Lynn Hershman Leeson: 'I had to wait 30 years for the millennials to be born'

Lynn Hershman Leeson. Photo: Henny Garfunkel.

Lynn Hershman Leeson. Photo: Henny Garfunkel.

While virtual reality, augmented reality, and NFTs have edged contemporary art towards new technologies in recent years, Lynn Hershman Leeson's practice has relished in the digital frontiers for over five decades.

The San Francisco-based artist's wide array of installations, performances, videos, sculptures, photographs, and works on paper have addressed the complicated relationship between humans and their inventions, as well as the constraints and biases that women are forced to contend with in modern society.

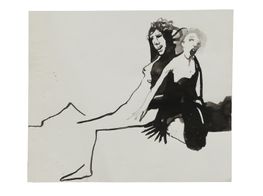

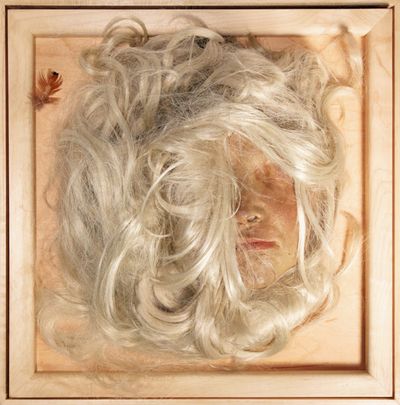

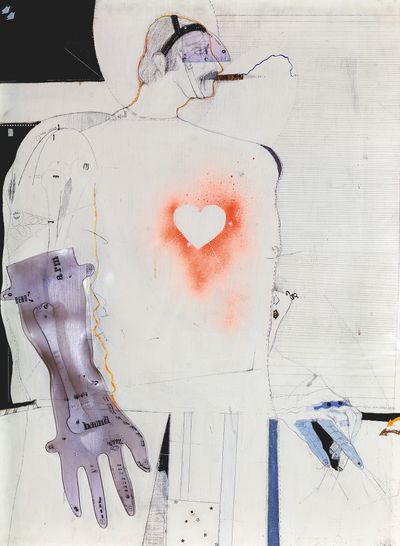

Born and raised in Cleveland, Hershman Leeson relocated to the Bay Area in the 1960s to pursue an MFA degree from San Francisco State University. Drawings and collages from the early years captured both the feminist inclinations of the era and a budding interest in cyborgs, a term coined earlier that decade. Many of these images depict female subjects donning X-ray suits that reveal their anatomies, commenting on the persistent policing of women's bodies.

I try to live in the present and notice what is going on. Many people live in the past. It's as simple as that.

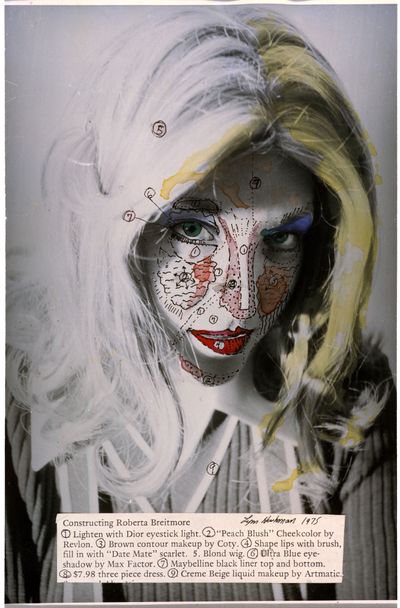

This soon gave way to multimedia and performance works that engaged with viewers in ways seldom or, in many cases, never before seen. One of the artist's most enduring projects revolved around an alter ego named Roberta Breitmore, who interacted with unwitting individuals in real-life situations that mirrored the lives of a new generation of young women in the 1970s.

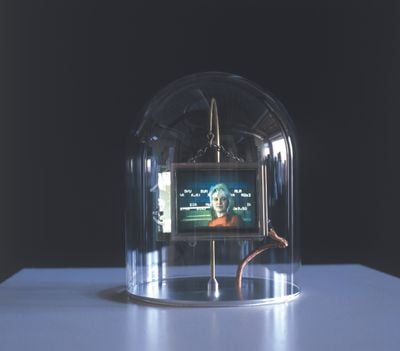

Other works, such as Lorna (1984) and Deep Contact (1984–1989) utilised mechanisms like surveillance cameras and LaserDisc technology to offer poignant statements about contemporary society's voyeuristic tendencies.

