A Monumental Show in Athens Raises Questions about Scale

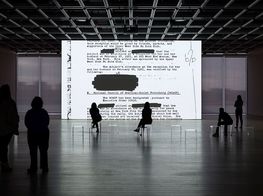

Glenn Ligon, Waiting for the Barbarians (2021) (detail). Neon. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by NEON. Exhibition view: Portals, Hellenic Parliament + NEON at the former Public Tobacco Factory, Athens (11 June–31 December 2021). Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery. Photo: © Natalia Tsoukala. Courtesy NEON.

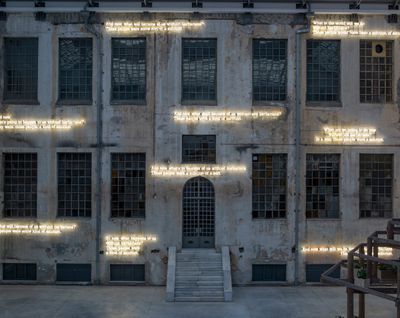

Covering one wall in the former Public Tobacco Factory of Athens is Cities (adjusted to fit) (2004/2005/2015), a photograph on adhesive wall material by Louise Lawler that captures the inside of the 2004 exhibition Contemporary: Inaugural Installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The top edge of a photo documenting an urban ruin saved by Gordon Matta-Clark takes up the entire bottom section of the image. Beyond that, photographs by Thomas Struth and David Goldblatt line one wall, of densely built commercial centres and cities under construction from Paris to apartheid South Africa.

In Lawler's capture, different city dynamics are frozen in the frozen time of museums and art spaces: structures that affect the future of the neighbourhoods where they are located. Lawler's selective framing invites not only a reconsideration of the ever-changing dynamics of urban space, but also the way the context of an image's presentation affects its reception.

The clue is in the title, adjusted to fit. Scaled up or down to work with different walls, exhibition spaces, artistic and curatorial concepts, Lawler's series changes dimensions according to the site, to match proportions of a given wall at any scale determined by the exhibitor, possibly distorting the initial image in the process of adjustment.

On view in Portals at NEON, Athens (11 June–31 December 2021), Lawler's photo seems to stand as a metaphor for the exhibition in which it is located, blown up to monumental scale to match the vast spaces of a historic industrial space, in a show where monumentality seems to rule over ideas.

NEON is a non-profit arts organisation founded in 2013 by Greek collector Dimitris Daskalopoulos with the goal of bringing contemporary art to the public. Organised in collaboration with the Hellenic Parliament on the bicentenary of Greece's War of Independence, Portals marks the renovation of the former Public Tobacco Factory, funded and supervised by NEON, to be used as a cultural venue by the Greek state.

The curators Elina Kountouri, NEON's Managing Director, and Madeleine Grynsztejn, Pritzker Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, present a selection of works from 59 international and Greek artists, among them Steve McQueen and Apostolos Georgiou, 15 of which are new commissions.

Their chosen title, Portals, refers to the current moment as 'a gateway between one world and the next,' per novelist Arundhati Roy's 2020 Financial Times article that considers ways out of this pandemic.

The abundance of monumental works by well-known artists makes more fragile, low-key pieces easier to relate to...

'We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us,' Roy suggests, 'Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world.'

It's not clear which way the curators have chosen to go in a show that seems too eager to compete with the impressive 6,500-metre-square space of this emblematic venue. The result is a lifeless curation of artworks, many of them monumental, that largely fails at capturing the zeitgeist of the pandemic era.

An a-temporal aura abounds. Descriptive connections between different works—either under generic section themes like 'Movement' and 'Connection'—creates the feeling of a permanent museum collection rather than a vital exploration of an uncertain present.

In the 'Attic' section, installations are as fragile as the connections they might share in common beyond their formal elements. Be it Nikos Alexiou's Fear (2003), a labyrinth of paper houses; Vlassis Caniaris's Child Desk (1972), a cardboard microcosm of an immigrant home in Germany during the 1960s and early 1970s; or Alexandros Tzannis' subtle ceramic, metallic, and neon micro-sculptures seemingly growing out of the building's walls and ceilings that compose Interference, Noise and Message (The Parasite Series) (2020–2021).

Robert Gober's ready to collapse Pitched Crib (1987) is still haunting no matter how many times you see it, but it seems to suffocate under a section organised too literally around the theme of 'Home', alongside Do Ho Suh's fragile 348 West 22nd St., Apt. A & Corridor, New York, NY 10011 (2000–2001), an exact replica of his apartment in New York made from translucent pink and blue nylon.

