to a powerful narrative Sikander wants to convey.

We were so pleased that the Apparatus of Power was shown at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center, a space that is steeped in the history of this city and yet is contemporary in its manifestation much like Sikander's practice. So bringing this exhibition to Hong Kong made perfect sense.

SABecause of the security situation in Pakistan, the country does not see many international art visitors. Please tell us about the art scene in Lahore and Karachi.

ANPakistan is a 70-year-old nation with a 3000-year-old past. Its heritage begins in the cities of the Indus Valley civilisation and continues more recently at the National College of Arts (NCA), with the neo-miniaturist school subverting tradition to create contemporary works of art. The last two decades have been particularly challenging for the country but the situation has fuelled the creative energies of artists, both in the country as well as in the diaspora. As a result, Pakistani art is feted internationally and shown in museums, biennales and public institutions around the world.

In the last five years, a strong and vibrant local art scene has emerged due to the confluence of a number of positive factors. At the forefront is the deepening as well as broadening of art institutions' curricula. The oldest art school is the National College of Arts (NCA)—formerly the Mayo school of Arts—and it was set up by the British next to the Lahore Museum in 1875. The first principal was Sir Lockwood Kipling, the father of Rudyard Kipling.

He was also the first curator of the Lahore Museum. The NCA has been at the forefront of the art narrative in Pakistan for the last seventy years or so. This is now complemented by a more robust and broader art education scene, with several private and public institutions providing tertiary art education in major, as well as in the smaller, cities.

Development of a stronger gallery infrastructure in the last ten years in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad has complemented these burgeoning art institutions. Karachi is now host to a quasi-art district in the seaside neighborhood of Clifton. Interesting public art projects, artist collectives, independent curators, and plans of possible biennials are fuelling this vibrant art scene. Above all, an increasingly wider local audience engagement, along with a growing base of younger collectors, is feeding this robust return to arts and culture for the first time since the late 1970s, when the dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq led to the discouragement of artistic expression and activity.

SAWhat are young Pakistani artists today interested in portraying and how?

ANIn the last three years I have seen a change in the stories that Pakistani artists are narrating. They are moving away from political and other fractious issues to deal with subjects of development, race, consumerism, materialism, urban development. Works are also becoming increasingly conceptual. Yet there are artists still subverting and experimenting with tradition. The means to this end could be the deconstruction of calligraphy or subversion of the miniature format in a new manner. The exploration continues with renewed zeal.

SAYou have been in Hong Kong for 14 years. How has the market for contemporary art and the spaces for showing art developed over this time?

ANWhen I moved to Hong Kong there was literally a handful of galleries on Hollywood Road and a few art dealers showing the work of Chinese contemporary artists, with the auction houses holding their Spring and Autumn shows. Ten years on and the art scene here is robust, with dozens of galleries showing works of international artists. Art fairs like Art Basel and its satellite fairs, as well as strong art programs by not-for-profit organisations and art spaces, further cement Hong Kong's place as the Asian art hub.

SAHow has your time in Hong Kong influenced your outlook on collecting and philanthropy?

ANHong Kong gave us the ability to collect challenging work. I met Hong Kong collectors who advised me never to give up on a work that could not fit in my home, as I would regret not having it later. And never to shy away from difficult media. I think Hong Kong gave us the confidence to collect what we liked and not demur if the installation or the maintenance was a challenge. Now I enjoy juxtaposing a traditional miniature with a contemporary one or a 3rd-century Eros with a photograph of Superman.

Hong Kong also led me to art philanthropy. I saw it happening around me with other individuals supporting the arts, and I was inspired by their passion, commitment and zeal.

SAAs a relatively new area of collecting, do you think collectors of contemporary Asian art have a responsibility to make work available to the general public and to offer opportunities for education?

ANIf you are not going to share the stories, they will gradually disappear from general purview. There needs to be a continuous engagement, a constant sharing of ideas. That is why it is important to keep showing the works in exhibitions, in publications and online, so as to provide opportunity for discourse, discussion and education.

SAWhat characteristic makes someone a great collector?

ANDisruption.

The best artists are disruptive by their very nature and if collectors are not bold, they will never collect challenging works. Collectors have to move out of their comfort zones, they should be challenged every which way by the work of art.

SAWhy collect?

ANI see us as collectors of stories, histories and narratives. Stories need to be told and shared, either in the form of a museum, an online platform, a program, an exhibition, a publication or a space. Or all of the above, as time will tell.

Someone has to collect the stories. I am glad we do. —[O]