Though her CV is packed with decades of experience exhibiting works at institutions around the world, the artist was somewhat isolated due to the lack of peers working in the cross sections between art and technology.

Her installations and videos often forecasted technological trends that unfolded later on in her life—the advent of reality television for one, or the boundless consumption of information through digital devices.

It was not until recent years that Hershman Leeson's practice truly met its moment, appearing in shows that have positioned her as a figure who laid the groundworks for subsequent generations of artists, such as Morehshin Allahyari, Simon Fujiwara, Sondra Perry, and Martine Syms, with whom she exhibited at The Shed for Manual Override (13 November 2019–12 January 2020).

This summer, the New Museum unveiled Twisted, Leeson's first, and very long overdue solo exhibition in New York City (30 June–3 October 2021). That distinction, coming on the artist's eightieth birthday, reflects the significant amount of time that it has taken for the public to catch up with her pioneering practice.

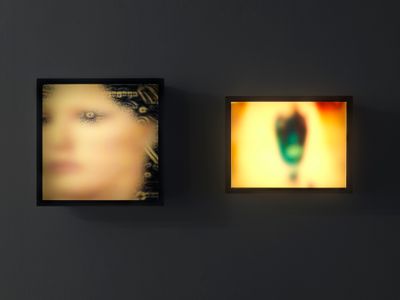

Curated by Margot Norton and accompanied by a new publication, the exhibition offers samplings from many of Leeson's series from the 1960s to the present day, as a way of tracing her ongoing interests in genome and life creation.

On the occasion of this landmark show, the artist shares the inspirations behind many of her most notable projects, her experiences working in still largely uncharted territories, and the production process behind her latest installation Twisted Gravity (2020), which was originally created for the 13th Gwangju Biennale (1 April–9 May 2021) and is currently on view within the New Museum presentation.

VCThe exhibition at the New Museum includes works that were made from the 1960s up to the present day. Are there overarching themes that connect your earlier and later works?

LHLIt is a fraction of my practice, but it is an overview of a certain element of my practice that deals with DNA. They are all about the double helix, the creation of life—synthetic, real, fictional, altered, and made at the micro biological level—and antibodies. They are also about extinction.

Quite a few of the most important works are not included in this exhibition, but it should be noted that this show is not a retrospective. It is a survey of one phase of my work, which is the idea of cyborgs.

In the exhibition, the most important works are the 'Breathing Machines' (1965–1967), 'Roberta Breitmore' (1973–1978), 'CybeRoberta' (1995–1998), Room #8, The Infinity Engine (both 2018), and of course the 'Electronic Diaries' (1984–1996)!

VCWhen did you start becoming interested in DNA, as well as antibodies?

LHLWhen I got sick in the sixties, I started to think about X-rays, looking internally, and reproductive technologies. You could see that in the drawings, and then [the series] about non-people—'Phantom Limbs' (1985–1987), 'Roberta (Breitmore)', and even the 'Dolly Clones'—that cross reality with virtual worlds.

I showed Lorna (1979–1983) once and then it wasn't shown for 23 years, because there was nothing that set the precedent.

But I started to think, around 2008, that programming the genome was probably the most profound thing that was happening in our generation. That's when I started to really investigate what was going on, who was doing it, what it would lead to, CRISPR, and so forth.

VCWhat have you learned as you've researched genome programming?

LHLThat identity is no longer biologically fixed, and can be manipulated and reprogrammed.

VCThe self plays a central role within your practice: sculptures created from wax moulded to your face, and videos and performances that feature you as a primary actor. Would you consider your work autobiographical or shaped by events in your life?

LHLYes. However, I am part of a cultural archetype, so I represent many people who identify with the same issues and experiences.

VCCould you expand on what you mean by 'cultural archetype'?

LHLEach culture creates a model that represents a certain issue. It is based on a lot of statistics.

VCWhat was the original impetus for 'Roberta (Breitmore)'? And how did her persona fluctuate throughout the duration of the project?

LHLI wanted to see whether it would be possible to create a fictional person that interacted with real life. A way to consider where fiction left off and reality set in.

She was a witness to, as well as a participant in, her culture. Eventually, she realised she was being victimised by the standards of time, which is why she went through an exorcism to recreate herself as victorious. She also became a multiple midway through, and the multiples also had negative experiences.