Issues with scale surface across the show. As Jannis Kounellis said of his installation Untitled (1988), composed of metal beams pressing onto stones and sacks of pyrite, the weight of the work 'determines and polarizes the space'.

The same goes for Kutluğ Ataman's major installation Küba (2004), with rows of televisions positioned in front of a chair each filling a massive hall. Every screen presents interviews with 40 inhabitants, mainly former refugees, of the eponymous region of Istanbul: a community whose poverty is a force for unity among them.

These two very bold testaments on labour, class, and globalisation leave little room for more recent, conceptual studies into these same conditions. Like Anastasia Douka's Anger organizes (2021), a composition of aluminium tubes that supposedly mutates energy constantly, in conversation with the building's architecture and utopian experiments of early thermodynamics.

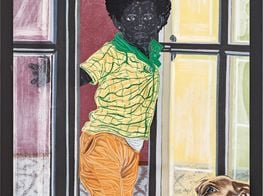

The abundance of monumental works makes more fragile, low-key pieces easier to relate to, like Billie Zangewa's intimate silk tapestries depicting herself and her son at home (Back to Black, 2015; Temporary Reprieve, 2017) or Toyin Ojih Odutola's A Solitary pursuit (2017–2018), a portrait of a Black woman driving a pink Cadillac in the desert that breezily invites a reimagination of past and future.

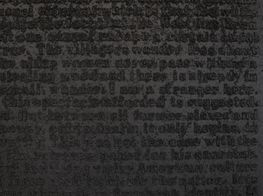

But for the most part, personal stories are repressed by grand narratives and grand gestures, such as the addition of 'Liberty 2021' written on the wall in Greek as a reference to the bicentennial of Greek Independence: an unfortunate addition to Felix Gonzalez-Torres' seminal installation Untitled (1989).

Defined by a list of personal and historical incidents and dates—among them, 'Black Monday 1987' and 'Berlin Wall 1989'—the work can be altered by its owner through the removal and/or addition of phrases and dates each time it is manifested.

A moment of respite comes in the central atrium, a vast light-filled space crowned by a glass roof, where a group of works hold court, among them a neon light installation by Glenn Ligon that consists of nine English translations of the final two lines of C. P. Cavafy's 1904 poem 'Waiting for the Barbarians': 'Now what's going to happen to us without barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution.'

Here, the site-specific commission by Danh Võ, Untitled (2021), constitutes a wooden pavilion with a pyramid roof frame filled with freshly grown nasturtiums, once cherished for their shield-like shape. The plant's botanical name, Tropaeolum Majus, derives from its armlike branches reminiscent of the tropaeum (Greek: tropaion).

Reflecting Võ's ever-growing interest in gardening, having spent recent years at his farm in rural Germany, this is a rare space for pause. Yet, a resonant sensuality is lost in the rest of this garrulous 'gardening with sculptures' installation.

In what seems like a study on the endurance of cultural codes through history, stacked tree trunks composing a dismantled wooden pavilion is accompanied by a 17th-century sculpture of the Madonna and Child and a driftwood rendition of Christ crucified laid out on white Carrara marble, into which Võ has carved the outline of a male torso.

Võ's installation, unfortunately, points to the issues of staging a grandiose show like this in Athens right now, as the local art scene struggles to survive. Particularly given NEON's stated mission to promote contemporary art in the local context and its unofficial substitution for the lack of education and state policy for contemporary art in Greece, where the emphasis is on the preservation of ancient heritage.

That said, another site-specific commission does succeed in creating a threshold in relation to this exhibition's stated intentions to connect with the globalised context of the pandemic.

Adrián Villar Rojas' The End of Imagination (2021), one of the few video installations in the show, departs from Covid-19's outbreak. The artist and his team compiled 16,000 hours of real-time footage from webcams around the world, working eight hours daily for 12 months. In the footage, something surprising emerges. Beyond deserted cities and urban isolation, animals are seen in game reserves, zoos, conservation parks, and aquariums; continuing their daily rituals as if nothing has happened.

In contrast to The Theater of Disappearance (2017), the artist's costly site-specific installation commissioned by NEON four years ago to alter the indoor and outdoor space of the National Observatory of Athens by temporarily planting 46,000 different plants, The End of Imagination is an acute view on life at its most intimate.

Beyond how to live in a crisis, the work says a lot about art and exhibition-making within the evolving ecologies of art, in a show that can sometimes feel like a waste of resources. Especially when thinking about the contextual specifities that are so often lost in international exhibitions of this scale.—[O]