VCRoberta's last years dovetailed into the 'Water Women' series (1978–ongoing), of which there are new iterations in Twisted. What inspired that series in the beginning?

LHLThe 'Water Women' really came out of 'Roberta (Breitmore)', because I started to think about transience and evaporation, life cycles, and the fact of regeneration. The Water Woman was Roberta and it's just coming back in different iterations.

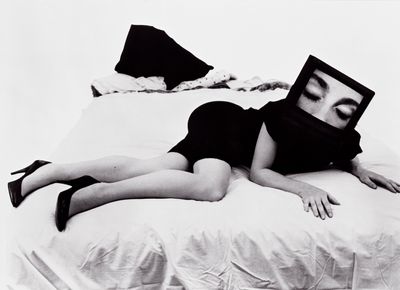

VCSurveillance and women being taken advantage of are themes that crop up often in your practice, in works such as Room of One's Own (1993) and VertiGhost (2017). Though the projects vary greatly, the subject who is being watched is always female.

LHLExactly, but women's bodies are often captured without them knowing it, which is what 'Phantom Limbs' is about as well. Women are savvier now, but surveillance often steals identity from the inside out, like through our DNA.

VCAnd what was it like to be a woman artist working in new media in the earlier chapters of your career?

LHLI was alone. No one knew what the field was or what my work was. There was no community at all. My work wasn't really shown until the Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie show in December 2014.

Most of the work in the New Museum show had never been shown, because everybody said it wasn't art. Once they started to do that and people realised that I had done things really early—and I realised that, because I didn't know that I was one of the first ones into new media until it was pointed out to me recently [laughs]—things started to shift.

You know, there's a very famous collector that went to see my work at Haus der Elektronischen Künste in Basel, which had all eight rooms of The Infinity Engine and, at the end of it, she said to me, 'Well, where's the art?'

It's still not an easy task to have people accept anything that had a scientific or technological component in it. I showed Lorna (1979–1983) once and then it wasn't shown for 23 years, because there was nothing that set the precedent. So, people didn't know how to deal with it. They didn't understand why it was art.

VCHow does it feel to see your work meeting its moment in the present, when considering how a new generation of artists and audiences are engaging with it?

LHLIt seems I had to wait 30 years for the millennials to be born. But things happen incrementally, and it is gratifying to finally show the work which has 'criminally been overlooked,' to quote Hyperallergic on this.

Every single advancement in technology had its base in warfare. I think that we have to cure that.

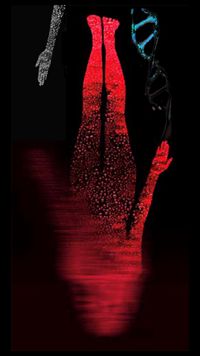

VCThe exhibition ends chronologically with Twisted Gravity (2020), which was created for the 13th Gwangju Biennale and the New Museum. Can you speak a little bit about the inspirational ideas, as well as production process, behind the installation?

LHLI had made two antibodies with Thomas Huber, who was the director of Antibody Research at the Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis at that time. It was very successful. We wanted to keep working together, and figured that a way to get rid of plastic in water was important.

Thomas found Dr. Richard Novak and his team at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, who agreed to collaborate, as they had already developed the AquaPulse system. It was using technology in creating a new form to get rid of plastic, which we desperately need, and to get rid of contaminants.

People keep saying, 'It's impossible, there's too much plastic in the ocean.' But I think that you can solve problems if you are creative and apply yourself to doing it. It was one of the best collaborations I've had.

VCThere are works that hone in on the egalitarian potentials of technology, and then others, like Seduction of a Cyborg (1994), that warn viewers about the dangers of our overreliance on digital mechanisms. Do you think that technology can do more harm than good for human society?

LHLI think it's really up to humans to use the technology that they invent and repurpose it to something productive. Most inventions—from cyborgs, which were invented 60 years ago by NASA, to every new technology including surveillance—have been developed by the military.

I think that there's an inherent strand in the DNA of these inventions that leads them to assault. Even with A.I., Alan Turing worked from the first encryptions, which were done in Nazi Germany. Every single advancement in technology had its base in warfare. I think that we have to cure that.

VC'Prescient' is a word that is often used to describe your practice, because it really is just that. Looking back, are you ever startled by how your practice, in many ways, predicted the future?

LHLI try to live in the present and notice what is going on. Many people live in the past. It's as simple as that. —[O]